Paperbacks From Hell is as wild as its source material

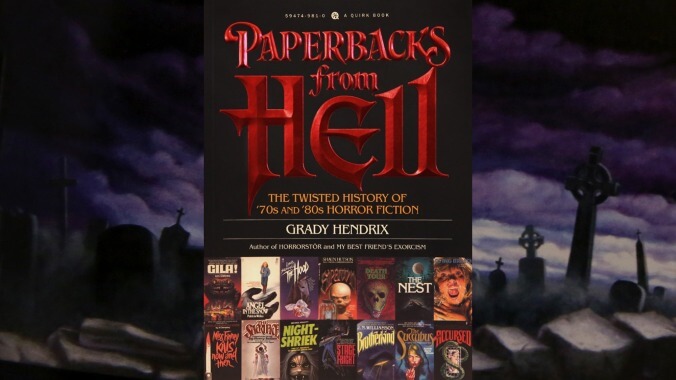

Paperbacks From Hell, the new foray into nonfiction from horror novelist Grady Hendrix, opens with an image that will be familiar to voracious readers, or pop-culture obsessives of any sort: The thrill of discovering a piece of media that you know is about to send you down a fanatical rabbit hole. In Hendrix’s case, that piece of media was a paperback novel called The Little People about S&M-obsessed Nazi dwarves (really). That discovery eventually led to this book, which weaves together social history and outrageous plot descriptions to form a portrait of the horror paperback boom of the 1970s and ’80s. Written quickly by insanely prolific authors and destined to become pulp within months of their release, these books (and their publishers) valued sensationalism and timeliness, which resulted in wild premises, wilder cover art, and lots and lots of sex.

Each chapter begins with an iconic novel like The Exorcist or The Omen before delving into their many, many spin-offs, a structure that helps put the different subgenres into context, particularly for horror movie buffs. (There’s surprisingly little overlap between horror movies and novels outside of the blockbuster hits.) Hendrix similarly puts these books into context by tying them to sociopolitical trends; the chapter on haunted-house novels is especially incisive, drawing parallels between the evolution of ghost stories and the economic anxiety of the 1970s. Another interesting observation comes in the segment on Native American curses as a horror trope, which Hendrix concludes play a role similar to the nuclear threats of apocalyptic fiction as a reflection of America’s sins.

Within each chapter, Hendrix tends to go on tangents, like in a chapter on Gothic fiction that begins with illuminating biographical detail on Anne Rice and V.C. Andrews, then pauses for a sarcastic riff on the clichéd protagonists in horror fiction before picking up again. But while Paperbacks From Hell careens deliriously between topics on a page-to-page basis, by the last chapter of the book a historical arc has emerged, taking us from the occult revival of the late ’60s to the serial-killer novels that oversaturated the market in the late ’80s and early ’90s, eventually causing the horror paperback to suffocate under the reams of paper it produced.

Hendrix’s writing is glib and sarcastic, keeping things lively even when they get a bit unfocused. Writing about killer clowns in horror fiction, he quips, “since time immemorial, humankind’s greatest natural predator has been the clown,” and he summarizes Jaws as “a novel about a stressed-out great white shark suffering from portion control issues.” While some of the trashier books get sliced into a few sentences by Hendrix’s razor wit, others, from obscure authors like Michael McDowell and Elizabeth Engstrom, receive respectful recommendations based on literary merit. And, given that cover art was as essential to a horror paperback’s success as the prose within, selected artists are given the biographical treatment, some of them for the first time. (In a bit of meta-humor, the cover of the book sports the same foil lettering and outrageous back jacket copy discussed in detail within.)

In the end, the biggest problem with Paperbacks From Hell isn’t much of a problem at all. Although the book is a quick read that could be finished in a couple of afternoons, with so many undiscovered avenues and colorful digressions to explore in this largely forgotten world, you may end up with a rather unwieldy reading list by the end. Personally, this writer can’t wait to track down a copy of J.N. Williamson’s Brotherkind, about a parapsychologist who stops a race of midget aliens from turning Earth into one giant intergalactic gangbang through the power of KISS. Yes, that KISS.

Purchasing Paperbacks From Hell via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.