Glancing down into the rubble of a collapsed building, Nelly Lenz catches her own reflection in a shard of broken glass and is shocked to discover that she doesn’t recognize the stranger staring back at her. It’s 1945, and Nelly, a Jewish chanteuse emerging from the living hell of Auschwitz, has lost her career, her family, and now her very appearance to the Nazis. The surgeons warned that the disfigured visage they reconstructed—a word of multiple meanings in postwar Germany—might look as unfamiliar to her as the bombed-out Berlin she’s returned to. But there’s really no preparing someone for the shock of unraveling rolls of bandages, only to find someone new waiting underneath. “I don’t exist,” is about all this traumatized survivor can stammer on first glimpse.

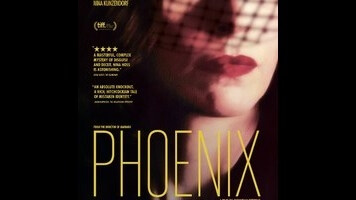

That face, so foreign to the character wearing it, belongs in our reality to Nina Hoss, willowy star of the new new German cinema. Phoenix is the sixth film Hoss has made with director Christian Petzold—the others include Jerichow and Barbara—and it’s very much the culmination of their collaboration, rewarding the trust these two artists have placed in each other. Conflating personal and national identity in the aftermath of the war, this classically efficient psychodrama nods to movie history without slavishly imitating it. For what it sets out to accomplish, across a brisk 98 minutes, Petzold’s film feels perfectly judged. And it builds to an ending that’s just plain perfect.

Phoenix belongs to a sterling tradition of postwar noirs, in which thick shadows envelop the ruined remains of once great cities and the living live with what they had to do to stay that way. (The film would pair well with The Third Man, which is still creeping its way across the country on a restored DCP.) Blessed/cursed with a new life and a new face, Hoss’ heroine shares an apartment with her friend Lene (Nina Kunzendorf), who toils away in the Hall Of Jewish Records, cataloguing the dead; a whole different movie could be built around this jaded supporting figure, cut from the same cloth as Agata Kulesza’s character in Ida. Lene is convinced that Nelly’s husband, a pianist named Johnny, sold her out to the Nazis to secure his own freedom. But Nelly, desperate to reclaim something she’s lost, goes looking for him anyway.

The search leads to the title establishment, a nightclub in the American sector whose neon sign casts a supernova of blood-red light. (Per its title, the joint can be read as a symbol for Germany itself, reborn from the ashes. Petzold, thankfully, doesn’t belabor the point.) It’s here, at the Phoenix, that Nelly is reunited with her husband, a haunted hustler played by Hoss’ Barbara co-star Ronald Zehrfeld. But rather than recognize his estranged spouse, Johnny sees only a woman who looks vaguely like her. And so he hatches a scheme: This apparent stranger will masquerade as his presumably (but unverifiably) dead wife, allowing him to claim the family inheritance she’s owed. This puts Nelly in the very strange position of taking tips from her own husband on how to look, sound, and behave more like the woman she used to be.

There’s more than a touch of Vertigo to the scenario, and fans of that Hitchcock classic will get a rush of déjà vu watching Johnny coach Nelly—stowed away in a dingy love nest below ground—on the proper way to walk in her favorite heels or do her hair and makeup. But Phoenix makes ingenious, psychologically complex use of this familiar premise. Johnny, whom Zehrfeld lends a weary brutishness, willfully refuses to see the truth under his nose, even as Nelly stops just short of blurting it out. For her, this perverse role-playing exercise is in part a way to determine if Johnny really did betray her. But in slowly conforming her appearance to his memories of her, Nelly is also chasing the ghost of her old life. (“I know he loves her,” she tells Lene, emphasis on the dissociative her.) Hoss, an actress of old-school glamour and modern nuance, has spent a career playing women with double lives; to look upon her piercing baby blues is to see two sets of turning wheels, one concealing the other. But Phoenix applies that gift for subtle deception, for performances within performances, to a true identity crisis—the role of someone forced to impersonate a stranger impersonating herself.

There’s another, more troubling dimension to the film’s high-concept plot, as Johnny isn’t just instructing Nelly on how to play herself, but also on how to believably portray a Holocaust survivor. “They want Nelly, not a ragged camp detainee,” he coldly replies when she insists that real Auschwitz prisoners don’t emerge looking like dolled-up nightclub crooners. But he’s right, in one sense: No one wants to be confronted with the specter of Hitler’s atrocities. Phoenix lays eyes on a Germany already slipping into denial, replacing the stark realities of what it sanctioned with a fantasy of restoration. The country, like Nelly and Johnny, wants to turn back the clock, but there’s no way to move backwards.

It’s a heavy freight for any film to carry. But if Phoenix is burdened by the weight of history, it never buckles: Petzold has made a expertly tuned genre piece, one whose pulpiness—guns, face changes, a danger-laced nightlife—doesn’t conflict with its more serious aims, and whose deep real-world resonance doesn’t compromise its dramatic economy. No scene is unnecessary. No shot is wasted. And then comes the last scene, the kind of punctuation that isn’t any less satisfying for feeling preordained, as though there was no other way the film could have ended. Phoenix knows just where to leave its audience. Its characters, pushing forward through a brave new world, aren’t so lucky.