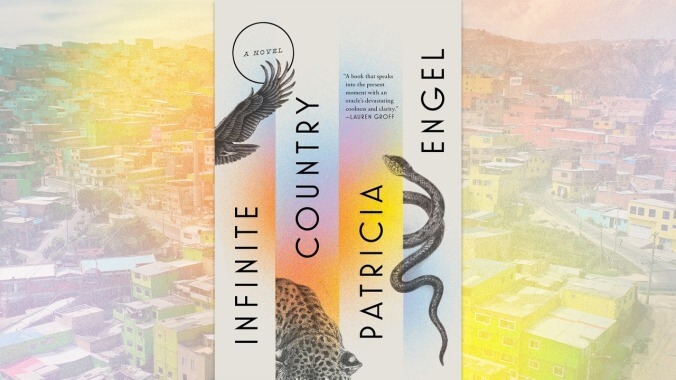

Patricia Engel explores an Infinite Country of immigration stories in her breathless new novel

In the compulsively readable Infinite Country, author Patricia Engel travels between all manner of borders, figurative and otherwise. The 2011 PEN/Hemingway finalist moves from the intimate—taking inspiration from the lives of family members—to the universal, in the shared history of migration. Many storytellers get tripped up on such a journey, as they end up crafting either what’s deemed too specific a story (and “not relatable enough”) or, in an attempt to represent what is actually a disparate group of people and cultures, they reduce individuals to totems. While Engel’s expediency with detail occasionally prevents parts of the story from taking root, it keeps the novel from stopping in its tracks.

As its title suggests, Infinite Country works to acknowledge the breadth of immigration experiences, though Engel homes in on a family split between the U.S. and Colombia. Only first names are used throughout; the Colombian American author finds more powerful ways than a shared apellido to unite this multigenerational family, even as decades pass, tragedies are endured, and oceans are crossed. Talia is our initial guide to Colombia, though at the moment of her introduction, she’s trying desperately to make her way out of the country. The teen has just escaped a girls’ reform school in a remote town, and is trying to make her way back to Bogotá, where her father, Mauro, and an airplane ticket to the United States await her.

The suspense of the opening chapter is characteristic of Talia’s story, but Engel elevates the plot beyond mere thriller. Even as the clock runs down and Talia finds herself closer than ever to being back at her mother Elena’s side in the U.S.—some 14 years since Talia, a U.S. citizen, was sent to be raised in Colombia by her grandmother Perla—she’s ambivalent about her destination. She’s not sure if she’s leaving or returning home, or if, in some physics-defying manner, she finds herself in both states. For Talia, the idea of home has been presented as “a house or an apartment, the place a person returned to at the end of a long day. The place where one’s family lived even if they left it a long time ago. The place one felt most comfortable.” And yet, “all these notions contradicted her first sense of it”; even if home does mean family, things are still pretty complicated for Talia, whose father and grandmother are in Bogotá, while her mother and her two siblings, Karina and Nando, have been living in New Jersey. In conveying just how commonplace this predicament is, Engel is devastatingly efficient: “[T]his particular family condition was so common it couldn’t possibly be considered trauma.” The author isn’t aiming to diminish Talia’s plight or have her family stand in for countless others—rather, Engel is underscoring the long-reaching effects of colonialism in Latin America.

Ever the fleet storyteller, Engel doesn’t task Talia with illustrating this additional element in the larger narrative. It’s through Mauro—who first traveled across Colombia, then past the equator and over the Atlantic—that Infinite Country taps into the country’s past, venturing almost to the primordial. Mauro’s had to seek opportunities in new towns and cities since he was a child, effectively abandoned by a mother for resembling the husband who’d let her down. He hasn’t had the luxury, the swelling pride, to call any one place home. Having survived paramilitary death squads and lived through the Colombian Conflict, he fears that his disillusionment with his homeland has poisoned his wife, keeping her in the U.S. for years after he was deported.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.