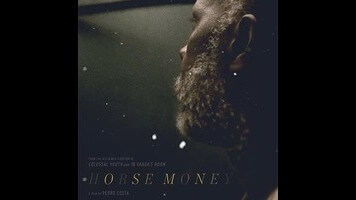

Pedro Costa returns to the dreamworld with Horse Money

Does Pedro Costa—the Portuguese master of the sparse, dreamlike art film—aestheticize poverty? Coming almost a decade after Costa’s last fiction feature, Colossal Youth, Horse Money finds the director returning to his King Lear figure, a Cape Verdean immigrant named Ventura. Fontainhas, the shantytown whose demolition inspired Colossal Youth, is now long gone; what remain are ruins and memories, which, as far as Costa is concerned, are ruins of the mind. Costa’s M.O. is real people, real places, and real light, bent by mirrors to create a glow akin to minimalist noir crossed with Old Masters painting—cryptic visions of a purgatory unique to the migrant poor, cycling between memories of homes left long ago and slums that exist in a loop of obsolescence and abandonment.

When Colossal Youth hit the festival circuit back in 2006, part of what made it feel both monumental and otherworldly was the way it appeared to represent a direct encounter between past and future. Its sense of light, figure, and composition recalled the art of a much earlier time, but through the medium of digital video. The novelty never had time to wear off. Costa’s choice of format—consumer-grade MiniDV tape, framed in boxy 4×3—turned out to be something of a dead end, the result being that Colossal Youth now seems like a movie out of time. So does Horse Money, which keeps to the earlier film’s look, albeit at a higher resolution, and adds shades of German Expressionism of the Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari variety.

Sleepwalking through a role is just about the worst insult you could level at an actor, professional or otherwise, but that’s more or less what Ventura—again playing a poetic representation of himself—does here. Ventura, who is somewhere around 60, cuts a striking figure. He has deep, glimmering eyes framed by a bare brow line. Dressed in striped pajamas, he wanders the halls of an old-time insane asylum, sometimes seen as a modern-day hospital; his hand tremors, the result of a head injury, bring to mind a body convulsing in nightmare. I Walked With A Zombie, one of Costa’s biggest influences, could be an alternate title for this film.

Spatial and temporal confusion—the stuff of when and where—are the order of the day; a viewer is never sure who or what might be a figment or a phantom. Costa’s films could never be mistaken for conventional realism. They hew too closely to the transformative logic of dreams. But whereas earlier, longer works like In Vanda’s Room and Colossal Youth had a definite documentary edge, Horse Money dispenses with any claims to observational filmmaking. These people may be playing themselves and they may be talking about their own experiences, but in an underworld of Costa’s imagining. Though his subject matter is stark and serious, no one could accuse him of lacking a sense of humor. There are glimmers of demented comedy in the riddle-like dialogue and in the hunched movement of the non-professional cast. And there is, as always, a powerful sense of poetry, both to the dialogue—much of it seemingly spoken in blank verse—and to the editing, which eschews continuity as though it were a constraining type of rhyme.

One used to get the sense that if Fontainhas—the setting of all of Costa’s fiction films since Ossos, populated by the addicted and under-employed—hadn’t existed, then the filmmaker would have invented it himself. Here, he opens with a montage of photographs from How The Other Half Lives, Jacob Riis’ pioneering study of urban poverty in 19th-century New York, suggesting that the subject at hand is less what remains of the demolished Lisbon slum—which is nothing but memories, unpaid wages, and death certificates—than the larger experience of those who go north and west in search of work. “We always lived and died this way,” remarks a character. “This is our sickness.” The “we” is left intentionally vague.