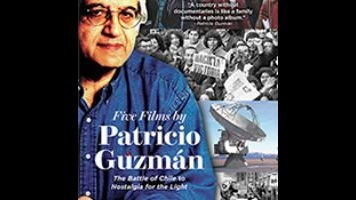

Patricio Guzmán tells his story of Chile in an essential new box set

This probably isn’t the ideal way to go through Patricio Guzmán’s documentaries, but Icarus’ new eight-disc DVD box set Five Films By Patricio Guzmán does make sense when watched in reverse order. Start with Nostalgia For The Light, the multi-award-winning 2011 essay-film, which has the director out in Chile’s Atacama Desert, interviewing astronomers and searching for the bones of the citizens that Augosto Pinochet’s government “disappeared” in the 1970s. This is the work of a nearly 70-year-old artist, trying to gain perspective on a lifetime of documenting the ramifications of what he sees as the pivotal moment in Chilean history: when General Pinochet’s army violently ousted the democratically elected Marxist president Salvador Allende. As Guzmán turns over old rocks and gazes up at the glow from distant stars, Nostalgia For The Light considers how the past shapes the present. It’s a haunted, quietly despairing film, pondering whether the passage of time obliterates meaning.

The rest of Five Films is about drawing closer to the moment of truth. The 2004 bio-doc Salvador Allende gathers personal reminiscences about the man whom Guzmán didn’t just support, but lionized, and there’s something anxious about the exercise. (Guzmán’s like a longtime fan, revisiting an old favorite’s early work to see if it still holds up.) Salvador Allende also plays like a palate-cleanser after 2001’s The Pinochet Case, which deals with the frustrations of the dictator’s victims, as they await a war-crimes trial that the international community seems reluctant to conduct. The two documentaries work as companion pieces. The Pinochet Case is the more urgent of the pair, and more historically important. It captures the debate about Pinochet as it was raging, and answers any concerns about the precedent of convicting a national leader by recording the testimony of Chileans who’d seen their families torn apart. Then, to counter anyone who’d suggest that the 1973 military coup in an economically depressed Chile was inevitable and even necessary, Salvador Allende argues that the nation actually had the right man in charge, even if the U.S. government and the upper-classes were determined to sabotage him.