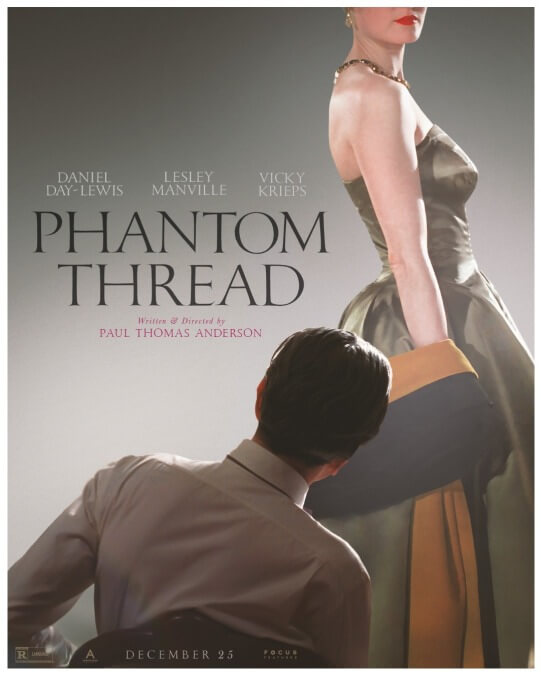

P.T. Anderson reunites with Daniel Day-Lewis for the exquisite mad love of Phantom Thread

An intimate love story set against the London fashion scene of the 1950s, Phantom Thread is as tastefully crafted as the haute couture its characters design and wear. But don’t be thrown by the immaculate embroidery. Paul Thomas Anderson, the justly revered American master who wrote and directed, is too obsessed with misfit psychologies to make a fusty costume drama. Compared to his enigmatic human puzzle The Master and his almost impossibly convoluted Thomas Pynchon detective yarn Inherent Vice, this new period piece looks straightforward and even restrained. (No one bellows “pig fuck!” or devours a bowl of marijuana.) But the mannered elegance of the filmmaking masks a perverse and finally rather moving relationship study. It’s almost a joke, or perhaps a game, one whose rules correspond to the meaning of the title: a famed fashion maestro’s habit of stitching secret messages into the linings of his garments.

Right from the title card, written in letters whose tails extend and loop to suggest folding fabric, Phantom Thread announces itself as an exquisite artisanal object. Anderson’s supreme formal control—his carefully lit and framed images, the wealth of precisely presented period detail—mirrors the obsessive care of his main character: one Reynolds Woodcock, dressmaker to the stars. Played (embodied may be the more appropriate word) by the reigning Method stalwart Daniel Day-Lewis, who won an Oscar for his performance in Anderson’s towering There Will Be Blood, Reynolds is a workaholic, a man of distinguished taste, and a creature of routine. He is also contentedly unmarried in middle age.

Loosely modeled on the British fashion designer Charles James, Reynolds lives and works in a multi-story London flat with his sister, Cyril (Lesley Manville), with whom he shares an unusual, codependent relationship; his “old so-and-so,” as he affectionately calls her, dutifully handles most of his affairs—including, it would seem, the indelicate business of dumping the women whom he welcomes briefly into his life, before growing inevitably impatient with them. One gets the sense of a cycle, and Phantom Thread begins at what appears to be the latest turning point that starts it anew. Cyril has only just removed the last hints of her brother’s latest dead romance when Reynolds, sitting down for lunch during a weekend in the country, is instantly drawn to the woman waiting on him, an immigrant named Alma (Luxembourgian actor Vicky Krieps). Their unusual meet-cute takes the form of an almost seductively excessive food order; Anderson maintains his gift for magnetically off-kilter one-on-ones.

