Other People has enough insight to compensate for its self-pitying hero

“Drops Of Jupiter” makes no fewer than four or five appearances in Other People, the autobiographical first feature by writer-director Chris Kelly. The song, a soggy FM staple from midtempo balladeers Train, mostly plays during the driving scenes, rising up on the radio again and again to annoy the young man behind the wheel. Anyone who’s suffered the heavy rotation of an inescapable pop hit will get the joke. But “Drops Of Jupiter” feels personal somehow. You get the impression that the tune actually haunted Kelly, possibly during the same lousy stretch of his life he’s dramatizing here. In a way, his running soundtrack gag is a lot like Other People on a whole: It’s a little easy, a little obvious, but there’s still an undeniable specificity to it—the sense that it comes from someplace genuine.

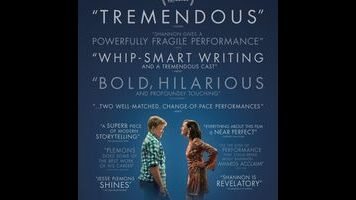

Kelly is certainly wading into some real-life trauma: the death of his mother in 2009. Jesse Plemons, chasing his sweet dolt from Fargo with a different kind of introvert, shrinks into self-consciousness to play the filmmaker’s alter ego, David, a 30-year-old comedy writer who returns to his hometown of Sacramento as his mom, Joanne (Molly Shannon), slowly succumbs to cancer. Like Amour, a film it resembles only in prologue, Other People begins with a woman’s inevitable death, before flashing back to reveal the year leading up to it. Besides removing any doubt as to where the movie is headed—a strategy that puts the audience in the same position as the characters, who never nurse illusions that Joanne might pull through—this cold open establishes the film’s sometimes awkward blend of heart and humor, as the raw grief of the family is punctured by an oblivious answering-machine message from an acquaintance blithely unaware that the person she’s called has just croaked.

It’s one of the better gags, frankly. Kelly—who (full disclosure) used to write and direct for The Onion, before decamping for Saturday Night Live—crowds the margins of his movie with sketch-comedy caricatures. But the bigger problem may be David himself, who’s a bit exhausting in his self-pity. He’s recently split with his beau back in New York—a breakup he can’t talk about with his mom, for fear that the information will burden her, or his dad (Bradley Whitford), who still refuses to acknowledge his son’s homosexuality a full decade after David came out. “I’ll have no mom, no dad, no boyfriend, no job,” David whines early on—and if Other People is willing to occasionally acknowledge his selfishness, it also adopts his tunnel vision so completely that few other characters (including David’s younger sisters, one of them played by an Apatow daughter) ever gain much dimension. At times, the film threatens to become the sitcom version of James White, that much more vivid, uncompromising Sundance alum about a self-involved son taking care of his mother during the final stages of cancer.

What keeps Kelly honest is the wealth of authentic detail he sprinkles throughout. Other People is a cancer comedy, and like such modern relatives as Harvey Pekar’s Our Cancer Year, Tom Green’s “Cancer Special,” or the similarly memoir-like 50/50, it’s at its best when getting into the nitty-gritty of coping with the disease—from an uncomfortably frank discussion of burial arrangements to the family serving as interpreter for a fading Joanne, repeating everything she croaks out in a hoarse whisper to those outside their immediate circle. And if the film isn’t as nuanced as it could be on the strange business of moving back to a small city after a decade in a much larger one, it does reserve some insight for the indeterminate boundaries of defunct long-term relationships. (Zach Woods is terrific in his three scenes as David’s accommodating ex.) Other People never quite affords its characters the same lived-in quality as their ordeal. But it steadily improves as it progresses, almost in inverse to Joanne’s deterioration, until even “Drops Of Jupiter” has taken on new meaning—the kind of context that profound experience can provide the less-than-profound stuff surrounding it. Including, yes, awful Train songs.