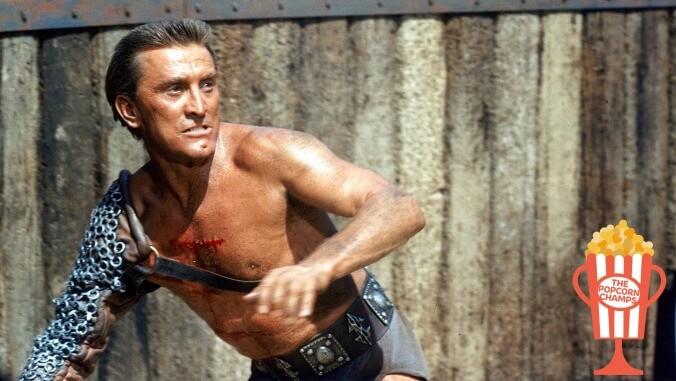

Our new column on Hollywood hits launches with Stanley Kubrick’s gladiatorial smash Spartacus

Image: Photo: Silver Screen Collection/Getty

Kirk Douglas wanted to be Judah Ben-Hur. At the time it came out, William Wyler’s Ben-Hur was the most expensive movie ever made. It was a huge, overwhelming production, cast with thousands of extras and filmed on sets bigger than anyone had ever used. And the film turned out to be a phenomenon. It was the highest-grossing movie of 1959, and it won 11 Oscars, more than any movie before it. (There still hasn’t been a single movie that won more Oscars, though a couple have tied that number.) Kirk Douglas was one of the biggest stars of the ’50s, and he wanted that title role, but it ended up going to Charlton Heston instead. So Douglas went about making his own Ben-Hur. That was the idea, anyway.

And Spartacus, which would become the highest-grossing movie of 1960, is similar to Ben-Hur in a lot of ways. Like Ben-Hur, it’s a long, majestic story of an enslaved prisoner who heroically finds his way to freedom and ends up taking on the decadent evils of the Roman Empire. But there’s a key difference. Ben-Hur is a religious movie. It’s not an out-and-out biblical story, but Jesus shows up again and again—a silent supporting player who always happens to arrive at pivotal moments. The movie’s Christianity is relatively subtle, at least for its time, but it still thrums throughout. In some ways, Ben-Hur is the culmination of a whole wave of religious epics, the pinnacle of a lineage that includes huge ’50s hits like The Ten Commandments and The Robe. Spartacus is something else. It’s a movie about class struggle.

We hear about Christianity exactly once in Spartacus, and it’s in the opening minutes of the movie. A narrator sets the stage and then never returns. Our story, he tells us, takes place “in the last century before the birth of the new faith called Christianity, which was destined to overthrow the pagan tyranny of Rome and bring about a new society.” Once that’s dealt with, nobody brings up Jesus again for the entire vast span of the 184-minute megalith. (When I decided to take on this project, I didn’t quite count on almost all the big movies of the ’60s being three hours long. If the running time of Avengers: Endgame seems a little excessive to you, just know that it’s nothing new.)

Ben-Hur is a story about a man finding personal grace, reuniting with his family after years apart and seeing the effects of an actual no-shit divine miracle. In Spartacus, the hero doesn’t learn any personal lessons, except perhaps the one about the futility of his own fight and the one about how it’s worth fighting anyway. Ben-Hur tells the story of a nobleman who’s brought low when more-powerful forces turn him into a scapegoat. Spartacus, on the other hand, tells us about a slave who’s been exploited for his entire existence, who knows no other way of being. But he also knows that he’s “not an animal,” as he howls at his captors at one point. And he ends up shaking off his exploiters and becoming a big problem for them.

All of this is political. Spartacus was a real historical figure, a Thracian slave and gladiator who helped lead an uprising against Rome in 71 BC. He was a leftist hero long before he became the subject of a movie; Karl Marx was an admirer. The novelist Howard Fast started writing Spartacus, the book that was adapted into the movie, in 1950, when he was in prison. Fast had been given a three-month sentence for contempt of Congress—he’d refused to name names when called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Fast had to self-publish Spartacus because publishing houses wouldn’t deal with convicted Communist.

And it doesn’t stop there. Dalton Trumbo, who wrote the screenplay, had also done prison time for the same reason. Trumbo was a famous victim of the blacklist, one of the Hollywood Ten. He kept writing screenplays while blacklisted, but the movies he wrote—two of which won screenwriting Oscars—weren’t crediting him by name, and he was working for way less money. Spartacus stopped that. Kirk Douglas and producer Edward Lewis decided to credit both Fast and Trumbo, and the movie is widely credited with ending the Hollywood blacklist, something that Douglas has played up ever since. The real truth might be a little murkier, since McCarthyism was already losing its grip on the nation and Trumbo’s family has generally refused to buy into the Douglas narrative. But it’s become part of Hollywood lore anyway, to the point where Bryan Cranston was nominated for an Oscar a couple of years ago for playing Trumbo in a biopic.

