R.I.P. Christopher Tolkien, editor and steward of Middle-Earth

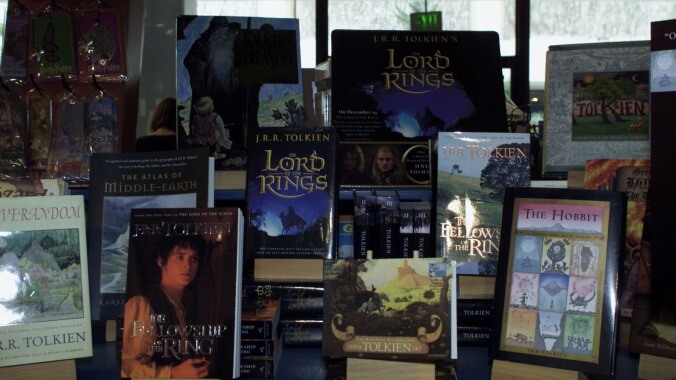

Christopher Tolkien has died. As both the literary executor, and the posthumous editor, of the works of his father, fantasy author J.R.R. Tolkien, Tolkien spent much of his life as the public face, steward, and occasional fierce protector of the fantasy realm of Middle-Earth. Over the course of his career, he was responsible for the publication of numerous works assembled from the elder Tolkien’s notes and uncompleted works, most notably The Silmarillion, which collected much of the early mythology and backstory of the beloved fictional world.

Born in 1924, Tolkien’s life and his father’s work were intertwined almost from the start; The Hobbit, at least according to some accounts, began as a series of bedtime stories told by their father to Tolkien and his siblings, before being expanded into one of the best-selling fantasy books of all time. As he grew into adulthood, Tolkien followed his father’s career path closely; an academic with an interest in fantasy cartography, he was inducted in his 20s into the Inklings, the informal Oxford literary society whose most prominent members included his father and his long-time friend, C.S. Lewis.

After J.R.R. Tolkien’s death in 1973, Christopher Tolkien spent much of the rest of his life organizing, editing, and publishing what remained of his father’s work—“what remained” turning out to be an absolute trove of wide-ranging material. His most prominent accomplishment was the publication of The Silmarillion in 1977, having assembled the massive tome from decades worth of drafts, notes, and—when needs must—his own written additions to connect and flesh out certain tales. The book itself proved mildly controversial, with fans of The Lord Of The Rings not especially happy with a “prequel” that was mostly semi-dry recitations of myths, and hardcore Tolkien wonks annoyed by certain choices and inconsistencies made in the editing process. And yet the book itself persists in the public imagination, buffered by later additions, including the 1980 Unfinished Tales and the 12-volume A History Of Middle-Earth.

In later years, Tolkien became perhaps best known for his reactions to Peter Jackson’s Lord Of The Rings films, an attitude that might best be summed up as “politely displeased.” (Up to and including reports that he was briefly estranged from one of his sons, Simon Tolkien, over his decision to support the films.) Not entirely surprising—given the time and energy he devoted, across his life, to the more literary aspects of his father’s work—he was reportedly unhappy with various concessions the films made to increase their pacing and action for the eyes of modern viewers. (Things got nasty enough in the 2010s that the Tolkien Estate sued Warner Bros., spurred on at least in part by their discovery of the existence of something called Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring: Online Slot Game, although both sides eventually settled out of court.)

Tolkien devoted much of his life to his father’s legacy, and to the fantasy universe that consumed so much of his creative life. And while Middle-Earth would persist, regardless of what came after The Return Of The King was published in 1955, Christopher Tolkien’s work ensured that fans of the first great fantasy world of the 20th century would never lack for new areas and angles to explore, new depths to immerse themselves ever more fully in. Every fan with a Quenya tattoo (or an encyclopedic knowledge of the various Ainur) owe him some debt of gratitude for his lifetime of service to their shared fantasy world.

Christopher Tolkien died this week; he was 95.