Peter Weller on feminism, sequels, and more

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

The actor: Peter Weller began his acting career in New York theater, building a formidable list of stage credits before actively forging his path in front of the camera and appearing in such memorable films as The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension, RoboCop, and Naked Lunch. Although he’s worked a great deal on the small screen as of late, both as an actor and a director (after having directed seven episodes of Sons Of Anarchy, he’ll be stepping in front of the camera this season for a recurring role on the series), Weller recently returned to the realm of the big-budget motion pictures, appearing in Star Trek Into Darkness, now on home video.

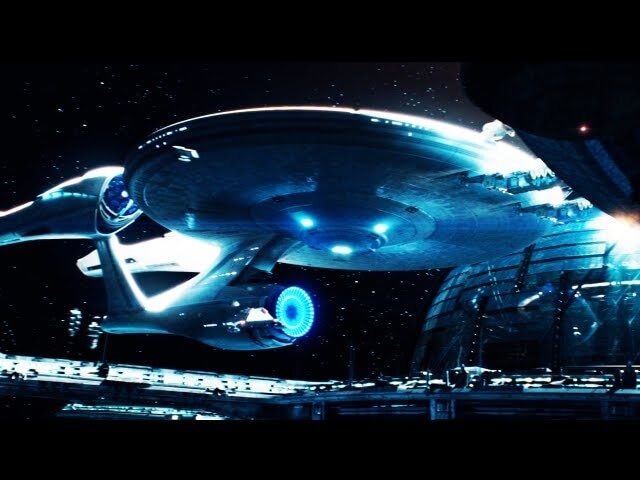

Star Trek Into Darkness (2013)—“Fleet Admiral Alexander Marcus”

Peter Weller: Well, first of all, I love the two names, because in my Ph.D studies in Italian Renaissance art history—my minor is classical art— Alexander is a seminal general, diplomat, ambassador of the Western world, and Marcus, I guess, comes from Mark Antony. Those are two classical statuaries of antique and modern history. So I loved the names, and the guy… he’s like Curtis LeMay gone wrong. A more interesting version of Curtis LeMay, I might say, but a guy who’s speaking the truth about a war that’s coming, that the people involved—the Klingons—are not going to negotiate, and certain extreme measures are going to have to be executed.

By the way, everything Marcus says in the film is true, which people forget. People go, “Bad guy! Bad guy!” But why is he a bad guy? Everything he says is true: The Klingons are coming, they do need Khan, and that’s that. It’s just that he’s going to sacrifice the entire Enterprise to get the job done, because the Enterprise started to believe Khan. But if the Enterprise had not believed Khan and had done what Marcus said, then there’d be no movie, and everything would be cool. [Laughs.] But the great writing in this is that the Enterprise wakes the dude up and listens to his game, and then everything goes to crap. But that’s the Enterprise’s hubris. That’s them. They screwed up, not Marcus. Anyway, sorry to go off there. I just hate that.

The A.V. Club: You’d been part of the Star Trek universe prior to this film, having guest-starred on a couple of episodes of Enterprise, but what’s your familiarity with Star Trek as a franchise? Are you a fan?

PW: I’m not a science-fiction fan. Well, you know, I guess I’m a fan of Philip K. Dick. I did a film called Screamers, based on “Second Variety,” his little novella, and I loved doing that thing. I admire certain pieces of science fiction, but I don’t read science fiction, I’m not a big Trekkie, and… I’m just not a big science-fiction guy. But creating alternative universes and alternative moralities is what I admire it for. I like to read about it. And I watched some episodes of Star Trek that they did in the ’60s, and there’s a couple of them that I really liked, but I didn’t watch it every week. I’m a big fan of Leonard Nimoy’s, though, because I did my third job with Leonard.

(Although Weller didn’t clarify what his “third job with Leonard” was, an email to his manager got us the answer: It was the 1973 play Full Circle, directed by Otto Preminger and starring Nimoy and Bibi Andersson, which started at the Kennedy Center before earning a brief run on Broadway. — Ed.)

