During last year’s presidential primaries, The New Republic, the century-old liberal magazine of arts and politics, posted (and quickly deleted) a tweet to the future commander in chief: “fuck me daddy.” The tweet’s author, poet and now memoirist Patricia Lockwood, had taken over the publication’s Twitter account when it published her piece “Lost In Trumplandia,” which chronicled the disorienting, visceral experience of attending a Donald Trump rally. The prank was squarely on-brand for the writer, whom The New York Times once deemed the “smutty-metaphor queen of Lawrence, Kansas.”

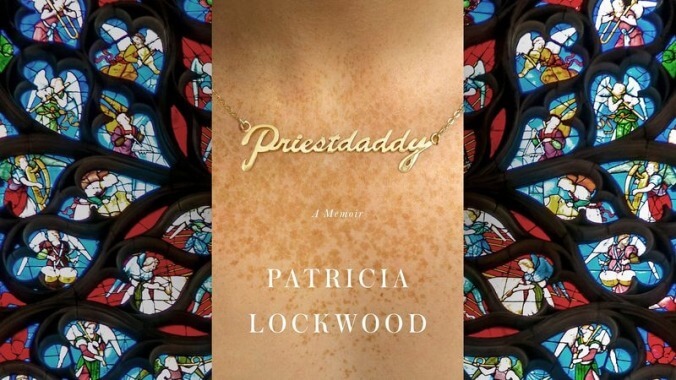

Lockwood’s newest work, Priestdaddy, a hilarious and affecting account of growing up with a married Catholic priest for a father, follows two collections of poetry: 2012’s Balloon Pop Outlaw Black and 2014’s Motherland Fatherland Homelandsexuals, which includes “Rape Joke,” a poem that went viral after a controversial stand-up set by comedian Daniel Tosh.

The memoir is centered around a nine-month period when Lockwood and her husband, Jason Kendall, lived with her parents after Kendall underwent an expensive eye surgery for rare advanced cataracts. Lockwood’s re-immersion into her wacky parents’ lives serves as a jumping-off point for examining the formation of her artistic aesthetic—and as an opportunity to flex her comedic muscles. There’s a great deal of pleasure in her line-by-line writing; the author can describe even a seminarian’s ordination ceremony in a colorful, unexpected way, her prose dyed with bizarre sexuality, religious eroticism, and slapstick timing. Lockwood churns out oddball imagery at a breakneck pace, and she, luckily, has a lot of material to work with.

Priestdaddy’s titular Father/father is the kind of oversized personality one would strain to believe in fiction. The jolly tyrant plays face-melting prog rock—“He practices mostly behind half-closed doors, so it’s possible he’s having sex with the guitar? It’s possible that somewhere out there I have a half brother who is a sweet lick from the waist down?”—and is, within his home, always half-naked: “‘There’s no in-between with him, is there. He’s either buck nude or he’s in a little outfit,’” says Lockwood’s husband, who’s no slouch in contributing his own one-liners. Like a supporting sitcom character, the author’s mother, an extreme worrier taken in by conspiracy theories and urban legends, has a knack for popping into a room to say the one thing that perfectly contradicts or supports the extant conversation.

While Lockwood meanders at times within the episodic structure—a drunken church dinner, a trip to the “nation’s wang” of Florida—she anchors the book with insights into how she, an atheist surrealist poet, could have possibly come from these two distinctly nutty people. Her obsessive writing, her preternatural ability to form nearly any idea into language, she admits, is not so different from her father’s religious devotion. Lockwood and her mother’s shared love of ribald wordplay, for example, is exemplified in the chapter “The Cum Queens Of Hyatt Place,” wherein the two discover stained sheets in their room during a trip and devolve into an extended pun exchange. These stories can appear solely comedic at first blush, but it’s not hard to see what Lockwood’s getting at: “As kooky as these people are,” she seems to say, “I’m most certainly their daughter.”

Even when not mashing up sex and religion, Lockwood’s metaphors are tactile and evocative, her poignant turns of phrase shining that much brighter for being placed within all the dick jokes and knocks to Catholic fanfare. She’s particularly affecting when she writes about her attempted suicide at 16 and nearly breaks into song when describing her creative impulse: “My mother and I are after perfection. We are seeking a particular click in the head. We share the feeling that if we hang a picture or set a sentence down just right, we will instantly and painlessly ascend to the next level. We will be recognized, and the time we spent will be multiplied into forever and given back to us.”

The drawback to Lockwood’s boundless, loquacious energy is that the book goes on for far too long, with seemingly every potentially entertaining anecdote included. With the book spanning out like a long-running sitcom, its latter third feels like it won’t provide any new revelations. Which is to say, not all of Priestdaddy’s stories are necessary, though Lockwood’s bad mouth certainly is.

Purchase Priestdaddy here, which helps support The A.V Club

.