Pixar got self-aware in Cars 3, a movie quite literally about selling out

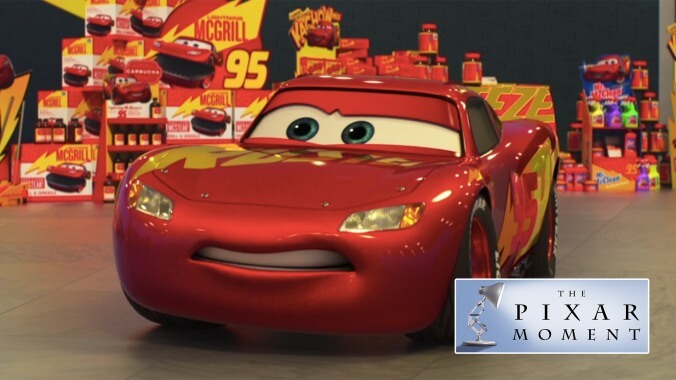

Image: Screenshot: Cars 3

“Every time you lose, you damage the brand.” It’s the best of Cars 3 and the worst of it in a single line.

The second sequel to 2006’s Cars is better than the second entry, but only due to it pushing Larry The Cable Guy’s grating Mater out of the driver’s seat. Owen Wilson’s Lightning McQueen again takes the lead, this time as an aging racer in fear of being left in the dust by a speeding caravan of millennial models. What follows is a kid-friendly riff on a Rocky sequel, one that doubles down on its predecessor’s longing for the racing days of yore by depicting the next generation as overconfident, technology-dependent bullies. In terms of Pixar franchises, the Cars series remains Goofus to Toy Story’s Gallant.

Yet Cars 3, oddly enough, is the only Cars film to veer into the orbit of what makes the Toy Story franchise so affecting. When Sterling, the billionaire sports car voiced by Nathan Fillion, backs Lightning, only to reveal he’s less interested in supporting his racing career than he is in licensing his image, Lightning is thrust into an existential dilemma. “I never thought of myself as a brand,” he says, gazing warily at the mess of mud flaps, McGrills, and protein powder buckets bearing his face.

Like Buzz and Woody before him, Lightning’s forced to consider what life looks like once he’s outgrown his usefulness. What does a racecar do when it can no longer race? And who gets to decide when you’ve crossed the finish line for the last time? The idea that it’s not you is heavy, and one of the sequel’s most affecting moments comes when Cal Weathers (Kyle Petty) solemnly says “the youngsters will tell you” when it’s time to stop. And they do, with hotshot Jackson Storm (Armie Hammer) leading the jeers against Lightning. And so does Sterling, who emphasizes the impact of each loss on the brand. Lightning, who believes “racing is the reward,” has to choose between his happiness and the value of his legacy. He has to choose whether or not to sell out.

The irony is that, for all the film’s fretting about authenticity, the Cars franchise is easily Pixar’s most commercial, the dips in its quality having correlated with an increase in sequels, TV spin-offs, and the adjacent Planes movies, none of which have done much for Pixar’s brand of smart, innovative animation. From their borrowed plots to their broad characterizations, the Cars films are the only ones on the studio’s lot to feel as if they’re pandering to their young audience, like they were built entirely by a focus group.

Granted, there’s a self-awareness baked into Lightning’s plight. The array of merchandise is a cheeky nod to the franchise’s toyetic nature, and Lightning’s commitment to “real racing” in the face of mass monetization could charitably be read as a promise, however hollow, to honor the franchise’s roots. But what resonates more is a persistent insecurity, and not only in the hand-wringing over the next generation. Cars villain Chick Hicks (Bob Peterson, taking over for Michael Keaton), here reimagined as a caustic sports announcer, feels like the manifestation of a bilious critic in his frequent antagonization of Lightning. And when Lightning tags in his young trainer, Cruz (Cristela Alonzo), during the final race, thus signifying a passing of the torch, it’s easy to read Sterling’s worries over the brand as a real-life anxiety. Will audiences accept a new protagonist? Cars 3 feels, at times, consumed by its perception. Pixar knows how Cars slots into its oeuvre, and doesn’t seem all too comfortable with it.

Of course, the franchise’s future is murkier than it once was. In total, the series has brought in more than $1 billion worldwide, but Cars 3 made a good chunk less than its predecessor, raking in $380 million against Cars 2’s $560 million. Furthermore, Cars was the pet project of gearhead John Lasseter, the Pixar co-founder who was pushed out of the Disney ecosystem last year following allegations of harassment. The third entry was the first to not feature Lasseter at the wheel, but it’s still likely his departure has put the brakes on another sequel. Leave it in the dust, we say. Enough gazing into the rearview. It’s not as if the franchise totaled Pixar’s brand, but the dents are nevertheless visible. Besides, we’re sick of wondering whether or not the cars fuck.