The Man Without A Country (1973)—“Lt. Fellows”

PW: That’s the first thing I ever did. Was that his name? Fellows? [Laughs.] Yeah, with Cliff Robertson, Robert Ryan, Peter Strauss, and all those guys. Wow…

AVC: How did you find your way in front of the camera? Did you start in theater?

PW: I started in theater. I was in New York. I went to the American Academy Of Dramatic Arts, and I got an agent and a manager out of that. I still have the manager, but the agent’s retired. [Laughs.] Yeah, I was doing Sticks And Bones, the Tony Award-winning play. I was the understudy, and then I became the lead. Joe Papp gave me my first job at the New York Shakespeare Festival. And then I went in and played Lt. Fellows for [director] Delbert Mann.

AVC: Had you always intended to make the move from theater to on-camera acting, or was it just the way it panned out?

PW: Yeah, I wanted to make the move, but I wanted to do it on my own terms. I didn’t want to come out to L.A. and look for jobs. I wanted to be in New York. I loved the theater, I loved the people in the theater, I loved the history of the theater, and all the actors I admired came from the theater. And I followed their footsteps. I studied with Uta Hagen. I became a member of the Actors Studio under Elia Kazan. Both those people are heroes to me. Kazan directed Uta Hagen, as a matter of fact. She replaced Jessica Tandy in the original production of A Streetcar Named Desire. In fact, I’ve got a one-off poster right here—with both Marlon Brando and Uta Hagen in Streetcar. My best friend, who’s an antiquary book dealer, gave it to me. But, yeah, all of that New York history, that brilliant history of the theater, was the thing that attracted me to acting. And film, once one does film, you can’t… well, I don’t know, but I just fell in love with it. I fell in love with making movies.

Shoot The Moon (1982)—“Frank Henderson”

PW: Wow. I just showed that movie to my wife. I hadn’t seen it since it came out. What a brilliant movie, and how proud I am to be a part of that movie. You have to remember, that movie was made during… Now, see, I’m bringing up social and intellectual history here, but that movie was made during what was called the second wave of feminism. I’m ashamed to say that I’ve run into students now who have no idea that there was a social revolution in this country [in the ’60s], or in the world, and that people actually died. Whether you liked it or not, whether you understand it or not, you have to be aware of it. Like Cicero said, “He who is not aware of the history of the state is doomed to mental infancy forever.” And, you know, the history of America… I’m sad to say that they don’t teach the social revolution of the ’60s or Vietnam or anything. They stop with Kennedy. I guess there’s no point of… I guess there’s just too many points of view about that.

But after Germaine Greer, Betty Friedan, and Gloria Steinem—social revolution becomes a methodology in teaching everything. It doesn’t matter if it’s classics, humanism, the humanities, history, art, music, and musicology… whatever. You have to study the methodologies of the ’70s, and one of them is feminism. The second wave of feminism is when feminism, or the point of view of what female gender had in everything, became a huge part of filmmaking. Before that, you’ve got a couple of flicks, like I’ll Cry Tomorrow, about a woman going to the electric chair, and The Women, which was a brilliant play by Clare Bloom Luce. But in the ’70s and early ’80s, man, you’ve got three or four major, major films about women and their particular point of view… and one of them was written by the great Bo Goldman, and it’s Shoot The Moon.

When that movie came out, honest to God, I was sitting with an executive who was a friend of Frank Capra, and he said, “I got a compliment for you from Frank Capra.” I said, “Come on!” He said, “No, I just got off the plane with him, he’s an old friend, and he said you were fantastic in that film. But as fantastic as you were, the film is important.” I said, “What is Frank Capra saying about the importance?” I didn’t get it at all. Now I get it. Frank Capra was a guy who’s steeped in social comedies. That’s what he made most of his life. And he looked at Shoot The Moon, and he said, “Wow, this has really got something poignant to say about the survival of women in the United States, in particular women who’ve been buried in domestic situations and obviously have no out.” You have to remember, in those days, if a woman had an affair with someone she worked with, she could be fired. There was no maternity leave. Can you imagine that? Were we living under a fucking rock then, or what? I don’t understand it, man. But Shoot The Moon… I’m so proud of that movie. Sorry to wax on like that. But it’s a fantastic film, a real winner, and, by God, Diane Keaton’s performance is one of the great performances by anybody. That performance… you can’t recreate that, man.

