The essential beginners’ guide to Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Springsteen 101:

The Jersey-bred Springsteen started gigging around his home state beginning in 1965, first as the 16-year-old wunderkind guitarist in a garage-band called The Castiles, and later, at the end of the decade, as a shaggy-haired guitar hero fronting the heavy blues-rock outfit Steel Mill. Throughout Springsteen’s early adventures in clubbing—which included at least three more band names and countless different line-ups—Springsteen seemed torn between the different styles he was both capable and interested in pursuing. Part of him wanted to crank out hooky hit records, like The Rascals. Part of him wanted to grind through long jams, like The Allman Brothers. And part of him wanted to be Bob Dylan, telling rambling stories about colorful characters over rickety electric folk music. His Dylan side had won out by the time he landed a record deal with Columbia in 1972—the label even took out ads dubbing him “the new Dylan”—but his commercial and creative breakthroughs would come later in the decade, when he learned to eschew clever wordplay and just sing direct songs about relatable topics.

If any one song encapsulates Springsteen—his indelible melodies, his gripping storytelling, his grasp of emotional and cultural detail—it’s “Atlantic City,” a morose crime story debuted on the stark 1982 folk album Nebraska. Populated by the kind of colorful characters that haunted Springsteen’s early albums, yet steeped in the working-class anxiety that started to take hold around 1978's Darkness On The Edge Of Town, “Atlantic City” begins with a general report on mob violence and ends with one hard-up mug taking a job that’s bound to get him killed. Springsteen sells the song with his croaky, committed vocal and small lyrical gestures (like when the narrator, kindly to the last, tells his girl to “put on your stockings, ‘cause the night’s gettin’ cold”). And then there’s that chorus, so spooky and unduly hopeful: “Maybe everything that dies some day comes back.”

“Atlantic City,” for all its atmosphere of despair and danger, is a love song, and it’s in the love song format that Springsteen has been easiest to like—even when he bends the concept a little. “Two Hearts,” from 1980's The River, is an exultant paean to the concept of couplehood, and though it ends with an admission that the singer is alone—but looking, always looking—The E Street Band’s relentless drive elevates a simple plea for togetherness into something epic and eternal.

“All That Heaven Will Allow,” from 1987's Tunnel Of Love, is a much lighter song: ebulliently poppy but not cloying. It’s another declaration that love is all our man needs, but this time, he’s holding onto something he’s already got, and describing how confident it makes him feel to have a steady. After writing that song, Springsteen went through a divorce and remarriage, then wrote “If I Should Fall Behind” for 1992's Lucky Town. The singer’s recent history of loss and rejuvenation informs the song, which is filled with poetic imagery of beautiful rivers and oak boughs, and lovers who fall out of step. “But I’ll wait for you,” Springsteen half-whispers, “And if I should fall behind, wait for me.”

In the above four songs, there’s something serious at stake. But in “Cindy,” an aspiring boyfriend makes a series of halfhearted attempts to court the object of his infatuation and keeps getting rebuffed, in almost comical fashion. “Cindy” was slated for the original single-disc version of 1980's The River—known then as The Ties That Bind—and it remains the only song from that record that didn’t make it onto the final album or any of the official Springsteen leftovers collections. It’s a slight song, but endearingly so, and it showcases Springsteen’s gift for throwaway pop numbers—a direction he could’ve gone in had he chosen to be The Rascals instead of Dylan. And yet the song is no throwback. Listen to “Cindy”’s shimmering guitar bridge, which was recorded in 1979, yet anticipates the just-around-the-corner Britpop sound of bands like The Smiths and Aztec Camera.

Intermediate work:

After Springsteen signed with Columbia, he recorded Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ, a lyric-stuffed quasi-boogie record with a lot of songs that showed promise—including one, “Blinded By The Light,” that became a #1 hit in a prog-rock arrangement for Manfred Mann’s Earth Band—but the overall sound was too derivative and amateurish, and nothing like the raucous rock-and-soul revues he and his newly dubbed “E Street Band” were starting to perform to packed clubs up and down the East Coast. Springsteen really announced himself as an original on album number two, The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle, released in late ‘73 (roughly nine months after Greetings). With songs like “Rosalita” and “Incident On 57th Street” pushing past the seven-minute mark, The E Street Shuffle allowed Springsteen to explore different moods—from slapstick to serious—within the same song, and also let him show off his crackerjack bandmates.

