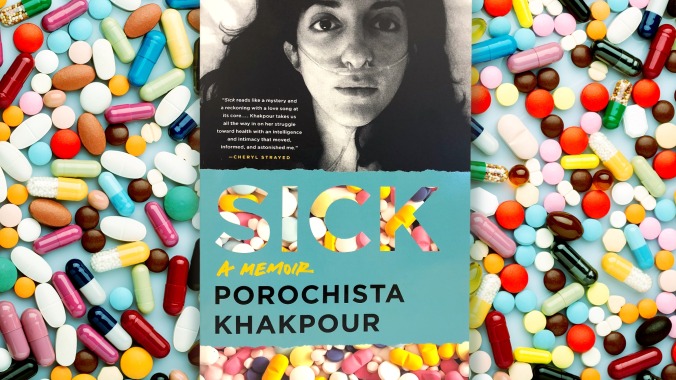

Porochista Khakpour writes illness as memoir in Sick

Porochista Khakpour has been sick her entire life, tormented by pain, mental and physical. She suffered from tremors, depression, and fainting spells as a kid. Panic attacks and insomnia in her 20s. Joint pain and muscle aches, chronic lethargy and serious anxiety in her 30s. The obstinate feeling that her body is not her own to inhabit has endured throughout. “As I child, I thought of myself as a ghost,” she writes early on in her memoir Sick, “an essence at best who’d entered some incorrect form.”

Khakpour blames her illness, at least in its current form, on Lyme disease, a tick-borne infection that attacks the body’s soft tissues, resulting in fever, severe headaches, fatigue, joint pain, and cognitive malfunctions, among other ailments. Problem is, the existence of patients with “chronic” Lyme is largely rejected by the medical establishment, including the Infectious Diseases Society Of America and the Centers For Disease Control And Prevention. Lyme, she writes, is the malady of “hypochondriacs and alarmists and rich people who have the money and time to go chasing obscure diagnoses.”

At times, Sick reads like a House-ian medical thriller. Did Khakpour contract Lyme during a family hike in the Angeles National Forest at the age of 5? While vacationing in the Hamptons with a boyfriend? During a ramble through the woods while teaching in eastern Pennsylvania? She’ll likely never know. In the end, it doesn’t really matter.

The daughter of upper-class Iranians-turned-Los Angeles enclaved exiles of the 1979 Revolution, Khakpour lives the life of an alien many times over: a brown woman dislocated in white America, an individual dispossessed from her own body, a patient estranged from the medical establishment. Women with Lyme disease suffer the worst, she points out. Doctors often treat female patients as psychiatric cases first—a remnant of the era when medical authorities used “hysteria” as a catchall diagnosis—allowing acute, antibiotic-treatable tick bites to advance.

For years, her condition likewise goes undetermined. Internists and nurses laugh at her, call her crazy. Friends and physicians blame a nightmarish litany of diseases, from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to lupus to diabetes to Parkinson’s, Hashimoto’s, and various cancers. She’s prescribed a rainbow of pills: Ambien, Ativan, Celexa, Klonopin, Neurontin, Paxil, Remeron, Seroquel, Xanax. She tries nutritionists, acupuncturists, ayurvedics, and other new age healers, spending over $140,000 on her well-being.

All the while, Lyme lurks in the shadows, inescapable. She watches a boyfriend’s mom slowly deteriorate from the disease, and even unknowingly adopts a Lyme-stricken dog. Her relapses coincide with turmoil, both internal and external: loneliness, global terrorist attacks, a certain presidential election. “I am a sick girl,” she acknowledges. “I know sickness. I live with it. In some ways, I keep myself sick.”

Sick will not reward readers with a happy ending, though there are triumphs, large and small. Khakpour overcomes an addiction to benzos and finds salvation, of a sort, through bee venom therapy (the book is dedicated to “Voyce & her honeybees”). Her sickness is identified, she makes a point to tell naysayers, as a CDC-recognized case of late-stage Lyme. She fitfully publishes two novels; teaches creative writing classes at colleges around the world; dates charming men overflowing with caretaker promises and undiagnosed issues of their own. And in the end, she produces a book that might one day join the shelf of, for lack of a better term, sick lit classics, including The Bell Jar, Illness As Metaphor, and Brain On Fire.

Total wellness will never come for Khakpour. The U.S. healthcare system—ranked last among the world’s 11 wealthiest nations according to a 2017 report—will continue to fail her, and each and every one of us. According to her Twitter feed, she is currently in the midst of another relapse. There are medical bills and a book tour to pay for. Lyme deniers and truthers to debate. Hopefully, more novels to write, students to teach.

Midway through Sick, Khakpour writes of an acupuncturist who compares her then undiagnosed illness to a sleeping dragon that periodically, wrathfully awakens. “But what is it?” she asks. The acupuncturist shrugs, “Does it need a name?”