Naked Lunch (1991)—“Bill Lee”

PW: Another winner. [Laughs.] That’s considered by Time-Life as one of the seminal pieces of literature in English in the last… well, in this century, anyway. It was a huge, very influential book for me in the ’60s. A phantasmagoria of social history done through the eyes of a guy who’s been a junkie for 18 years and has seen the ass end of the world and put it into poetry. To do that movie with David Cronenberg… I mean, it’s a very beautifully executed film by [cinematographer] Peter Suschitzky and Cronenberg, and with the great Judy Davis, my friend. I did two movies with her, and she may be the most brilliant actress… well, one of the most brilliant actresses. I’ve had the pleasure of working with her and Diane Keaton and Dianne Wiest, and those three actresses are unbeatable. Unbeatable!

AVC: What was your interaction with William S. Burroughs?

PW: A lot. I met Burroughs six months before we began the movie and remained in constant touch with him until his death. He informed me about several things, humorously so. This is another thing about social history. About gay rights, he said, “I’m not gay and I’ve never been part of a movement. I’ve never been gay a day in my life. I’m queer.” [Laughs.] It’s funny, by the way, because that whole methodology of looking at homosexual relationships and the advent of gendering in society is called queer theory, not gay theory. And queer theory is a legitimate methodology of looking at a world from the marginalized people who’ve been gendered gay or queer. So there’s another piece of social history that I got to be part of. Wow. An amazing movie, and an amazing book.

[pagebreak]

The Adventures Of Buckaroo Banzai Across The 8th Dimension (1984)—”Buckaroo Banzai”

PW: I had no idea what that movie was about, I still don’t, but I had a ball making it. They presented it at Lincoln Center a few years ago. [John] Lithgow and I went, and we admitted there that we had no idea what we were doing. It’s a miracle, that movie, just a miracle.

AVC: How serious did talks ever get for doing the promised sequel, Buckaroo Banzai Against The World Crime League?

PW: The promised sequel… If I had four or five dollars for every person who came up to me and asked me about a sequel, you and I could go to Las Vegas for a week. [Laughs.]

AVC: What if someone threw that money into a Kickstarter campaign to finally make one? Do you think it could still happen?

PW: I don’t know. I think it’s all tied up in legalities. And who cares about sequels, anyway? There’s only even been about two sequels that’ve ever worked. The Godfather is one of them, and Aliens is another one.

AVC: The Wrath Of Khan?

PW: The Wrath Of Khan… But, you know, I don’t know if that’s… I mean, you had a TV show before the movies, so that’s not really applicable. If you have a television series or a bunch of books to draw from, then you can go on with them forever and ever and ever. But to do a completely original sequel to a film? The good ones are few and far between.

Lou Grant (1977)—“Donald Stryker”

PW: That was… Wow, you’re bringing up some great stuff. [Laughs.] Okay, so I’m doing Streamers with Mike Nichols, a play that changed my life and one of the most remarkable pieces of theater ever. It would blow peoples’ minds. And then I get a call from my agent, who says, “You know, Allan Burns and Gene Reynolds of Mary Tyler Moore, they’ve started a Lou Grant series…” I said, “Look, I don’t want to do episodic television.” He said, “Look, they don’t just go around offering roles to actors in New York, but they saw you in Streamers and they want to fly you out… and nobody’s ever flown out from New York to be a guest star on episodic television! And it’s a true story. Why don’t you go research it?”

So I go to the library on Sixth Avenue and I researched it. It’s based on a true story about this Orthodox Jew who disappeared in his last month of high school and resurfaces four or five years later, six years later, with George Lincoln Rockwell, head of the American Nazi Party, in the state of New York. And I think some science editor for the New York Times found out about it, got a whiff of it, and under the auspices of interviewing the guy, met him at a café in Scarsdale and confronted him with it. The guy threatened him and started crying and begged him, then he threatened to blow up the New York Times building, and he finally killed himself in front of his church. So it’s a sad story of a kid who… I hate to say he was victimized, but he was, by his extraordinarily repressive grandparents and decided somewhere in his mind to not be the victim but to become the victimizer. It was a fantastic, well-executed idea, and I was very proud to have done the episode. And Ed Asner, I can’t say enough about him, or about Allan Burns, who went on to start my movie career by hiring me in Butch And Sundance: The Early Days.

