Paul Verhoeven is back with a vengeance with the corrosive Elle

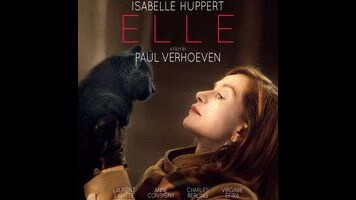

Elle opens with a wealthy and beautiful middle-aged Parisian being raped on the parquet floor of her first-floor den by an intruder in a ski mask. The only witness to the attack is a black cat, which sits watching silently. This is the first image, the cat’s stare, a touch that’s grotesque and mysterious, like everything that follows in this deviously plotted and subversive black comedy. The woman, Michèle Leblanc (Isabelle Huppert), sweeps the broken glass into a dustpan and throws away her clothes. She has dinner with her son. She goes to sleep holding a hammer. The following morning, she arrives at her office like nothing happened, slinging her designer handbag.

It’s become a cliché of art films: the traumatic act of violence whose blank non-acknowledgement is a putative structuring absence that recasts banalities in a light of alienation or unsettlement and so on. But that’s too simplistic for Paul Verhoeven, who’s made a career out of having his cake and eating it too. He is both a provocateur and a gonzo craftsman; from Dutch successes (Soldier Of Orange, The Fourth Man) to Hollywood sci-fi blockbusters (RoboCop, Total Recall, Starship Troopers), the director has found a way to merge dark satirical wit with a taste for excesses of sex and violence. Elle is a challenging film, but challenging precisely because it’s entertaining, because it’s laugh-out-loud funny, because it indulges its kinks.

One conundrum is that Elle is singularly a Verhoeven film, but doesn’t quite look like one. Adapted from “Oh…”, a recent novel by Philippe Djian (author of the source novel for the semi-notorious Betty Blue), it adopts a decorous coolness reminiscent of the bourgeois suspense films of Claude Chabrol and, at times, the surreal subversions of upper-class mores and relationships of Luis Buñuel. Set around Christmas and shot on location around Paris with an exclusively handheld camera, it shrouds itself in ordinariness (there are too many scenes involving parking troubles and restaurants to count) in much the same way as Verhoeven’s Hollywood films would wrap their sharpest points in special effects and action thrills. The result is rivetingly unpredictable, lurid, and black as pitch.

At every opportunity, it veers a sharp left, into deadpan farce and satire, avoiding most conventions of progress and suspense. Michèle is the CEO of a video game company, where she exhorts her all-male team of designers and programmers, “When the player guts an orc, he needs to feel the blood on his hands.” Her ex-husband, Richard (Charles Berling), is a pathetically obscure novelist who is trying to pitch her an idea for a game about a post-apocalyptic revolt of cyborg dog slaves. Her mother (Judith Magre) lives with a gigolo. Her father, about to be denied parole for the umpteenth time, is France’s most notorious serial killer. And, of course, there are the violent fantasies that Michèle initially entertains about getting back at her rapist, whose identity she discovers a little more than halfway through the movie.

Even there, Elle denies the expected cat-and-mouse payoff: The bravura final act is a study of stomach-churning psychosexual dynamics and the façades that normalize exploitive behavior. One of the most dazzling and provocative gambits of the narrative is the fact that Michèle, the anti-victim in black nail polish, embodies just about every negative stereotype ever used to rationalize misogyny. She is a bitchy boss, an openly disapproving mother to her dimwitted son (Jonas Bloquet), and a jealous ex to Richard, who is trying to date a much younger yoga instructor. She is screwing the husband of her best friend, Anna (Anne Consigny), and trying to seduce her square-ish married neighbor, Patrick (Laurent Lafitte).

Huppert’s performance is marvelous and intuitive, one of the best of her career. It’s indelible because, like the film itself, it refuses to recognize any contradictions in her character. The closest Elle provides to a thesis statement is something Michèle says to Anna late in the film: “Shame isn’t a strong enough emotion to stop us doing anything at all.” Verhoeven’s films have often held to the principle that nothing is more subversive than pleasure. In Michèle, he and Huppert have created a character who strikes back at those who think she’s overbearing or sociopathic (i.e., almost everyone except Anna) by relishing jokes at their expense and who entraps a rapist in her own rape fantasies. One might call her a feminist antihero, but Elle denies that there’s anything anti- about her.

David Birke’s fluid screenplay, which was written in English and subsequently translated into French, encompasses dozens of incidents and indiscretions, as well as the deaths of multiple characters, several affairs and relationships, and Michèle’s secret campaign to find the source of a video that was sent around her company, a crude animatic that shows her being raped by a monster. This is one of the most impressive things about Elle as a feat of filmmaking: that so few of these converge, but instead develop and complicate a central theme by way of digression.

We learn, for instance, that Michèle has been a subject of morbid public fascination since childhood, a symbol of corrupted innocence, rumored to be an accomplice in her father’s killing spree. There’s a ravishing sequence, nearly gothic in its romanticism, in which Michèle has Patrick help her close the storm shutters on her house during a freak windstorm. There’s the farce of her personal life: her open hostility toward her son’s pregnant girlfriend, her attempts to sabotage Richard, her voyeuristic tendencies, her self-admitted attraction to dumber men. Michèle and Elle are one (the title translates as She); both are equally engrossing, caustic, and seemingly contradictory.

It’s the trap that Elle lays out for the viewer. It gives them every opportunity to think of Michèle—and, by extension, the film—as hypocritical. But Verhoeven, through his deceptively casual direction, affirms that one can be aroused and even empowered by violence and surveillance as fantasies and still be traumatized by them as real events. (The parallels to Michèle’s video game company are never made blatant, but they’re there.) What does it say about the world we live in that a movie that takes for granted that rape and sexual harassment are about power, not desire, qualifies as one of the most corrosive and fruitfully challenging works of art in recent memory?