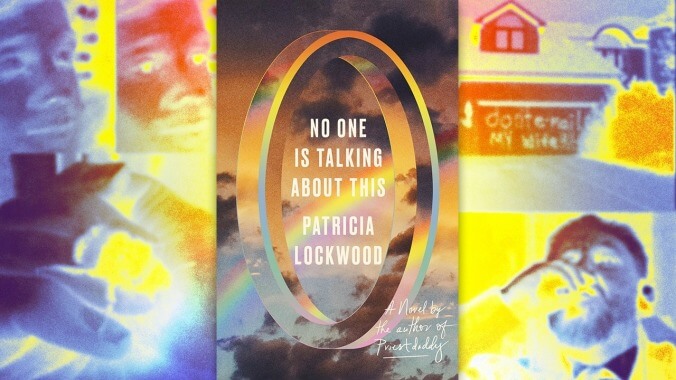

Cover image: Riverhead

Two years ago, almost to the day, The London Review Of Books published the text and video of Patricia Lockwood’s lecture “The Communal Mind.” Lockwood delivered the lecture a week prior at the British Museum, where—accompanied by a power point of tweets, emoji, GIFs, and viral photographs—she conveyed through vivid, figurative language and an animated performance what it feels like to be extremely online. Who better to hear from on this topic than the “poet laureate of Twitter,” the woman who once tweeted at The Paris Review, “So is Paris any good or not.” It was the rare perfect confluence of subject and writer, the kind that propels an already exceptional artist to the height of their powers.

Much of the text of that hour-long, nearly 7,000-word lecture can now be found offline as well—folded into Lockwood’s first novel. Like her essay, No One Is Talking About This begins as a slow immersion, a smattering of gentle impressions of life on the internet: “Close-ups of nail art, a pebble from outer space, a tarantula’s compound eyes, a storm like canned peaches on the surface of Jupiter…” Not unlike the author herself, the very online protagonist is something of a celebrity. The unnamed 36-year-old became internet-famous for posting “can a dog be twins,” and has since been invited to speak at forums across the world about “the new slipstream of information.”

The protagonist’s expert knowledge arises from her addiction, of not being able to pull herself away from her screens. “When she set the portal down, the Thread tugged her back toward it… This might be the one that connected everything, that would knit her to an indestructible coherence,” Lockwood writes. She isn’t losing herself to conspiracy thinking or radicalization, but to a nebulous hunt, not connected to any single ideology or goal, and one that will be familiar to anyone who loses hours to the internet but cannot quite say why.

The woman has another, “real” life—she has sex with her husband, she texts jokes to her siblings, she takes a bath—but for the novel’s first half, her waking hours revolve around “the portal” and a worry over her resulting porousness. The internet is no longer where you express your thoughts, she fears, but where your thoughts are dictated to you. There is the sense of giving oneself over to the masses. “Why were we all writing like this now?” she wonders. Because, she thinks, “it was the way the portal wrote.”

One could say this book writes the way the portal writes. Lockwood—who published two poetry collections before her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy—lays out her novel in brief, paragraph-length fragments. As with Jenny Offill’s Weather or Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, the novel’s form mirrors how information arrives to people through social media: piece by piece, in an unending stream, one fragment often unrelated to the next. The hilarious and the horrific and the mundane are all presented one after the other: “PantsBurnLegWound” is followed by a video of yet another Black man being killed by police, which is followed by “someone who made a heinous substitution in guacamole.”

A similar collapse of comedy and tragedy occurs when the plot emerges halfway through. The protagonist’s younger sister becomes pregnant with a baby that has Proteus syndrome, a rare disorder thought to be the same that afflicted Joseph Merrick, better known as the Elephant Man. The doctors believe that, if born, the child will not live for long, if at all; but the sister lives in Ohio, where laws are not kind to women who want to end their pregnancies. The book is thus cleaved, and this cleft brings to mind the take-no-prisoners opening of the William Gay short story “The Paperhanger,” where he describes a child’s disappearance as “so cataclysmic that it forever divided time into the then and the now, the before and the after.”

Up until this point, the third-person perspective has moved like a single eye, untethered and bodiless, roving within the eternal blue light of a computer screen. Now, suddenly, the protagonist is called back from her travels to care for her sister and the baby that, if she lives, “would live in her senses.” It’s not quite the mind-body divide, but Lockwood places the two side by side like photo negatives: the disembodiment of the internet and the supreme embodiment of a baby with a severe physical disability.

Lockwood’s humor, considerable throughout, becomes even more potent in the second half. The quaking, manic pulse of it beats within the family’s ordeal, leaving little air between the comedic and the poignant. One moment, the baby’s head is growing so large she cannot turn it; the next, they are all listening to Carlos Santana’s “Smooth.” As the doctors call dibs on the baby’s umbilical cord blood and the placenta, the protagonist thinks, “Messy bench who loves drama.” The internet’s voice is still inside them, but it is now also a balm.

So much of the book is concerned with how it feels to be extremely online and how it feels when “real life” takes one away from the internet, which makes Lockwood’s use of metaphor especially effective here. As in her poems and her memoir, Lockwood’s language remains colorful, absurd, ribald, transcendent. She may begin a sentence with a hushed lyricism, then pierce it with internet slang and coarse usage. In her visceral, often cartoonish prose, Lockwood does not take for granted that so much of what happens on the internet—the mimicry, the irony, the posturing—is merely the way things must go. Despite how often the book appears to be a “snapshot” of the internet during the Trump years, Lockwood isn’t taking a photograph; she’s bending reality back to its own strangeness.

No book so dedicated to the specifics of social media will ever feel entirely “current” to its reader. It’s no surprise that the memes and shared phrasing are already outdated: “shoot it in my veins,” “This Is Just To Say” as a tweet template, “Cat Person,” the maddening overuse of “normalize,” and of course the thing about eating ass. In some ways, the novel acts as a greatest and worst hits of the 2017 internet. (Judging by how much readers recognize, it’s also a quiz on just how online they were during this time.) To this point, I would be remiss not to include this line: “And if someone doesn’t, she thought, how will we preserve it for the future—how it felt, to be a man around the turn of the century posting increasing amounts of his balls online.” The endless scroll is slippery and swift. No One Is Talking About This plants a flag amid rushing waters.

The novel’s latter half is a memorialization of a different sort—that of a single life. The attention the protagonist once gave to the internet is now turned to a child. It can’t be overstated how daring Lockwood is in these passages. She risks the maudlin, the sentimental, the far-too-much. So many writers fail with far safer material. Lockwood bridges the high and the low, the profane and the holy, Garfield and a baby having a seizure. In the beginning, the protagonist worried about her mind, of no longer knowing “where she ended and the rest of the crowd began,” but not all porousness is bad. With this novel, Lockwood shows what can happen when you open the door wide and let everything in.

Author photo: Grep Hoax