Shakedown (1988)—“Roland Dalton”

PW: Shakedown. Gosh. Loved Sam Elliott. Loved making the movie. The thing is… Sidney Lumet taught me one thing: do not let the advent of the movie or the release of the movie or the success of the movie invalidate your experience of making the movie. He taught me that when I made Butch And Sundance: The Early Years with Richard Lester. I’d run around with horses, firing Colt .44s with black powder and all the stuff I grew up with, and Richard Lester was a dreamboat. We’re out in Colorado, the inland sand dunes at Alamosa, in Telluride and Santa Fe… and, you know, I come from west Texas, and here I am, 30 years old, living the dream, man. And then the movie doesn’t do so well. They take it away from Richard Lester, 20th Century Fox re-cuts it… [Sighs.] But then I met Sidney Lumet. The great Sidney Lumet… I mean, there’s a guy who schooled me. What a gifted filmmaker, and a huge mentor to me. He said, “How was the movie?” I said, “Well, you know, they did this, they did that…” He says, “I’m not asking you about what the studio did to your movie or what the world is going to think of your movie. What was your experience with the movie?” “It was wonderful!” “Then don’t let the physical result of the film, which you cannot control, invalidate your experience of making the film.”

So on that note, I had a great time making Shakedown, and then I was off to make Leviathan in Rome. Siskel and Ebert, they liked Shakedown, and I liked Shakedown, although I haven’t seen it since it came out, but then the movie did no business, so no one remembers it, which makes it easy to say, “Oh, it’s a mediocre movie.” Maybe I should go revisit. But I had a lovely time with Sam, I had a lovely time with James Glickenhaus, and I had a ball making the movie. And, by the way, it’s the only movie that shut down 42nd Street in its heyday of crack dens and hookers and porn shops. [Laughs.] When you walked down 42nd Street then, you needed an armed guard… and, indeed, Sam Elliott and I shot out there all night, and we had armed guards, because there was every sort of riff-raff and dangerous critter that you could imagine. It’s the only time it’s ever been done. I think they paid a million dollars to do it. Wow. Shooting on 42nd Street all night long on a Saturday. That was a ball.

[pagebreak]

Leviathan (1989)—“Steven Beck”

PW: You know, I’ve got to see that movie again, because a friend of mine just told me that it was highly entertaining. And I really liked working with George Cosmatos, although he is as mad as a hatter. [Laughs.] And I had the time of my life working in Rome for three months during the summer of ’88. It was an absolute… well, actually, I’m finally getting a Ph.D because of all that stuff! But I haven’t seen the film in… shoot, man, 25 years. I haven’t seen it since it came out.

AVC: It holds up pretty well. I think it got slightly short shrift from audiences because it and DeepStar Six and The Abyss all came out right around the same time.

PW: Yeah, that’s right, there were three of them. But I have to say, I did see a scene recently, just quickly, of the effects of the underwater stuff, and George Cosmatos’ idea of walking around and stuff floating by is really terrific. They didn’t go underwater. They did it in a studio in Rome.

AVC: You said he was mad as a hatter. Do you have a definitive George Cosmatos story?

PW: I have no definitive George Cosmatos story. I just loved him. I did two movies with him. He had great taste and a big passion for history and art. But he would be impatient enough sometimes to call “action” before sound was rolling… or the actors were ready or the cameras were even rolling. [Laughs.]

RoboCop (1987) / RoboCop 2 (1990)—“Officer Alex J. Murphy / Robocop”

PW: It’s certainly the most challenging role I’ve ever done. To bring that alive, much of it is thanks to Moni Yakim [the head of the Movement Department at Juilliard], Moni Yakim, the writers [Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner], and Paul Verhoeven. That quadrant of people all infused to make that thing, and Rob Bottin, the makeup artist, and Stephan Dupuis, the guy who put on the prosthetics. I dunno, that was just… I knew I was making a good film. When I met Paul Verhoeven in a hotel room in New York, I knew that, because Paul was directing it, it was going to be great. I knew it was going to have something of a moral opera in it and that he was not going to miss the universal morality in this. He was not going to just make an action movie. And it’s a very funny movie and a brilliant sort of social commentary. When I met Verhoeven, I’d seen all his movies, and I just knew he’d be fantastic. And to be feeling the feelings I felt when I met him… I mean, he was intimidating, but I knew that, with his expertise, he’d be executing something non-ephemeral and awakening certain aspects of social morality that’ll last. That movie will be around forever, man.

