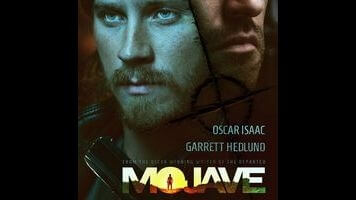

By turns inert and logorrheic, William Monahan’s pseudo-intellectual nut-scratcher Mojave is a movie of barely furnished mansions and lens flare-speckled landscapes, where sneering men say things like “I’d believe Ahab if he had two legs” and “Let’s talk about the desert… Jesus came out here” and call each other “brother” while waving guns around. Stroking his inner Norman Mailer as hard as he can, Monahan spurts out digressions on machismo, lame swipes at the film industry, and unsolicited opinions on the greats. (Byron, Rimbaud, Shakespeare, Shaw: If they had a dick and pen, Mojave has something to say about them.) Like all undisciplined exercises in writer ego, Mojave is perversely watchable, though Monahan—screenwriter of The Departed, Kingdom Of Heaven, and the remake of The Gambler, and before that a bad-boy writer for the New York Press—never manages to elevate this nonsensical cat-and-mouse thriller to demented, parodic camp on the level of Mailer’s Tough Guys Don’t Dance.

It’s not for lack of trying. Like Monahan’s debut attempt at impersonating a filmmaker, London Boulevard, Mojave is set in an artificial literary space where Hollywood burnouts cross paths with criminals, and then sit down to have long conversations about it. Here, ambiguously famous writer-director Tom (Garrett Hedlund) treks off into the Mojave Desert, only to have serial killer Jack (Oscar Isaac, with fake teeth and a weird accent) mosey up to his campfire. Introduced in a bad wig, duster coat, Baja shirt, and heavy boots (i.e., one leather bush hat short of being a member of ’80s goth rockers Fields Of The Nephilim), Jack babbles biblical and literary references until Tom whacks him upside the head and steals his lever-action rifle. Then, in a sequence of events handled in the elliptical style of an art film that ran out of money on location, Tom sleeps in a cave, accidentally kills a park ranger, and hides the evidence, only to have Jack—who witnessed the whole thing—follow him back to Los Angeles.

There, Jack gets down to business; he offs a producer, moves into his mansion, and adopts his dog and his boyfriend’s wardrobe. Less interested in blackmail than in bare-knuckled intellectual one-upmanship (“I could read when I was 2, man!”), the murdering drifter is Monahan’s latest go at his preoccupation with anti-social polymaths. (Though his New York Press days are best remembered for a gonzo piece about trying heroin, Monahan also wrote a notable article picking apart the Unabomber’s literary references.) Nowhere near as appealing as David Thewlis’ take on the same type in London Boulevard, Isaac’s bizarrely mannered performance squelches the actor’s natural charisma, turning him into a crazy-eyed vehicle for monologues and turns of phrase only a screenwriter could love. Meanwhile, Hedlund drives around the Hollywood Hills in a vintage Jaguar and broods and smokes his way through a reaction-shot-heavy James Dean impression, even though his long blonde hair, sparse goatee, and black leather jacket make him look more like Macaulay Culkin.

Not that Mojave is all that into these two characters. About half of the movie is taken up with Tom’s bad-dream-sequence-esque affair with a French actress (Louise Bourgoin) and his post-production squabbles with producer Norman (Mark Wahlberg, always dressed in a bathrobe and black Uggs) and agent Jim (Walton Goggins, never seen standing up). Full of age-old screenwriter gripes about producer notes—including, of course, an argument about an unseen film-within-the-film that’s sort of like Mojave—and loser nobodies who ask you to read their scripts, these scenes are about the closest Mojave comes to total tripe, though they do provide the movie with a decent visual gag: a producer wrapping up a business call while a couple of half-undressed prostitutes pick through Chinese food, presumably having waited long enough to order delivery.

Which raises the question: Does the movie know it’s a joke? Mojave never matches the arch knowingness of London Boulevard’s “If it wasn’t for Monica Bellucci, she’d be the most raped woman in European cinema,” but for a film that mostly blunders and bumbles along, it has more than its share of laughs, both intentional and otherwise: Wahlberg shouting “You can stick it up your ass! Right up your bum!” off a balcony; Isaac trying to make “Saving my cash for exigencies, brother” sound like something that could be said out loud, only to have to follow it up with, “I unconditionally accept service as your intention.” Both over-written (this may be the first film where “malignity” is used in dialogue) and absurdly under-conceived, this confused brawl of macho egos trips over itself from scene to scene, eventually falling flat into a meaningless finale. As with all things masturbatory, the viewer can be sure that at least one person is enjoying themselves.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.