Reynolds, as it turns out, is looking for more than a partner. He wants a model and maybe a muse, too, which Alma discovers when her first date with the confident, well-dressed stranger transforms almost imperceptively into a dress fitting. (“You have no breasts,” he tells her, shattering any pretense of polite courtship, though he means it as a compliment.) Phantom Thread often resembles a kind of relocated Gothic romance (there are faint shades of Jane Eyre), with Alma moving into the film’s equivalent of a grand manor, subjecting herself to the strict rules and eccentricities of a life within The House Of Woodcock. She has her own room, which is just one way the line between lover and employee blurs: Since Reynolds scarcely separates his work and his private life, Alma is swept into both at once. “I can stand endlessly,” she boasts, relishing her ability to match Reynolds’ tireless drive. But is there actually a man behind all that reputation, clout, and ego?

On paper, it’s a dynamic familiar enough to be called archetypal. But Anderson specializes in complicating relationships, from the complex guru/disciple bond at the center of The Master, to the unspoken frenemy pact between fascist cop and counterculture dick in Inherent Vice, to the transgressive but oddly touching big, happy porno family of Boogie Nights. In Phantom Thread, part of the fun is watching Alma, an X factor in Reynolds’ highly controlled life, upset the balance of power. She shares his attraction, but is drawn to his vulnerability, not just his confidence; “I think you are only playing strong,” she tells him on their first date. And she often refuses to indulge his quirks and demands, like the need for total silence at the breakfast table. A duet of affection and irritation, Phantom Thread teeters, too, on the edge of romantic comedy. There’s a lot of humor in its passive-aggressive tug-of-war.

In his almost royal remove, Reynolds is a far cry from the grubby baron of rage and ambition Day-Lewis played in There Will Be Blood. This new character has his own severity and short temper, and he can be cruel both accidentally and on purpose. But Day-Lewis, in a terrifically testy performance that he insists is his last (the Method must be exhausting, especially when applied to thorny tyrants), finds notes of tenderness, joy, and good humor in Reynolds—a beaming pleasure that comes poking through the character’s default superiority. Anderson, with his increased favoring of tight close-ups, is ideally suited to capturing the emotions competing for control of Day-Lewis’ features; theirs is a director-star pairing for the books. Amazingly, and crucially, he’s also found someone who can hold her own against this titanic talent: Krieps, who’s largely unknown in the States but not for long, has a warmly naturalistic force of presence that grinds productively against Day-Lewis’ meticulous control.

There’s perhaps not such a wide chasm separating the intense artist Anderson has written and the one he’s cast. Surely, too, there’s kinship between the director himself and Reynolds, a highly gifted aesthete who doesn’t care what’s fashionable in his medium. (Not to put too fine a point on it, but one scene finds him gazing through a peephole like a viewfinder, spying on a private fashion show of his work.) Anderson shot the film himself, and his 35mm cinematography has a look and texture radically different than anything else he’s made—a subtle, suggestive quality of light that went out of vogue ages ago. It pairs well with the uncharacteristic tinkle and swoon of Jonny Greenwood’s music, which possesses almost none of the sinister discordance of his previous work for Anderson. We’re a long, long way from the dick-swinging, long-take virtuosity of the director’s Scorsese-and-Kubrick-aping salad days: In the simple, refined timelessness of its technique, Phantom Thread is practically a love letter to classic aesthetic values—cinematic, sartorial, or otherwise.

This isn’t the only film this year about how damn hard it is to live with an artist, especially one that sees you as an inspiration one minute, a distraction the next. Mother!, by fellow one-time ’90s hotshot Darren Aronofsky, got there first. But Phantom Thread turns out to be a more charitable and even poignantly hopeful take on the subject. Reynolds thinks he wants an obedient mannequin, to be dressed and controlled and fit into the immaculate tapestry of his life. But it’s notable that when he first spots Alma, attraction sparking instantly, it’s during a moment of spontaneous disorder—of minor chaos, even. Perhaps he doesn’t know what he wants or needs, but maybe Alma does. By the surprising ending, these lovers have inched toward a mutual understanding, and Phantom Thread has revealed the wicked insight it’s been building toward all along. Anderson’s most diabolical trick is woven into the fabric of his style: He’s used perfectionist craft to celebrate the value of imperfection.