In any case, you can see all of this play out in the movie. Fast and Trumbo had both been full-blooded Communists, and Spartacus is a movie that absolutely drips with contempt for the ruling classes. Again and again, the movie draws contrasts. We spend about an hour watching Kirk Douglas beaten down and humiliated again and again, scrunching up his absurdly chiseled face in confusion and anguish at the cruelty of his owners. Pampered noblemen sit in steam baths and decide the fate of people who are living full and vital lives miles away. They buy and sell women just to piss each other off. Douglas and his friends are whipped, branded, and taught to kill each other with businesslike imperiousness. Spartacus and a woman who’s also a slave fall in love, but only after they’re made to mate, like cattle. Deep into the movie, as Spartacus’ rebellion is already raging, someone asks him, “Surely, you know you’re going to lose, don’t you?” And when Spartacus responds, he does it with a sense of historical perspective: “Death is the only freedom a slave knows. It’s why he’s not afraid of it. It’s why we’ll win.” Workers of the world, unite.

He doesn’t win, of course. Spartacus’ freed-slave army is betrayed by the pirates who they paid to sail them out of Italy, forced to face a far-superior Roman military force, and slaughtered on the battlefield. At the end of the movie, scores of heroic freedom-fighters are lined up and crucified, and Spartacus is made to walk down a long road, lined with his dying friends. We see a huge valley full of dead bodies, including women and kids. Spartacus dies, too—on a cross, just like his comrades. He learns that his wife and son will live free, but that freedom comes to them on a rich man’s whim, not as a result of some glorious battlefield victory. For such a huge movie, it’s a stunningly dark ending—maybe the darkest we’ll see over the entire course of this column.

Spartacus’ only victories are moral. Going to war against Spartacus, the Roman dictator Crassus, played by Laurence Olivier, says, “This campaign is not alone to kill Spartacus. It’s to kill the legend of Spartacus.” The existence of the movie proves that he failed. After being defeated, Spartacus says, “Just by fighting them, we won something. When just one man says, ‘No, I won’t,’ Rome begins to fear.” As one of his friends dies, Spartacus warns Crassus: “He’ll come back. He’ll come back, and he’ll be millions.” In the movie’s most famous moment, all of Spartacus’ comrades refuse to give him up. They all say that they’re Spartacus, even though they know they’re daring the Roman forces to execute them. And they’re all telling the truth. They’re all Spartacus. It’s not a moment of individual heroism; it’s the proletarian mass coming together and becoming the hero.

The right-wing weirdos who protested Spartacus had a point: This was a straight-up leftist movie, one that never even tried to hide its politics. They were wrong to rage against it, but they were right about what the movie was. Spartacus dressed itself as an old-fashioned biblical epic, but its story was all about worker solidarity. It romanticizes a whole class of people who don’t even need to discuss a plan with each other before they start killing the people higher than them on the social strata.

So why was a nakedly leftist movie this big of a hit? Spartacus didn’t pull down Ben-Hur’s Oscar haul. (The only major award for Spartacus was Best Supporting Actor, for Peter Ustinov’s wearily cynical gladiator trainer.) But the movie was a box office hit, grossing $60 million, or about $515 million in today’s money. It didn’t make all that money by tricking people about its politics. Those politics were well-publicized; it was a news story, for instance, when John F. Kennedy, just two weeks into his presidency, went out to see Spartacus, crossing an American Legion picket line to do it.

But I don’t think all those people bought tickets to the movie as a political act, either. They weren’t going to see Spartacus because they wanted to repudiate the McCarthy era, though it probably says something that they didn’t care whether or not they were doing that. They went to see Spartacus because Spartacus was something to see. Kirk Douglas has a lot to do with that. He gives a classic movie-star performance—a physically absurd specimen of a man projecting himself as a larger-than-life champion of righteousness and vigor. The cast of seasoned stage actors has something to do with it, too; Olivier, Ustinov, and Charles Laughton give the movie an air of prestige. And Stanley Kubrick has a lot to do with it, too.

Kubrick was a last-minute replacement on Spartacus, and he was a gamble. The director was still in his early 30s at the time. He’d only made four movies. All of them had been relatively harsh and experimental, and none of them had been hits. But one of them was the bleak 1957 World War I masterpiece Paths Of Glory, which Kubrick had made with Kirk Douglas. Douglas needed a new director after he fired Anthony Mann a week into production. The actor liked working with Kubrick, and he gave him a shot, even though Kubrick had never done anything close to that scope before.

It was a good call. Spartacus is the only thing Kubrick ever directed where he didn’t have total control, and he disowned the movie and swore off the Hollywood studio system immediately after making it, moving to England to make his films. And Spartacus is probably the only Kubrick movie that’s not immediately recognizable as a Kubrick movie; it doesn’t have his icy precision or his utter detachment from petty humanity. But you can see his mastery at work all through it.

