Poltergeist haunts every lame frame of The Darkness

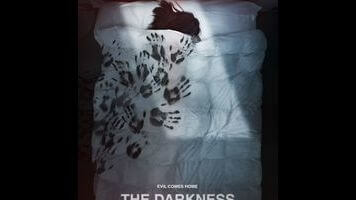

Greg McLean is the new Tobe Hooper. The evidence is piling up faster than the bodies do in either man’s movies. McLean, an Aussie director who got his start back when the term “torture porn” was at peak overuse, made a name for himself with Wolf Creek, the most harrowing hick-horror rampage since, well, Hooper’s original Texas Chain Saw Massacre. For an encore, McLean then made a film, Rogue, about tourists devoured by a giant crocodile—which, of course, is also the plot of Eaten Alive, Hooper’s follow-up to his own brutal breakthrough. And when it came time to make a belated Wolf Creek sequel, what did McLean do but go bigger, gorier, and crazier, just like Hooper did when he finally got around to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2. Now comes The Darkness, which officially ushers the younger director into his Poltergeist stage, complete with a suburban family harassed by spirits, a disrupted Native American burial ground, and a little kid drawn to a permeable portal between worlds. All that’s missing are the scares. Where’s a creepy clown doll when you need it?

In all fairness, a great deal of the supernatural horror movies made over the last 30 years owe a debt of influence to Poltergeist. Where these imitations distinguish themselves is in the real-world stuff the ghosts are representing and/or exacerbating. The Darkness has enough of that for five Blumhouse productions. The film begins at the Grand Canyon, where young Michael Taylor (David Mazouz, who plays pipsqueak Bruce Wayne on Gotham) falls into a hidden Anasazi sacred space and swipes some shiny, engraved stones, accidentally freeing pissed-off apparitions in the process. Okay, so the film’s really about white folks encroaching on native lands, right? Wrong! Turns out Michael is autistic, and that his sometimes erratic, inscrutable behavior has put a strain on his family. Mom (Radha Mitchell) is an alcoholic. Dad (Kevin Bacon) has a history of adultery. Big sister (Lucy Fry) is bulimic. The house, in other words, is plenty haunted before the unruly new tenants move in.

This is not, to say the least, the most nuanced depiction of autism or the challenges of raising a son with a developmental disorder. Michael is granted less personality than the walking-metaphor star-child from Midnight Special; McLean sometimes exploits his lack of affect to give audiences the willies and other times utilizes it as an easy answer to the eternal question of why a spooked family wouldn’t accept their spectral circumstances sooner. (Someone is creating sooty handprints on all the walls and blankets? Must be Michael. He is autistic, after all.) Mostly, the kid behaves how every kid does in one of these films, making “imaginary” friends with the spirits (can we have a moratorium on this cliché please?) and keeping his cool even as Mom and Dad lose theirs. Those wondering how his disorder possibly relates to ancient tribal spirits, never fear: Both parents eventually plug that inquiry into a generic search engine, pulling up a flatly expositional YouTube video on the topic.

It’s vaguely endearing to watch Bacon and Mitchell actually try to act their way through the film’s family drama, as though it weren’t a perfunctory pretext to jump scares. The Darkness needs their chops. It needs anything to distract horror fans from the fact that there’s nothing new here—not the pets that can smell the trouble, not the doorway to the other side, not the expert exorcist type consulted in act three. McLean, sad to say, just kind of disappears into the material; only the opening scene, which makes Arizona look as vast and foreboding as the Outback, bears his imprint. It’s possible he couldn’t do much of anything with these PG-13geists, whose supernatural gimmick (look out, they might finger paint on you!) isn’t terribly frightening. On the other hand, maybe McLean, like Hooper before him, just needed a Steven Spielberg looking over his shoulder. These ghost stories don’t ghost direct themselves.