There’s something about Princess Margaret that inspires Peter Morgan to think outside the box. He uses her episodes to indulge in new tones for The Crown—like a lush 1950s romantic melodrama or a brassy 1970s tragicomedy. “The Hereditary Principle” briefly feints towards being the latter, as Margaret and her man-of-the-month Derek “Dazzle” Jennings (The Souvenir’s Tom Burke) enjoy a raucous night of drinking, dancing, and gossip. But it turns out this episode isn’t just a repetition of last season’s stellar finale. Instead it evokes that hour to draw a contrast in how Margaret’s once glamorous life is slipping away from her. Dazzle isn’t there to woo her, but to inform her he’s becoming a Catholic priest. And the cigarettes that once seemed like her most fashionable accessory soon send her to the hospital for a lung operation.

“The Hereditary Principle” is a quiet, somber episode in which Margaret tries and fails to give her life new meaning as she heads into her mid-50s. And Helena Bonham Carter turns in not just one of her best performances on The Crown, but one of the best performances of her career. It used to be that Margaret would only occasionally let her icily confident mask slip to reveal the vulnerabilities underneath. Now she can only occasionally manage to put the mask up at all. Bonham Carter beautifully modulates her performance to highlight that shift without losing a sense of continuity with the old Margaret.

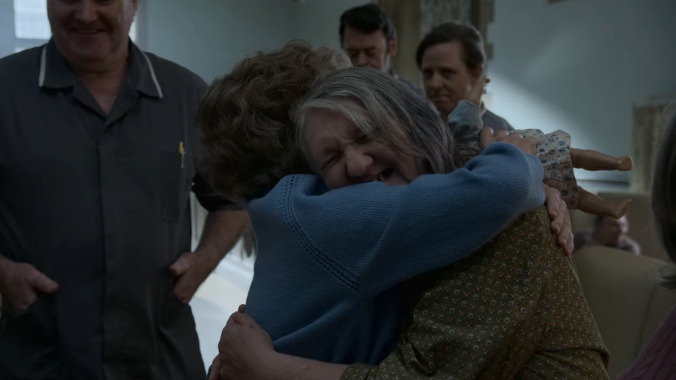

This episode also does a pitch-perfect job of capturing both the deep love and the inherent tension that fuels Elizabeth and Margaret’s relationship. Bonham Carter and Colman deliver some of the warmest, funniest sister scenes we’ve ever seen between the duo (their whole dynamic in the library is perfect). Yet as close as they are, Elizabeth still takes a business-like (if sympathetic) approach to informing Margaret of her new, lesser position within the family. With Edward turning 21, he now supplants Margaret as the sixth Counsellor of State—the senior royals Elizabeth can deputize on her behalf. That leaves Margaret more lonely and aimless than ever, sinking into a deep depression at her villa on the island of Mustique. But when Charles gently encourages his aunt to try attending therapy, she inadvertently discovers a new hobby to keep her busy: Amateur sleuthing.

“The Hereditary Principle” really has two aims. One is to deliver a bittersweet Margaret character study. The other is to shine a light on the lesser-known history of Katherine (Trudie Emery) and Nerissa Bowes-Lyon (Pauline Hendrickson), Elizabeth and Margaret’s first cousins on their mother’s side. The Bowes-Lyon sisters, along with three of their own cousins, were born with severe developmental disabilities and institutionalized for most of their lives. And—in The Crown’s telling of history at least—they were specifically hidden away and declared dead in order to avoid any potential negative associations with Elizabeth and her father.

For Margaret, the discovery of the family secret feels deeply personal. When the Queen Mother tries to explain that the situation is “complicated,” Margaret shoots back, “No it’s not! It’s wicked and it’s coldhearted and it’s cruel. And it is entirely in keeping with the ruthlessness I myself have experienced in this family.” The biggest problem with “The Hereditary Principle” is that while it effectively draws a parallel between Margaret and her cousins, it doesn’t do enough to highlight the contrast as well.

Yes, Margaret has experienced a lot of emotional difficulties due to her position as a royal. But, no, being a princess who can retreat to the private island villa that a Baron gifted you as a wedding present isn’t quite the same thing as being abandoned by your family and left in a mental institution in Surrey. The Crown doesn’t exactly suggest that they are. In fact, many of its shots purposefully contrast the glamour of Buckingham Palace with the much less glamorous environment of The Royal Earlswood Hospital. But because this episode is so firmly rooted in Margaret’s perspective, it ultimately winds up using Katherine and Nerissa as what amounts to props in her story. After Margaret has made her discovery, the sisters don’t even appear in the final third of the episode. We drop their story once it’s served its purpose in Margaret’s. And that makes this episode a sort of half step for disability representation.

Where “The Hereditary Principle” does succeed is in emphasizing just how much our understanding of mental disability and mental health has shifted in the past 35 years. Peter Morgan’s script makes a point of having the Queen Mother explain that “imbecility” and “idiocy” were the official medical terms used to diagnose Katherine and Nerissa, which is shocking to hear. And the show’s 1980s characters casually conflate mental illness and intellectual disability in a way that speaks to how limited the understanding of both were until recently. (Even going to therapy at all is seen as something of a drastic step for Margaret to take in the 1980s.)

Yet in presenting Margaret as a righteous defender of her cousins and a sympathetic victim of her family’s cruelty, “The Hereditary Principle” misses her complicity too. It’s absolutely horrifying to hear the Queen Mother make what amounts to a eugenics-based argument for shoring up the monarchy. But it’s also upsetting to watch Margaret discover this information about her family, passionately voice her disgust, and then do absolutely nothing to change Katherine and Nerissa’s situation—not even just pay them a visit, which clearly would’ve meant a lot to them given their pride in their connection to the royal family.

On the other hand, maybe I’m just not giving Morgan enough credit for his subtle critique of the pitiable princess. Margaret’s final conversation with Dazzle proves that for however much she might complain about her family, she actively chooses to remain a part of them too. She could have given up her royal title to marry Peter Townsend, just as she could now step away and become a Catholic. But being royal is the central defining principle of Margaret’s life and she can’t leave it behind—even if, technically, she can. If Margaret’s life is a tragedy, it’s a tragedy in which she still has agency and options. And that’s what ultimately separates her from her cousins.

Stray observations

- I loved that Elizabeth is the one to inform Margaret that her new would-be boyfriend is a “friend of Dorothy.”

- Philip notes that he and Elizabeth made the decision to have Andrew and Edward “after a tough negotiation on the yacht in Lisbon in a storm.” From what we already know of that conversation (which we saw in the second season episode “Lisbon”) that means Philip agreed to have more kids in exchange for Elizabeth making him a prince. Classic Philip…

- Again, Margaret’s point of view isn’t necessarily the point of view of the show itself, but the fact that she only deems Katherine and Nerissa’s institutionalization truly “unforgivable” after she learns their disability has no direct genetic tie to Elizabeth seems like the wrong takeaway.

- The Crown usually features its characters in such limited combinations that it’s almost jarring to remember that Margaret is Charles’ aunt and that they have a relationship of their own. (And a rather sweet one!)

- “Not everything that is wrong with this family can be explained away by the abdication!”

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)