At this point, HBO’s real-life-scandal-based TV movies—its Emmy-bait character studies of influence and notoriety, its Profiles In Hubris—are something like an annual tradition. But the pay-cable titan’s long-in-the-works, Al Pacino-led drama about the fall of the popular Penn State football coach Joe “Joe Pa” Paterno is formulaic even by its own standards. Directed by Barry Levinson, who previously helmed HBO’s movies about the assisted-suicide proponent Jack Kevorkian (You Don’t Know Jack, also starring Pacino) and the financial fraudster Bernie Madoff (The Wizard Of Lies, starring Robert De Niro), it’s another artsy meditation on an American gargoyle in his sunset years, doddering around a private Xanadu of budgetary constraints and clumsy writing. Thankfully, we still have at a few years before this cycle catches up to Harvey Weinstein or the national Goodfellas “Layla” montage of the Trump administration.

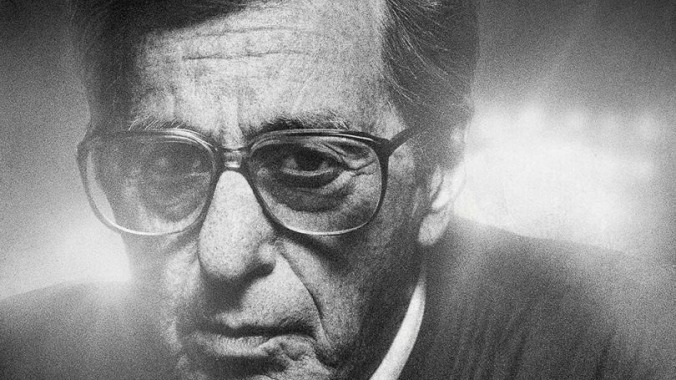

As the 84-year-old Paterno, who was ousted in 2011 after his former assistant coach Jerry Sandusky was arrested on dozens of counts of child molestation, Pacino dons yellow-tinted glasses and a prosthetic nose that looks like a Roma tomato. He is introduced moseying toward the camera in a heavenly white hospital corridor, some time before his death from cancer in early 2012. Loaded into an MRI machine, he flashes back to the glory of months ago: his record-setting win against the University Of Illinois’ Fighting Illini, set to bombastic music that makes it sound like the octogenarian coach is about to be awarded Hero Of Socialist Labor by the Soviet Union. The MRI scan provides Paterno with a bizarre framing device, as the movie periodically cuts back to the coach lying helplessly in the narrow tube of the machine (it’s what they call “symbolism”), watching as scenes are projected on its cylindrical wall, sometimes with unintentionally comical emphasis. (Cue a close-up of Paterno’s wildly swiveling eyes as the words “All these kids… all these kids… all these kids…” echo through his head.)

In other words, this isn’t what one would call an elegantly coordinated narrative. Making a secondary protagonist out of Sara Ganim (Riley Keough), who won a Pulitzer for her work on the charges against Sandusky and Penn State for The Patriot-News of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, might seem like a no-brainer straight out of Screenwriting 101. But Debora Cahn and John C. Richards’ amateurish script opts to just have random characters shout exposition at the journalist (“Joe Pa made an ethos in this whole place!”), as though she were having the scandal reported to her instead of reporting on it. Bewilderingly, the question of whether Paterno knew about accusations that Sandusky was molesting young boys (he did, since at least the late 1990s) and helped sweep said accusations under the rug (of course he did) are placed at the center of the film, when it’s clear that the more interesting question is “Why?” A drama about sexual abuse and institutional corruption might seem topical, but all Paterno offers its audience is a chance to re-experience the cable news cycle of yesteryear.

Writing aside, Pacino’s Paterno is an intriguingly slumpy, sluggish, distracted figure. Having also played the title role in HBO’s David Mamet-directed Phil Spector, the actor is as much of an old hand at these things as Levinson, and he avoids bluster, instead stretching the raspy and burpy notes in his voice, playing the disgraced coach as a man confused by his own downfall. In fact, there are enough quality performances in Paterno—most notably from Greg Grunberg as Paterno’s son, Scott, and from Kathy Baker, who has a smaller role as the coach’s wife, Sue—to make one wish there were a better film to support them. One can’t help but play shoulda-woulda-coulda with the fact that Paterno began life as a reunion project for Pacino and his Scarface and Carlito’s Way director, Brian De Palma—by most accounts a very different film that would have focused on the relationship between Paterno and Sandusky. At the time, John Carroll Lynch was cast as the latter; in Paterno, the character is basically a non-speaking role, played by a jobbing actor named Jim Johnson, whose IMDB page offers a Tobias Fünke-esque collection of headshots.

To say that Levinson lacks formal chops of someone like De Palma would be an understatement. Enlisting the Hungarian cinematographer Marcell Rév (White God), he directs in the style that has increasingly come to pass for “creativity” in our age of prestige TV—that is, randomly placed wide-angle lenses and gelatinously shallow depth-of-field that presumably symbolizes the myopia of the characters, but mostly looks like the work of a film student who just got their hands on a T1.3 aperture for the first time. These entry-level distancing effects (see also: the MRI machine) never succeed in hiding or overcoming Paterno’s flimsiness as drama, its tendency to pass off the obvious as revelation. Is there a dark side to every success story? Probably. But the only cogent insight about society at large to emerge from HBO’s ongoing project to turn every fall from grace that makes the news for more than a week into a TV movie is the fact that there remains no shortage of material.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.