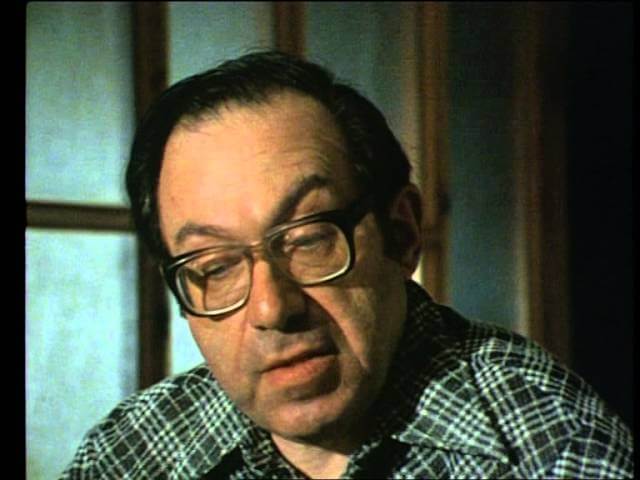

R.I.P. Claude Lanzmann, director of Shoah

The French documentarian and writer Claude Lanzmann, whose 1985 magnum opus Shoah stands as the medium’s definitive meditation on the Holocaust, has died. One of the greatest documentaries ever made, the nine-and-1/2-hour film took more than a decade to complete; it was the pièce de résistance of a long career. A disciple of the existentialist philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir (he had a long relationship with the latter in the 1950s), Lanzmann inherited the intellectual tradition of Paris’ post-war Left Bank literary scene, and was associated with the literary journal Les Temps Modernes for more than 65 years. He was 92.

Lanzmann was born in 1925 in Bois-Colombes, a Paris suburb, into a family of non-practicing Jews; his younger brother, Jacques Lanzmann, became a lyricist, best known for his writing partnership with the 1960s icon Jacques Dutronc, and also co-founded the French men’s magazine Lui. When France fell to German occupation, the family went into hiding at a farm in Auvergne. At the age of 17, Lanzmann joined the French Resistance as a member of a Communist group, unaware that his father, a World War I veteran, had become a leader in one of the main Resistance movements. While he continued his schooling using forged papers, the younger Lanzmann served as a machine-gunner in attacks on German convoys.

Following the war, Lanzmann studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. After a stint as a teacher in Berlin, he returned to Paris, where he soon got to know the major intellectual figures of the time, including Sartre and de Beauvoir. Though the two existentialist writers and philosophers were in an open relationship for most of their lives, de Beauvoir lived with the much younger Lanzmann from 1952 to 1959. They remained lifelong friends, and Lanzmann inherited de Beauvoir’s editorship of Les Temps Modernes after her death in 1986. He held the post until his death.

Lanzmann was a late bloomer when it came to film. Though planned as a smaller project, Shoah ultimately took six years to shoot and another five to edit; by the time it premiered, the director was 59. (It was only his second film, after the 1973 documentary Israel, Why?.) Shot on 16mm, it featured no music or archival footage, and tackled the enormity of the Holocaust with an immediacy that was by turns confrontational and haunting. Having cultivated a reputation as a globetrotter in his young years (his documentary Napalm, which premiered last year, dealt with his trip to North Korea in the late 1950s), Lanzmann travelled to 14 countries to conduct interviews, speaking to everyone from concentration camp guards and former Sonderkommando members to survivors and historians like Raul Hillberg, father of the functionalist school of Holocaust studies.

Some of the interviews were conducted under false pretenses, or even with hidden recording equipment, adding a layer of ‘70s paranoia to the proceedings—but then, as Lanzmann would probably argue, when the subject is an unprecedented moral catastrophe, journalistic ethics go out the window. Like so many of the greatest films, Shoah straddles contradictions. It’s a film about the past made entirely in the first-person present tense and a candid epic—filled with dimly lit rooms, trains, ruins, and faces in close-up—about bearing witness to something essentially unknowable: the horror of a mass atrocity. The interviews Lanzmann conducted in the 1970s produced hundreds of hours of footage, and some of the outtakes would eventually be edited into standalone features of their own, including Sobibor, Oct. 14th, 1943, 4 P.M. (2001), The Last Of The Unjust (2013), and his last film, The Four Sisters: The Hippocratic Oath, which was released in French theaters the day before his death.