There’s not a lot of fighting in Spartacus, considering that it’s a movie about a gladiator. There’s definitely no signature showcase action set piece, like the iconic Ben-Hur chariot race. Instead, again and again, Kubrick pulls away from action. In the first gladiator fight, we don’t see a lot of what’s happening. Kubrick doesn’t make the classic mistake of glamorizing the fights that the story regards as atrocities. Instead, we only see bits of bodies moving around, the way Spartacus himself sees them when he’s waiting to fight and die. We see it play out as reaction shots, on the faces of Spartacus and his future opponent, the towering black man whose moment of self-destructive, nonverbal rebellion will help kick off the whole story. (That actor, Woody Strode, had been one of the first black players in the NFL. He became an iconic Western character actor, and Woody from Toy Story is named after him.) We hear the sound effects of men desperately clinging to survival. And then we hear one dying, and we see the victor, hurt and winded, going right back to his slave quarters, getting ready to do it all again soon enough. That’s riveting, emotional filmmaking. It trusts its audience to follow the story through visual cues, through moments of eye contact.

But Kubrick also shows total command of spectacle, of vast forces coming together. In the movie’s one big battle scene, we see geometric formations of Roman soldiers on the move—a sight that required thousands of extras to stage. And when the armies come together, it becomes a bloody, feverish death-party. We lose all sense of where the two armies are, of who’s winning. (I love the shot of Spartacus lopping a guy’s arm off.) It’s terrible, and it’s breathtaking.

There are scenes, too, where you can see Kubrick’s viewpoint at work, aiding the story where it can. Take the scene of two rich Roman women picking the gladiators that they want to see fighting to the death. They’re there with their husbands, but they’re also clearly picking the slaves who they most want to fuck. “I feel so sorry for the poor things in all this heat,” says one. That’s not an expression of empathy; it’s a signal for them to strip down. It’s a sex/death trip almost as horrifying as anything in A Clockwork Orange.

And there’s some of that, too, in the scene where Olivier’s Crassus clearly announces his intentions on another man, a slave played by Tony Curtis. Olivier tells Curtis that preferences have nothing to do with morality: “My taste includes both snails and oysters.” And he attempts to seduce him by speechifying about how it’s pointless to even think about fighting Rome: “You must serve her. You must abase yourself before her. You must grovel at her feet. You must love her.” He’s talking about himself, too.

I’d love to know what Kubrick and Trumbo had in mind with all this. Is Olivier’s bisexuality supposed to make him more villainous? Is it a sign of Roman decadence? Or is he simply looking for one more way to enforce his power over someone else? Curtis immediately runs away and joins up with the slave rebellion. He’s a house slave, an effete poet, and Spartacus starts out by making fun of him. But he stands in solidarity anyway, and he and Spartacus come to love each other. I read that character as Fast and Trumbo declaring their own solidarity, making the point that writers and artists and entertainers can be part of the exploited underclass, too. And maybe they’re also making a statement about sexuality being no big deal, since it also seems possible that there’s something going on between Spartacus and Curtis’ character.

In a lot of ways, Spartacus fits into the grand-spectacle entertainment of its era. It’s big and long and overwhelming, sometimes thrilling and sometimes boring. (Seriously: 184 minutes, complete with overture and intermission.) But little touches like those are subversive and complicated and fascinating. They point the way forward, to the movies that Kubrick and his admirers would be making soon enough.

The contender: Of the big hit movies of 1960, the most obviously influential and masterful was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the second highest grosser of the year. But my favorite of the year’s big hits is Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, the year’s #6 movie. Jack Lemmon, admirably hammy and self-abasing, is a sputtering, nervous desk jockey at an insurance company, and he keeps lending out his apartment so that the company’s execs can bring their mistresses there. They make themselves at home in his home, and he slowly inches his way up the corporate ladder as a result. But Lemmon also falls in love with Shirley MacLaine’s elevator operator, and he eventually learns that she’s the mistress of his boss. Hijinks ensue.

Just like Spartacus, The Apartment is a story about rich assholes taking unthinking advantage of the people under them, and of the people under them finally breaking out and escaping the system. (And even more than Spartacus, The Apartment implies a whole lot of sex without ever coming out and saying it.) Unlike Spartacus, though, things don’t play out so tragically. Instead, it’s a light, joyous farce of a movie, with Lemmon mugging frantically throughout and fast-talk patter flying in all directions. The movie ended up a surprise Best Picture winner, and it’s one of those rare cases where the Academy, in retrospect, actually made the right choice.

Next time: Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins’ West Side Story uses teenage street gangs and jazz-hands sparkle to tell its story of Shakespearean tragedy.

GET A.V.CLUB RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Pop culture obsessives writing for the pop culture obsessed.