AVC: Does RoboCop 2 have anything to do with your general feelings on sequels being inferior?

PW: Yeah. RoboCop 2 didn’t have a third act. I told the producers and Irv Kirshner up front, and Frank Miller. I told them all. I said, “Where’s the third act here, man? So I beat up a big monster. In the third act, you have to have your Dan O’Herlihy. Somebody’s got to be the third act.” “No, no, the monster’s going to be enough.” “Look, it’s not enough!” When you have a movie like the first RoboCop, where the bad guys are never the bad guys and it’s always the morality of the thing. You know, like the idea that progress in the name of progress can steal a man’s identity. Look, the first RoboCop’s got deregulated trickle-down social economic politics in it, way before Bush and Romney and the debates with Obama and Senator Clinton. It’s got a morality to it. If you don’t have that, man, you’ve got no flick, and I said that so much. But, look, I don’t need to be right about RoboCop 2. I had a good time making Robocop 2. I was breaking up with a girlfriend at the time, so I can’t say I really had a great time, but I had a good time with Irv Kirshner, God bless him, and being in Houston, running around with Billy Gibbons of ZZ Top, who’s an old friend. But the script did not have the code, the spine, or the soul of the first one.

Screamers (1995)—“Joe Hendricksson”

PW: I don’t read them avidly, but of all the science-fiction writers I’ve encountered, Philip K. Dick, he’s separate. He wrote Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?, which became Blade Runner. He wrote Total Recall. His whole thing about slavery… I believe that Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? is actually based on Confessions Of Nat Turner, and Nat Turner was a true story of a slave that William Styron, who wrote Sophie’s Choice, wrote a book about. I think it won a Pulitzer. But it’s about a slave who escapes from… South Carolina, I think? And he kills people on a swath to get somewhere. It takes place in the 1830s or 1840s, and they can’t imagine what he’s doing. They don’t understand that he’s looking for his freedom. And that’s the basis of Blade Runner. We’ve infused consciousness into what we think are robots, and they’re just slaves, but now they want to live. That’s Philip K. Dick. And that’s, like, heavy stuff, man.

But “Second Variety,” which was turned into Screamers, turned into a corporate competition rather than a Russian/American competition. Once again, we built these machines that are essentially taking over a planet. In an aesthetic that lends itself to Zen or Eastern mysticism, there is no duality between subject and object. If you make this object, it has your consciousness in it, and you can destroy it as well. It’s all a dream. And it’s hard to tell that to a guy in Omaha who’s fighting to keep his house after he’s lost his job, but you make a chair, you’ve made that with your mind, and you can also destroy it with our mind. All you need is a nuclear bomb test to see that everything we’ve made out of our minds is ephemeral and can go. And Philip K. Dick was tapped into that one, man. The director, Christian Duguay, was fabulous, the cast was fabulous, and I just had an amazing time doing it.

There’s two moments in my film history—and I’ll give them to you right now—that have just been wildly, psychotically enjoyable. One was doing the drug-bust sequence in RoboCop, because the Walkman had come out, so you had these little earphones that you could put in the RoboCop helmet, and I was playing Peter Gabriel’s “Red Rain” during all the gunfire. Me with the 47-shot Beretta automatic pistol, blowing bad guys off balconies and stuff while “Red Rain” was pumping in my ears. [Laughs.] But the other moment was on Screamers. We had to approach this abandoned mill where the bad guys are, and it’s about a hundred yards of snow, and they had to shoot it once, because they had four cameras set up. I think I had to fire a machine gun once in awhile just to clear the area. But I had Soundgarden’s “Fell On Black Days” just jacked while I was walking across that blinding snow for a 10-minute shot. It was absolute heaven. These are the perks of making movies, man.