R.I.P. Pete Shelley, of pop-punk pioneers Buzzcocks

Pete Shelley, the veteran singer and guitarist whose three decades with influential British band Buzzcocks helped bridge the worlds of punk and more traditional pop with his lively, wry takes on sexuality and love, has died. Shelley reportedly died of a suspected heart attack, and was 63.

Shelley (born Peter Campbell McNeish) was a college student in 1976, when he and fellow musician Howard Devoto caught wind of the first performances by a then-nascent Sex Pistols. Enthralled, Shelley and Devoto (plus drummer John Maher and bass player Steve Diggle, who’d be Shelley’s musical partner for most of his professional life) brought the punk pioneers to play at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, opening for them at a concert that was a) the first public debut of Buzzcocks, and b) destined to go down in legend as the moment the punk movement truly burst into life.

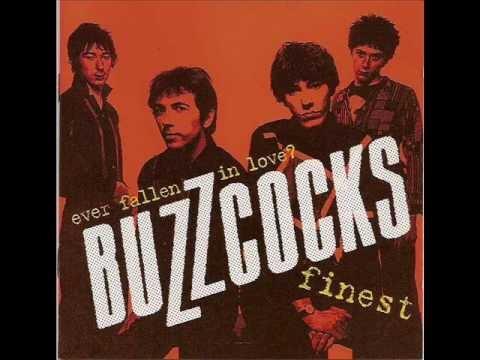

Throwing themselves into the music, and the scene, the band—minus Devoto, who left after the recording of a four-track EP, Spiral Scratch—quickly carved out a space for themselves in the punk scene, with Shelley’s high-pitched voice, sense of humor, and willingness to forgo self-serious political commentary in favor of more teen-relateable topics like heartbreak and other romantic miseries helping to distinguish them from the rapidly evolving pack. In the period between March 1978 and September 1979, Shelley and company managed to record and release three albums—including hit singles like “What Do I Get?” and “Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)“—while also touring extensively throughout Europe. And then they broke up.

Here’s Shelley on said collapse (and how he matured away from such similar attitudes as his career progressed), from an interview he did with us back in 2010:

When you start off, the market goes up and then they’re happy; when the market goes down, then they panic. So it’s a bit like that with the stocks and shares of having a band. When you start out and you have initial success you think, “Oh, this is great. We can do anything we want.” And then you get bad reviews and then you think “Oh no, the whole world is falling apart.” But after time, you get used to the ups and downs. It’s a bit like the seasons. I mean, looking back, we realize the volume of work we’ve got. And so now we can enjoy it! [Laughs.] It’s far more enjoyable, because you get to realize what its true value is, and you feel less exposed and vulnerable.

Moving away from the punk movement for a time, Shelley instead embraced an earlier love: electronic music. After releasing a pre-Buzzcocks album (Sky Yen) in 1980, Shelley made his fresh solo debut with 1981's Homosapien, which grew out of sessions he’d been recording as Buzzcocks’ fortunes began to wane. Synth-heavy and in love with drum machines, the album was a bold departure for Shelley, one that has eventually been seen as the strongest solo effort of his career. Its title track also got him a ban from the BBC, uncomfortable with lyrics referencing his bisexuality. (Or maybe they just didn’t like the sight of dapper suits and Commodore PET computers.)

Shelley reunited with Diggle (and occasionally other early members of the band) in 1989, playing once more as Buzzcocks. The group would eventually release another six studio albums over the years, most recently 2014's The Way, still embracing the muddy-but-cheerful guitar chords that once helped them define the pop-punk sound.

With his music, Shelley helped to distill the raw, naked emotion of punk into something that mopey teenagers could hook into, an ambassador from the musical rebellion to the hearts of kids it might not otherwise reach. “Yes, the world sucks,” his songs acknowledged, “But that doesn’t mean it can’t be fun, too.” (“Also, why won’t this person date me?”) Literate and lyrical, it never lost touch with the human side of rebellion, and the small joys a little melody can inject into the morass.