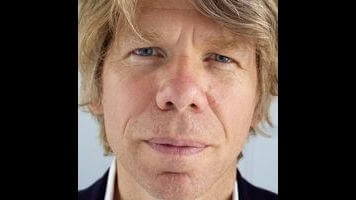

Petty is a candid, compelling portrait of an elusive rock legend

In spite of numerous hits that have kept him in the rock pantheon since the late ’70s, Tom Petty hasn’t been the subject of a major biography—not counting Peter Bogdanovich’s four-hour documentary from 2007, Runnin’ Down A Dream. Warren Zanes helped put together the book of the same title that accompanied the film (as well as briefly appearing in it), and now he’s taken a crack at penning that long-awaited major biography: Petty.

Access is not an issue. In addition to the Bogdanovich connection, Zanes’ band The Del Fuegos toured with Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers in the ’80s. That said, Zanes is careful not to let the book become a megaphone for whatever its subject might want to say; instead Zanes crafts a strong, studiously detached narrative that wends from Petty’s troubled youth in Gainesville, Florida, in the ’50s and ’60s to his conquering of the pop charts in the ’80s (with his band, as a solo artist, and as a member of the Traveling Wilburys) to his emergence in the 21st century as one of rock’s most beloved and enduring figures. It’s intimate—interviews with Petty as well as friends and family form a huge portion of the book’s substance—but Zanes keeps a careful editorial distance that helps modulate his obvious worship of the man and his music.

In a way, that distance even makes sense. Intimacy is an issue with Petty, both in a real life and in his songwriting, and Zanes’ approach is wholly empathetic. Petty was abused by his alcoholic father as a child, and early on he developed a quiet, determined air that never really changed as he ascended superstardom. It’s not that Petty projects a humble demeanor necessarily; he simply doesn’t project much at all, preferring to let his music speak for him. Zanes explores that paradox: Here’s a musician whose songs are beloved by millions, to the point where classics like “American Girl,” “Free Fallin,’” and his duet with Stevie Nicks, “Stop Draggin’ My Heart Around,” have become part of America’s cultural fabric. But as close as people feel to Petty, he’s always been mysterious in his unassuming way. At one point Zanes describes Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers as “a tribe of introverts”—and a more succinct way of nailing Petty’s pensive storytelling, reclusiveness, and aloof charm has never been delivered.

One of Petty’s biggest reveals is the period in the ’90s when he—divorced from his longtime first wife Jane Benyo and at a low point in his career, both creatively and commercially—became addicted to heroin. Petty has been reticent about discussing this period of his life, which he insists is because he doesn’t want to glorify the use of drugs or become, as Zanes puts it, “another rock star with tales of excess.” His personal story of celebrity addiction isn’t all that remarkable, considering all the similar ones that have been passed down over the years, but it does unveil a new dimension of Petty that fans have longed to see: vulnerability, something that he can so poignantly expresses in his music but rarely shows in public. One of Petty’s most touching chapters details the 2007 reformation of Mudcrutch, the unsuccessful band Petty played bass in back in the early ’70s, just before The Heartbreakers took the world by storm. Reunited with his old friends—including guitarist Tom Leadon, brother of The Eagles’ co-founder Bernie Leadon—Petty’s decades of struggle and triumph, not to mention his attempts to balance his introversion with the demands of being a bandleader, a family man, and a friend, come into sharp focus.

Zanes breaks the fourth wall a couple times, and while that kind of authorial intrusion in rock biographies often feels gratuitous and self-serving, he does it to tasteful effect. One chapter, set in 1987, recounts the time Zanes’ band was the opening act for The Heartbreakers, and how he wound up at Petty’s Christmas party that year, awestruck to be hanging out with Petty’s good friend and fellow Wilbury George Harrison; another, set in 2006, details how Zanes came to write the book that the reader is holding in her hand. These chapters are brief and beautifully written, full of wisdom and reverence, but they serve a larger purpose: Like Petty as a whole, they tether Tom Petty, giving his elusive persona context while leaving his mystique intact. As well it should be.