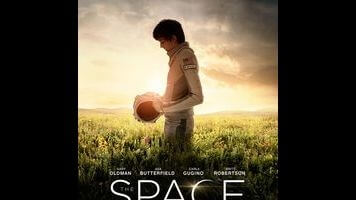

Our hearts can’t handle the industrial-strength schmaltz of The Space Between Us

Since making his big breakthrough as the plucky orphan of Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, Asa Butterfield has basically cornered the market on quivering lumps of gawky adolescent sensitivity. But he’s never played a character quite as unbearably special as Gardner Elliot, the wide-eyed emo starchild of The Space Between Us. Born on Mars to an astronaut who perished during delivery, Gardner falls to Earth on a mission, staggering under the stronger gravity of our world but taking in every mundane sight and sound with a maximum of earnest amazement. He’s a bubble-boy savant, totally immune to sarcasm, and when he meets a new person, he always asks the same question: “What’s your favorite thing about Earth?” One stranger on the bus gives him a look like it’s the stupidest fucking question he’s ever heard, and for a blissful moment, you hope against hope that maybe the film’s about to pull a Psycho and permanently switch focus to this guy. No such luck.

Did we mention that Gardner is also dying? That being on our planet is literally killing him? And that the official medical diagnosis is that his heart is just too big? Inexplicably not based on a hit YA novel, The Space Between Us is basically E.T. by way of Nicholas Sparks. It’s the kind of processed-cheese tearjerker, completely devoid of shame, that can harden even the easiest criers into heckling cynics. You want to take its lunch money or at least introduce it to better music. On top of that, it reeks of desperate post-production tinkering; the relentless flow of maudlin montage during the first act betrays a troubled production—finally in theaters, after several delays—that can’t even efficiently deliver its gallons upon gallons of schmaltz.

It takes somewhere in the neighborhood of 45 minutes for The Space Between Us to even get Gardner to Earth. The labored sci-fi setup establishes East Texas, the Mars settlement masterminded by Elon Musk-type Nathaniel Shepherd (an overacting Gary Oldman, rocking some Jeff Bridges facial hair), and the unplanned pregnancy that results in a classified colony baby. (Countless movies have recreated the NASA nerve center, but have you ever seen an ultrasound thrown up on the big screen?) Flash forward 16 years and the baby is now teenage Gardner, passing his time on the red planet in the company of a robot sidekick that seems to have acquired its personality from C-3PO and old episodes of Entourage (“I’m your homie,” the rust-bucket chirps. “Hug it out.”), while projecting a yearning desire for his dead mother only slightly less Oedipal than the one Haley Joel Osment transmitted in A.I.

Once the young K-Pax has touched down on our terra firma, he sneaks off to find the father he never knew, enlisting the help of Tulsa (Tomorrowland’s Britt Robertson), a spiky teenage crush he’s been long-distance video chatting. The love story is a gaping black hole, the chemistry nonexistent—mostly because Robertson, now in her mid-20s, comes across like a grown-up romancing a barely pubescent android. Meanwhile, Oldman’s blubbering mogul teams up with Gardner’s surrogate mother figure (Carla Gugino) to mount the most incompetent government manhunt in movie history, pausing occasionally to spout some pseudo-science about the kid’s worsening physical condition. The future-world-building is, incidentally, just as lazy: Only some self-driving cars and translucent computer monitors situate the action anywhere but now, while some of the slang (“Everyone’s always fronting”) suggests the film may actually take place sometime around 2003.

“His heart can’t handle our gravity,” Oldman at one point bellows with almost touching conviction—a line that rivals the emotion-machine climax of director Peter Chelsom’s last movie, Hector And The Search For Happiness, on the cornball camp index. Chelsom applies the middle-school-dance sentimentality with a ladle, leaning heavily on the tinkle of an overbearing score and a soundtrack of generic, cost-efficient pop cues. (You want to praise it for avoiding the most obvious needle drops, like the Smashing Pumpkins’ tender “Space Boy,” until you realize that they probably just couldn’t afford them.) For all its The Martian Jr. trappings, this is really just another story of a teenage soul too pure for this world; when the phony artifice of Las Vegas nearly kills Gardner, you half expect a floating plastic bag to rejuvenate him. Mars is apparently just the burbs with better scenery.