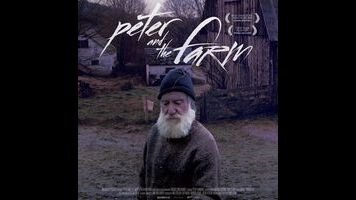

Whatever your conception of a farmer may be, Peter Dunning, the 68-year-old subject of Peter And The Farm, may deviate from it significantly. Dunning certainly looks the part, sporting a bushy gray beard and wearing comfortable sweater-and-jeans combos as he trudges around his 187 acres in Vermont, tending to his sheep and cattle. As soon as he starts talking to the camera, however, it becomes clear why director Tony Stone (Severed Ways: The Norse Discovery Of America) decided to fashion a documentary character study around this unusual man. Indeed, the longer the movie goes on, the more disturbing it becomes, to the point where viewers may start to fear that they’re witnessing the buildup to something truly awful. Thankfully, Dunning doesn’t follow through on his darkest impulses, but there’s enough rural angst on view here to justify Stone’s use of aggressive post-rock needle drops on the soundtrack. This is one tortured soul, and a rare case in which a farmer’s struggles seem to be entirely of his own making.

It takes a while to realize that Peter And The Farm has no particular “angle,” apart from Dunning himself. Dunning directly addresses the camera right from the start, but Stone doesn’t establish any sort of narrative hook, or even provide a clear reason for why he’d be making a movie about this guy in the first place. We’re simply thrown into Dunning’s daily routine, which involves a lot of alternately grim and tedious tasks (warning to the sensitive: animals are killed on camera) in which he seems to take little pleasure, even as he claims to care more about the farm than he does about himself. Gradually, depressing aspects of Dunning’s life emerge from his alternately acerbic and angry running commentary: His left hand was horribly mangled in a logging accident when he was 26, effectively putting an end to his dream of being a sculptor; he’s struggled with alcoholism for many years (and somebody, possibly Stone himself, keeps urging him from off camera to check himself into rehab); his wife left him long ago, and his children, he says, wouldn’t even bother to pick up the phone if he called them. It’s startling, but not surprising, when he starts casually talking about suicide, wryly noting that an apprentice keeps hiding his rifle.

Dunning is still alive when the movie ends, but anyone anticipating a redemption arc will be disappointed. There’s no callously indifferent bank official to be outwitted, nor any crop-ruining weather pattern to overcome. Peter And The Farm isn’t a lament for the difficult life of a family farmer—it’s a portrait of the inner turmoil experienced by this family farmer (minus the family). And it’s decidedly not the sort of life-affirming movie that pretends people suddenly turn a shitty situation around when they’re pushing 70. Indeed, the overall vibe is so despairing that Stone’s decision to soldier on can feel pointlessly sadistic at times, though Dunning is so cogent and garrulous that it never seems as if he’s being exploited. He’s an unforgettable figure, King Lear crossed with the Fool (at one point he starts singing West Side Story’s “Jet Song” for what’s initially no apparent reason), and that’s probably enough to justify the film’s existence. But watching him reflect on the sorry wreck that his life has become is no less tough than watching him struggle to unjam his rifle after shooting a lamb in the head the first time he fails to kill it. The desire to look away is strong.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.