The rejection letter, as the late Mad magazine previously made clear, is an art form in and of itself. Having taken an author’s thoughts into consideration and found them wanting, the publisher must think up a way to say “nah” without, if they have any heart, being a total jerk about it.

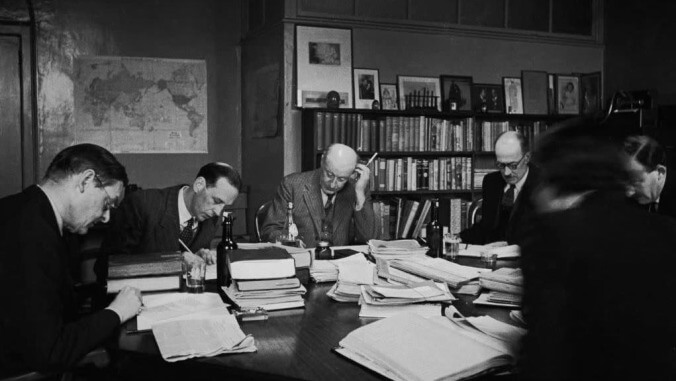

In a collection of famous rejections from UK publishing house Faber & Faber, assembled in an article at Literary Hub by its founder’s grandson, Tony Faber, we see this art demonstrated to varying effect by true masters of the form. Among them we see Faber, for various reasons, pass on everything from Animal Farm and Ulysses to the work of W.H. Auden and poor old Paddington Bear.

Most of those included are written by T.S. Eliot, who worked at Faber from the 1920s to the ‘60s. It’s him who, in 1932, tells a young George Orwell that Down And Out In Paris And London is “of very great interest,” but also “too short” and “too loosely constructed.” Later, in 1944, when the British were being very careful not to offend their Soviet allies, Eliot says Faber has to pass on publishing Animal Farm—and, by passing on Orwell again, missing a shot at 1984—because “we have no conviction…that this is the right point of view from which to criticize the political situation at the present time.”

Making up for the rejection somewhat, Eliot also tells Orwell that Animal Farm is “very skillfully handled, and that the narrative keeps one’s interest on its own plane” while adding his “regard for [Orwell’s] work, because it is good writing of fundamental integrity.”

In another example of a similar sort of judgement call, Eliot write James Joyce to say that Faber can’t publish Ulysses because censorship laws would likely lead to legal troubles, financial penalties, and “the possibility of the chairman’s having to spend six months in gaol, which in itself would be disastrous for the business.”

Elsewhere, Eliot tells W.H. Auden that a series of poems isn’t “quite right” but that he “should be very interested to follow your work.” (“By the time Auden died in 1973, the firm would have published something like 20 collections bearing his name,” Tony Faber notes.) Outside of Eliot himself, other Faber & Faber employees write notes that call William Golding’s Lord Of The Flies an “absurd & uninteresting fantasy,” “rubbish & dull,” and “pointless” (before reading further and eventually publishing the novel) and say Michael Bond “has missed the mark” with A Bear Called Paddington.

Considering the fate of every one of these authors and their work, it’s pretty heartening to read the various ways in which their landmark works of literature were passed over. To buck up your own creative spirits a little further, read the full article.

Send Great Job, Internet tips to [email protected]

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)