Throughout his career since, Springsteen has tried to recapture that sprawl, in songs that spread across landscapes and drag handfuls of lost people along in their wake. (It’s this style that’s proved inspirational to modern rock bands like The Hold Steady and The Arcade Fire.) Sometimes these songs run long, and sometimes Springsteen keeps them compact. During the sessions for The E Street Shuffle, Springsteen recorded (and eventually abandoned) a few vamp-y songs that had been road-tested and audience-approved, and a few garage-rock exercises that didn’t fit the style he was exploring at the time. “Seaside Bar Song”—eventually released on the box set Tracks—is one of the latter, rocking a tinny organ, a Duane Eddy guitar riff, and a bleating sax, all as if The Beatles never happened. The song features a yearning break in the middle and a few other oddball touches in the arrangement that mark it as a product of the ‘70s, not the ‘50s, but the propulsive sound and vivid road imagery help connect the music Springsteen grew up on to the music he was about to make.

“Thunder Road”—and the entirety of 1975's Born To Run album—picks up where “Seaside Bar Song” left off, exploring the inner lives and anxieties of people who cruise the night in souped-up Chevys. “Thunder Road” builds from a tinkling piano and images of screen doors and wind-blown hair to a promise of escape, set to music that chugs, rumbles, and pulls away in triumph. It’s the apotheosis of the “young Springsteen” style, and ground zero for his next stage.

Springsteen has said that writing Born To Run’s songs on a piano finally let him realize the sweeping “golden oldies grow up” vision he’d had for his music from the beginning. But his early songs still come to life in the right context, even with a guitar carrying the bulk of the load. The Greetings From Asbury Park version of “It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City” sounds as muffled and crazily loquacious as the rest of that album does, but the version on Live 1975-1985—recorded at the Roxy in 1978—gets all the cockiness and menace that had always been intended. The dueling Springsteen and Steve Van Zandt solos that close the performance sum up the time and place described in the song better than the lyrics’ overheated metaphors.

Springsteen has always done “summing up” remarkably well, which speaks to his faith that the right song at the right time can transform people. Toward the end of the sets during The E Street Band reunion shows of 1999 and 2000, Springsteen played “Land Of Hope And Dreams” (available on Live In New York City), a pastiche of “People Get Ready” and “This Train Is Bound For Glory” that linked up Springsteen’s mutual love of R&B and folk music, and presented his version of an America built to carry all passengers.

But the ultimate valedictory song in his repertoire is “4th Of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” from The E Street Shuffle. The overwrought, overstuffed descriptions of the previous album give way to a more relaxed tour of the boardwalk, as Springsteen points out the carnies and hustlers that make Asbury Park so colorful and so sad. The beauty of the song—arguably the most beautiful song Springsteen has ever written—is the way the travelogue evolves into an argument. The narrator is getting ready to leave, and trying to convince Sandy to go with him. Does she say yes? Check “Thunder Road” for the answer.

Advanced studies:

The promise of The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle gave way to the commercial breakthrough of 1975's Born To Run, which tempered the youthful exuberance of Springsteen’s earlier albums with tighter song-structures and a little bit of the creeping working-class melancholy that has been the dominant subject of his songs for the last 30 years. In an era of surface-deep corporate rock, Springsteen’s direct, honest appeal inspired artists like Tom Petty and John Mellencamp to let go of the payola-and-coke-spoon star-track that both of them started out on, and try instead to make music about where they were from. Meanwhile, Springsteen’s Darkness On The Edge Of Town, The River, Nebraska and the blockbuster 1984 hit Born In The U.S.A. all reached an expanding audience with simple songs—many with hummable choruses—that describe how it is to live under the specter of divorce, unemployment, war and, worst of all, mediocrity.

