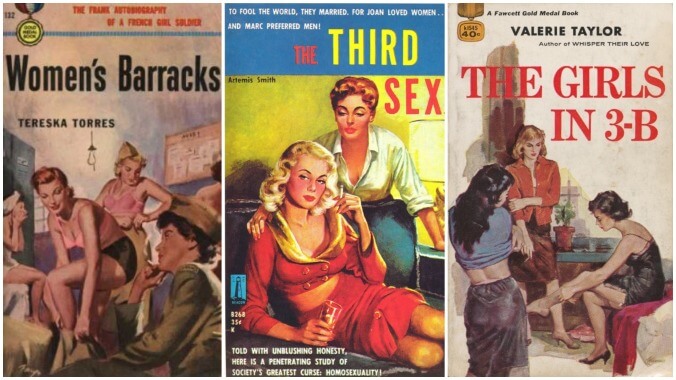

Biggest controversy: Congress moved to ban lesbian themes in fiction after just one book. Tereska Torrés’ Women’s Barracks, published in 1950, is considered the first paperback with lesbian characters. Torrés wrote based on her own experiences fighting with the Free French Forces in WWII, and her story was a runaway hit, selling four million copies. It also attracted the notice of the House Select Committee On Current Pornographic Materials. Congress immediately demanded publishers “conform to certain moral standards,” though publishers were quick to find their way around the decree. One popular method was to tack on a tragic ending for gay characters, so the books couldn’t be accused of promoting homosexuality. (This is almost certainly the origin of the “Kill Your Gays” trope.) A rare exception was Patricia Highsmith’s The Price Of Salt (which the 2014 film Carol was based on), which gave its central couple a happy ending.

Thing we were happiest to learn: Pulp novels also gave careers to a lot of lesbian authors. Fawcett, a magazine and comics publisher that created Family Circle, Woman’s Day, and Captain Marvel (the “Shazam!” one, not the Marvel Comics one) got into the paperback business in the ’50s, and made a point of hiring lesbian authors to write from experience, while most other publishers were hiring straight men “writing stories about lesbians for the titillation of other men.” (Fawcett was bought by Random House and absorbed by their Ballantine imprint in 1982.)

Thing we were unhappiest to learn: The genre was brought down not by censorship, but by the lack of it. By the 1970s, a Supreme Court decision protecting pornography from censorship meant the market was flooded with far more salacious material than suddenly-quaint-seeming pulp novels. At the same time, the rise of the gay rights movement meant that gay visibility wasn’t limited to dime-store novels, and those books’ most typical plot—two women in love in a world that refused to accept them—was becoming less and less relevant as acceptance of gay relationships gained a foothold in the wider culture.

Best link to elsewhere on Wikipedia: As you’d expect, pulp novels about gay men rose and fell in tandem with lesbian pulp. However, they were far less popular, as publishers marketed lesbian stories to straight men, often using titillating covers that had little to do with the content inside, while gay male pulps weren’t heavily marketed to women. But while lesbian pulp stayed pretty squarely in romance, gay pulp spanned numerous genres, including Westerns, war stories (A Different Drum was about a Union and Confederate soldier falling in love!), and detective stories and thrillers (Victor J. Banis’ The Man From C.A.M.P. was a series of nine books written in three years, about a James Bond-like superspy. The series was popular enough to spin off one of the first gay self-help books, an astrology guide, and a cookbook.)

Further down the Wormhole: Pulp authors are a good starting point for the far more extensive list of LGBT writers, whose listed works include fiction, essays, poetry, and history. Next week, we’ll look at a fascinating story from transgender history, that of Albert Cashier, a transman who fought for his country in the Civil War.