With Come, Prince said goodbye to his pop persona

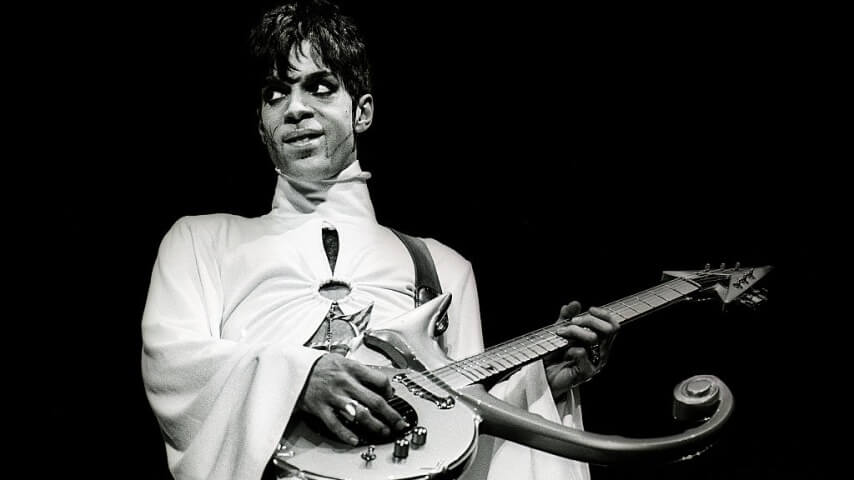

After his fifteenth album, Prince changed his name to a symbol

Prince intended Come, his fifteenth studio album, to serve as a farewell of sorts. Embroiled in an escalating feud with his record label Warner Bros., who he believed had restrained his creativity, he seized on a scheme that would free him from his constraints: he’d reinvent himself as a new artist—one whose name was an unpronounceable symbol, which he called the “Love Symbol”—and leave Prince in the past.

The cover of Come functions a bit like a tombstone. Prince stands in front of a gothic gate—in actuality Barcelona’s Sagrada Familia, looking far more imposing than it does in most pictures—scowling at the camera. Underneath his name are the numbers “1958-1993,” years representing his birth and the date he intended to put Prince to rest.

Warner wasn’t exactly happy with Prince’s plot, particularly since it hinged on the musician taking the recordings he made as The Artist Formerly Known as Prince (as he was called after he changed his name) to another label. They acquiesced to his wishes once, allowing Prince to release “The Most Beautiful Girl In The World” on his own NPG imprint only to see the Philly-soul tribute become a bigger hit than anything on his previous album, Love Symbol. Inspired by the success of “The Most Beautiful Girl In The World,” Prince decided to save his fresher material for an album he’d release as the symbol, leaving the older tunes for his final Prince album, Come.

Not that the music on Come had been laying around in Prince’s Vault for a long stretch of time. The album’s origin lay in a Christmas break jam session Prince held with drummer Michael Bland and bassist Sonny Thompson during the winter of 1992/1993, one that produced a handful of recordings, including the song that would become the album’s title track. Among these tunes was “Papa,” a startling, succinct snapshot of child abuse that Warner refused to release a single. Their rejection was the first domino to fall in Prince’s plan to sever his past from his future. By late April 1993, he announced that he’d fulfill his Warner contract with songs drawn from his Vault, a choice that also reflected his belief that the label didn’t properly promote Love Symbol.

Despite his public protestations, Prince found himself habitually unable to cease making new music. He embarked on a theatrical adaptation of Homer’s The Odyssey, titled Glam Slam Ulysses, writing new pop tunes as he labored to get the production off the ground. Some of this material was aired live onstage during 1993 but Warner chose to release Prince’s first compilation, The Hits/The B-Sides, instead of new recordings, further stoking the ire of the artist, even though he plucked two songs—”Peach” and “Pope”—from an early incarnation of Come for the collection.

The fact that Prince shuffled off a pair of tracks from the unreleased Come is a sign that his interest in the project was waning. New songs still arrived at a rapid pace but he started to save those lively numbers for another project, provisionally titled Gold, that would appear under his new unpronounceable name as a symbol, while Come would be released as a Prince record. As Gold came into shape, Prince handed in a version of Come to Warner in March 1994, one that no longer featured its title track. Vice President Marylou Badeux told Alex Hahn, author of the 2003 biography Possessed: The Rise And Fall Of Prince, “The company was so upset with that album. People said it was a piece of shit. There was a feeling that he was dumping garbage on us.” Claiming they didn’t hear a hit, Warner asked Prince to write a single and he obliged with “Letitgo,” a mellow soul number distinguished by a candied chorus. Prince countered the offer by stripping Come of anything resembling pop or rock, shuffling those off to the symbol album that was now titled The Gold Experience.

Prince hoped to release The Gold Experience and Come nearly simultaneously, which was not an unprecedented strategy in the 1990s. Guns N’ Roses released their two volumes of Use Your Illusion in the fall of 1991, while Bruce Springsteen released the twin records Human Touch and Lucky Town in March 1992. Still, Warner believed that between Prince’s own albums and the records released on his Paisley Park label, the market was oversaturated, so they declined the offer, choosing to release Come even though they weren’t satisfied with the end product.

The label wasn’t the only audience who found Come unfulfilling. Robert Christgau dismissed it, claiming “porn now an annoyance, funk still a surprise,” while Melody Maker’s Simon Price noted its crucial flaw: “This, the last recording under the name Prince, is apparently his parting gift to Warner: An album containing no feasible singles.” Opening with its epic eleven-minute title track, Come did not court a pop audience in the slightest, instead offering ten songs of carnal R&B culminating in “Orgasm.” The consistency is a bug, not a feature. While some cuts distinguish themselves—the frenetic electronic rhythms of “Loose!” feel tapped into a ’90s club zeitgeist, “Pheromone” works up some steam, “Dark” is an effective throwback slow groove—collectively, the album seems claustrophobic and monochromatic. It sounds like the work of an artist who has grown bored with his own creation.

Tellingly, Come was Prince’s first true commercial stiff. While Lovesexy just missed the Top Ten in 1988, Come entered the charts at 15, then stuck around for ten weeks before slipping away, never coming close to generating a hit single on the level of “Alphabet Street.” Prince retained his pop instincts, as evidenced by the expansive and colorful The Gold Experience, yet that was a temporary revival. Come did indeed serve as a closing chapter, bringing to a close Prince’s reign as an untouchable pop star. By the end of the 1990s, he’d been granted emancipation from Warner, which gave him the freedom to release whatever music he wished. The flood of recordings pushed him further from the spotlight, the culmination of a process that began with Come, the album where Prince attempted to kill the pop persona he came to see as dead weight.