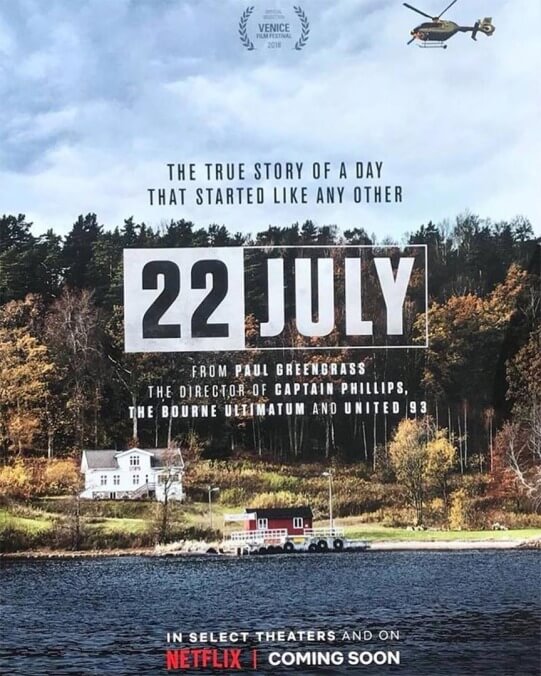

What a perverse niche Paul Greengrass has carved out for himself. When not training his erratically jerking camera on a motorcycling Matt Damon (he’s made three of those Bourne sequels, beloved by action junkies immune to motion sickness), the British filmmaker has found his calling meticulously dramatizing acts of harrowing, world-shaking violence: the Bloody Sunday massacre of ’72, the terrorist attacks of September 11, the hijacking of a cargo ship by Somali pirates in 2009. No question these films are intense and immersive—Greengrass has become something of an expert at making viewers feel like they’ve been transported to the day(s) in question, experiencing headline horrors in a minute-by-minute present tense. But there’s also something just a little… ghoulish about making white-knuckle thrillers out of real-life tragedies, however thoroughly the sensationalism is coated in this-is-how-it-really-happened verisimilitude. And with 22 July, Greengrass pushes up against the boundaries of respectful representation, traipsing queasily close to outright exploitation with his reenactment of the 2011 Norway terrorist attacks, which claimed the lives of 77 people, many of them children.

For a while, the film unfolds in the same cross-cutting, omniscient docudrama mode as United 93, tracing the accepted timeline of the fateful day. We see someone calmly, methodically gathering weapons and explosives. We see the first of his lone-wolf attacks, the detonation of a car bomb in Oslo, sending local authorities and government officials scrambling to respond. And we meet dozens of teenagers gathered at an island summer camp for a leadership conference.

It’s pretty icky, watching kids—largely unidentified by name—obliviously go about their young lives, unaware of their own impending slaughter. And that discomfort bottoms out into a deep nausea once the culprit, Anders Behring Breivik, arrives by ferry, two hours after the explosion in Oslo, disguised as a police officer and carrying an assault rifle. These scenes should make us sick, of course. How else should an audience feel when confronted with images of teenagers cowering in fear, pleading for their lives, being gunned down for the supposed sins of their parents and country? But there’s more than clear-eyed moral repulsion in Greengrass’ staging of the atrocity, which left 68 dead and many more forever traumatized. He also gooses the suspense here and there, playing with our concern for the “characters” he’s granted actual speaking lines and identifiable personalities—a gross choice, frankly, especially during an offensively titillating moment that hinges on whether the killer can successfully reload a dropped clip in time to pick off a kid who’s knelt to attend to his critically injured older brother.

Remarkably, this is actually 2018’s second cinematic depiction of the attack. Norway’s own U – July 22, which premiered at the Berlin Film Festival this February, devoted itself entirely to what happened on the island, unfolding in real time and via a single take to capture the subjective experience of the victims. Greengrass, for all his peculiar interest in thrusting audiences into the waking nightmare of recent events, takes a broader tact. After the you-are-there immediacy of the extended opening act, 22 July shifts gears into a trifurcated and surprisingly conventional depiction of the aftermath. The film follows the fates of three characters: the perpetrator (Anders Danielsen Lie), a right-wing extremist seeking a courtroom platform for his abhorrent white nationalism; liberal attorney Geir Lippestad (Jon Øigarden), specifically requested by the shooter, who agrees to represent him because of his belief that everyone deserves a fair defense; and one of the survivors, 18-year-old Viljar (Jonas Strand Gravli), whose rehabilitation is complicated by his imperative to testify at the trial.

22 July clearly sees these figures as avatars for the conflicting forces of Norwegian identity: a rising tide of nationalist hate pitted against democratic nobility, plus an overwhelming public urge to move on from the tragedy. In practice, though, the competing threads play like two mediocre movies—a banal legal drama, a banal recovery drama—twisted inelegantly into one. In a bizarre concession to the subtitle-averse (possibly mandated by Netflix), Greengrass asks his all-Norwegian cast to speak solely in English—a decision that compromises the authenticity his movies cling to like a badge of honor, to say nothing of how it disadvantages the performers. Lie, who lent his haunted features to two very good movies by Joachim Trier, does his best to make this murderous zealot a complicated character—a weak, delusional man convinced he’s reshaping the world around his principles. But the film often treats him more like Hannibal Lecter or a comic book supervillain, delivering diabolical monologues about his righteousness before his inevitable vanquishing in the courtroom. For all the care he takes not to let the bad guy “win,” there’s an uncomfortable sense that Greengrass has given the real-life terrorist something close to what he wanted: a chance to commandingly voice his toxic ideology, albeit here through fictionalized depiction.

We get why Breivik committed these crimes. Neither the man nor the movie leaves that a mystery. The real question mark concerns 22 July itself and how this unproductively unpleasant movie hopes to justify the experience of enduring it. Is topicality enough? In rewinding back a few years to a violent expression of racist paranoia, Greengrass finds a reflection of today’s conflicts in yesterday’s news—and maybe, issues a warning that something like this could easily happen again, so internationally bolstered are the hatemongers of Breivik’s ilk. But 22 July’s climactic extolling of love over hate—morally unimpeachable though it may be—feels like thin rationale for dragging us through a horror-movie simulation of a truly dark day. The attack sequence lasts only a few minutes, but the bad taste it leaves in the mouth can’t be washed out so quickly.