Not for nothing did Springsteen first want to name The River after its leadoff song, “The Ties That Bind.” Along with community-defining anthems and tales of young love, Springsteen has written a large body of songs about family, responsibility, and the tangled legacies parents leave their children. One of the sweetest is “The Wish,” a Tunnel Of Love leftover dedicated to a mother who buys her son a guitar and gets a song in return. The loving memories of mom’s working clothes and the pleasure she took in dancing are among the most unabashedly happy in Springsteen’s songbook. At this very moment, “The Wish” is just waiting for some country star to cover it and make it a new standard.

But again, “The Wish” is pretty much an aberration. For a more typical Springsteen take on what happens to families and people in love, start with “Darkness On The Edge Of Town,” the title track of his 1978 album about broken promises and painful endurance. The song’s narrator has lost everything, for reasons only hinted at: “I’ll pay the cost for wanting things that can only be found in the darkness on the edge of town,” he sings, indicating that no matter how warm home and hearth may be, there’s something alluring lurking outside, drawing him away from what he knows is proper.

Perhaps that something is the stolen car of “Stolen Car,” which the song’s narrator drives because he’s hoping to get caught. “Stolen Car” has been released in two versions, both essential in their way: the murmuring, minimalist take from The River, and the country-ballad version that preceded it on The Ties That Bind. In both, Springsteen sings about the gap between youthful passion and middle-aged respectability. The narrator explains that they threw a party when he got married, and he’s certain that somewhere, they’re still partying without him. So he ventures out into the darkness, waiting for his sins to catch up to him and shut him away once and for all from the good life he isn’t living.

Then again, maybe all he needs is a good scare to wake him up. In “Wreck On The Highway,” also on The River, the narrator drives at night—just like everybody else in a Springsteen song—until he passes an accident scene, and a dying man. And he starts thinking, mainly about a woman who’ll never see her husband or boyfriend again. So now the narrator stays home nights, sitting up in his bed in the dark, staring at his own wife, and contemplating death.

Death also pervades “Gypsy Biker,” the best song on Springsteen’s latest album, Magic (a return to the E-Street-Band-fueled glory days of The River and Born In The U.S.A.). Over lashing guitars and pounding drums, Springsteen sings about a death in the family—possibly a military family—and what it means to the people left behind. In its performance alone, “Gypsy Biker” is one of the most intense songs The E Street Band has recorded since the Born In The U.S.A. era, but it’s also chillingly elegiac, as Springsteen sings, “To the dead it don’t matter much ‘bout who’s wrong or right.” In the past, Springsteen has been able to use the lives and deaths of others to recontextualize the protagonists of his songs. Here, the meaning is that there is no meaning. Just finality.

The essentials:

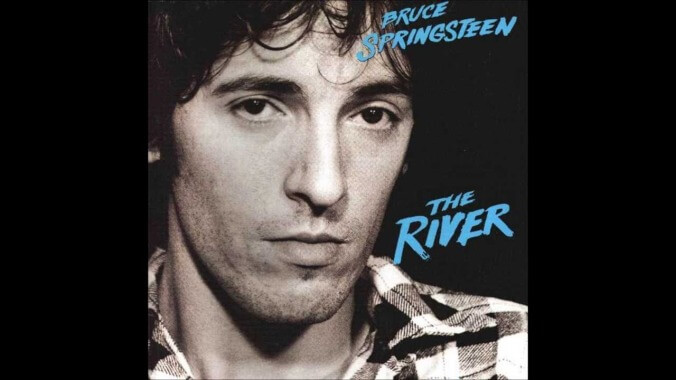

1. The River (1980)

Springsteen first met rock critic Jon Landau in 1974, and eventually made the scribe his friend, producer, and manager. From the start, Landau urged the ambitious young rocker to simplify, and to try to write songs more like the garage rock that was already a major component of The E Street Band live experience. After the long struggle to craft the grim Darkness On The Edge Of Town, Springsteen leaned heavily on his friend and guitarist Steve Van Zandt to help him bash out songs that were looser and less studied, and the result was a two-year burst of creativity that culminated in a double album. The whole of Springsteen is here: the pop, the frat-rock, the country ballads, the working-man’s sorrow, the horny teenager’s joy, the giddy humor and the life-changing realizations.

