PBS’ Hemingway is an immersive portrait of the author’s brilliance and cruelty

When modern readers lambast the American literary canon, they’re probably complaining at least partially about Ernest Hemingway. The Hemingway clichés are easy to rattle off: a thrill seeker who fetishized bullfighting and big-game hunting to prove his manliness; a womanizer who was always on the lookout for his next wife; a wartime bystander who co-opted the violence and trauma of the Great War to make a name for himself as a writer. To use the language of Hemingway admirer J.D. Salinger, the man’s uber-masculinity sometimes had a phony stink.

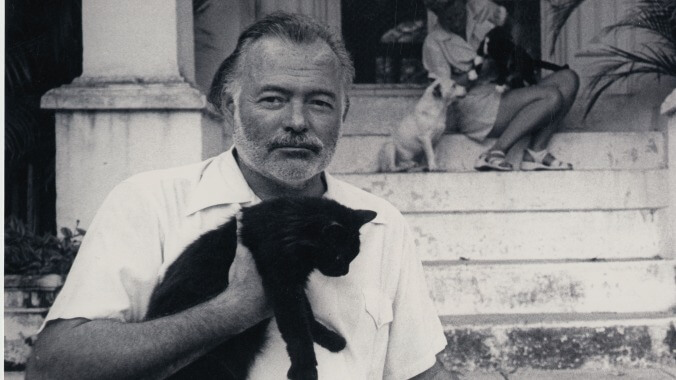

To its credit, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s six-hour docuseries Hemingway doesn’t dispute much of this. The directors use the author’s own statements, letters, photographs, and other writings to verify some of our worst assumptions. As cultural conversations about whether we can separate the exemplary work of an artist from their problematic personal life resurface over and over again, Hemingway wades into that same muddy water and throws down its anchor. The result is a docuseries that acknowledges what it doesn’t definitively know about Hemingway—did his sexual experimentation suggest questions related to his gender identity; did all the concussions he suffered contribute to mental illness?—while doing its best to paint a full portrait of the artist and the man. Hemingway seems to come down a certain way on whether his moral failings overshadow the beauty and exemplary quality of short stories like “The Snows Of Kilimanjaro” and novels such as The Sun Also Rises or A Farewell To Arms, but Burns and Novick also leave space for viewers to make their own decisions.

Hemingway charts the entirety of the author’s life, dividing it into three chunks that are engagingly written by Geoffrey C. Ward and evocatively narrated by Peter Coyote, both longtime collaborators of Burns and Novick. First is “A Writer,” which depicts Hemingway as a “troubled and conflicted man, who belonged to a troubled and conflicted family.” His father was a family doctor who saw many patients die during childbirth; his mother was a former opera singer who resented her children. To amuse herself, she often dressed Ernest in girls’ clothes and pretended that he and an older sister were gender-swapped twins. Desperate to escape from the stifling, prosperous Chicago suburb in which he grew up, and increasingly hostile toward his mother, whom he blamed for his father’s late-life paranoia and instability, Hemingway began writing for The Kansas City Star at 17. (The newspaper’s style guide encouraging “vigorous English” is a particularly enlightening detail.) After turning 18, Hemingway’s time as an ambulance driver in Italy in World War I would profoundly change his life, and Burns and Novick masterfully use archival footage, news reels, and Hemingway’s own photographs and letters (the directors were given access to his collection of materials at Boston’s John F. Kennedy Presidential Library) to chart the horrendous physical injuries he sustained on the battlefield, and the heartbreak that came afterward.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)