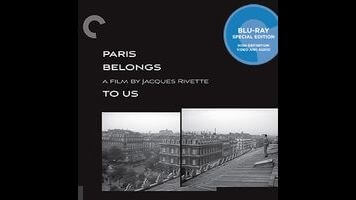

In the summer of 1958, a 30-year-old film critic and amateur filmmaker named Jacques Rivette started shooting a movie called Paris Belongs To Us, set a year earlier in a circle of young bohemians, actors, and expats. Rivette had come to Paris from Rouen to go to film school, but been rejected. Instead, he fell in with the tightly knit community that existed around the city’s film clubs. He wouldn’t finish Paris Belongs To Us until 1961, by which point it already felt like a time capsule. Many of the friends he had made in Paris—including François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Claude Chabrol—had become internationally famous directors, part of an era-defining movement called the Nouvelle Vague, or French New Wave. Rivette himself wouldn’t be able to make a career of film for almost a decade, eventually rising to cult status with his 1974 film Celine And Julie Go Boating. Paris Belongs To Us became one of the phantoms of the Nouvelle Vague; the new Blu-ray and DVD release from Criterion marks the first time it’s ever been available on home video in this country.

Rivette, who died of complications related to Alzheimer’s disease in January, was out-of-step from the start. The early movies of the Nouvelle Vague were typically one- or two-character affairs—stories about individuals or relationships, often urgent and fractured. Paris Belongs To Us, which runs a mammoth 141 minutes, has so many characters and it’s sometimes difficult to keep track; narratively, it feels more like a debut novel than a debut feature. There is a young student named Anne (Betty Schneider); a couple of Americans (Daniel Crohem and Françoise Prévost) in exile; intimations of conspiracy, both personal and global; a tape of guitar music recorded by a Spanish expat whose apparent suicide may have been a political assassination; cameos from Godard, Chabrol, and Jacques Demy; and some of the most depressing party scenes ever committed to film. More of a generational portrait than any of the other Nouvelle Vague debuts, Rivette’s movie presents mid-1950s Paris as a place where everyone seems to know and suspect everyone else.

It is awash in shadows: fears of global catastrophe, references to murky pasts, ominous and disquieting tensions, and, sometimes, even the literal shadow of the camera, belying the movie’s shoestring budget. It’s what Rivette and his film critic colleagues in the 1950s would have called a “film maudit,” a film doomed by its unique qualities. It’s both too studiously classical (in its sense of camera movement and shot composition) and too avant-garde (in its musique concrete score and unresolved plotting) to have ever become a fashion item. Its self-awareness is less edgy than defeatist. The opening epigraph (“Paris belongs to no one”) punctures the movie from the start. As in many subsequent Rivette films—including the monumental Out 1, which received its first-ever American release late last year—there’s a play-within-the-film seen exclusively in rehearsal: a production of Pericles, Prince Of Tyre, which echoes the movie’s paranoia while seeming to poke fun at its meager resources.

Like the aforementioned Out 1 and Celine And Julie Go Boating, Paris Belongs To Us structures itself as a journey into mystery, with Anne as a viewer surrogate. It has two deficits in that regard—namely, that the mystery isn’t all involving, and that Schneider isn’t much of a presence, her character rarely seeming like more than a naïve blank slate. Rivette started making movies before most of his peers (his best-known short, the half-hour Le Coup Du Berger, is included on the Criterion disc), but took his time developing his style, which would eventually make him the most actor-centric filmmaker to come out of a movement that made directors into icons and introduced “auteur” into the cultural conversation. But in its mixture of Cold War paranoia and bohemian portraiture—the cramped rented bedrooms, feature-less rehearsal spaces, and endlessly flowing cheap wine—Paris Belongs To Us remains unique: A movie that is at once “of its time,” and doesn’t seem to belong anywhere except in the place it creates within itself.