2. Born To Run (1975)

Springsteen’s first two albums sold poorly and were met with mixed reviews, to the extent that when his third album became a runaway success—with Springsteen making the covers of Time and Newsweek in the same week—some people questioned whether show-business chicanery was afoot. Actually, what happened was that years of touring and Landau’s brotherly advice helped Springsteen get as close as he’d ever get to the cinematic sound in his head, and in a rock market split between stoner pap and increasingly ethereal prog, Born To Run proved as revelatory as Jaws would be to moviegoers. It was the record people had been waiting for, and even now, it sounds thrilling and timeless, pumping with the blood of a thousand teenagers staring out of their windows at midnight.

3. Nebraska (1982)

Becoming alienated by the values taking hold in the Reagan era—both in the music industry and in the culture at large—Springsteen holed up in his house with a four-track and demoed a bunch of songs about murderers and poor folks. When he tried to turn them into a rock album, they didn’t work, so Springsteen released the demos, letting his fans fill in the wide spaces in Nebraska’s arrangements with their own ideas about what he was saying, where he was heading, and whether they wanted to follow.

4. The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle (1973)

Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ, was a minor misfire, conveying little of the high-spirited E Street rock carnival. And while the production on the follow-up The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle is just as muffled, the songs are among the most sprawling and inventive that Springsteen has ever recorded, jumping from the post-Cream blues boogie of “Kitty’s Back” to the Salvation Army band pump of “Wild Billy’s Circus Story” to the nothing-else-like-it adolescent mania of “Rosalita.” It’s a singular album in rock history and Springsteen history, and many of his longtime fans are still hoping he’ll return to its style someday.

5. Tunnel Of Love (1987)

Springsteen made the transition from star to superstar with 1984's Born In The U.S.A., then began to beat a retreat, by getting married, dismissing The E Street Band, and recording a low-key, curiously glimmering album about settling down, yet remaining discontented. Tunnel Of Love contains two of Springsteen’s best singles—the urgent title track and the sophisticated “Brilliant Disguise”—but the record expresses its theme best in its final song, “Valentine’s Day,” a semi-rewrite of “Wreck On The Highway” in which the narrator confesses that he clings to his wife more out of nightmarish terror than sweet reassurance. To date, it’s the last “great” album that Springsteen has made, though his reunions with The E Street Band on The Rising and Magic have proved that he can continue writing and recording relevant songs for as long as he cares to. Springsteen still has plenty of styles he hasn’t yet fully explored—some of which he pioneered.

Miscellany:

Two of Springsteen’s most popular songs were actually hits for other people. The Pointer Sisters turned the playfully smirky “Fire” into a pop and R&B smash, while Patti Smith and 10,000 Maniacs both garnered radio play with “Because The Night,” a simmering lust anthem that boils over dramatically. Springsteen has performed these songs in concert, but in some ways, they don’t really fit into the rest of his oeuvre; both sound like excerpts from albums he never made. (Although “Because The Night” would probably sound just fine on the heady Magic, oddly enough.)

“Light Of Day,” on the other hand, has become an essential staple of the Springsteen live show, where he uses it as a kind of altar call for the audience. It’s hard to believe now that the song started out as a fairly lame Joan Jett-sung title track to a clumsy Paul Schrader movie:

While Springsteen has been covered extensively, he’s also done his share of covering, most notably on last year’s We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions, which found contemporary relevance and a surprising amount of rock energy in traditional folk songs. One of the set’s highlights is Springsteen’s version of the dustbowl ballad “My Oklahoma Home,” which he sings as an elegy for the homes lost and people displaced after Hurricane Katrina, ending with a note of hope by pointing out that once your house is scattered to the four winds, your home is literally everywhere.

While touring behind The Seeger Sessions, Springsteen reinterpreted some of his old songs in a retro style that changed some of them for the better. The greatest beneficiary of the treatment was Nebraska’s “Open All Night,” formerly a slight roadhouse rocker, and now—as heard on this year’s Live In Dublin—a jump-jive/Western-swing workout. The debt Springsteen owes to his forbears has never been plainer, nor so happily repaid.