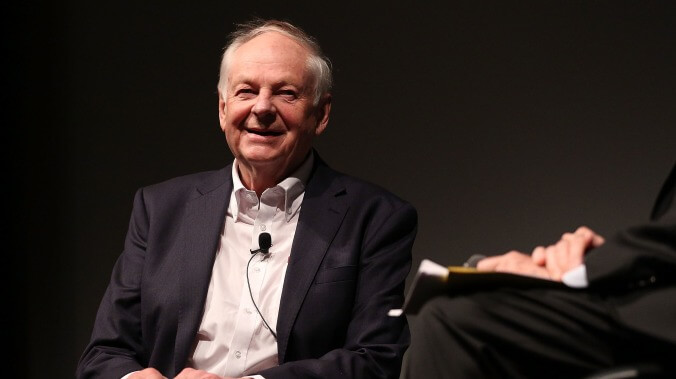

R.I.P. Richard Williams, Oscar-winning animator of Who Framed Roger Rabbit

Richard Williams, a three-time Oscar-winning animator whose creations breathed groundbreaking life into 1988's Who Framed Roger Rabbit, has died. Williams—despite the widespread success of his high-profile Disney project—was largely resistant to the lures of the Hollywood system, spending much of his career investing energies in independent projects—most notably his ill-fated opus The Thief And The Cobbler, which he worked on, in one form or another, for the better part of 31 years.

Born in Canada, Williams first came to widespread attention in 1958, when he won a BAFTA for his short film The Little Island. Surrealist, philosophical, and dialogue free, the movie centers on three men having visions of Truth, Beauty, and Good on an isolated island—which, in addition to their metaphysical connotations, also allowed Williams to show off a dizzying array of animated techniques. He’d add an Oscar to his pile of accolades in 1971, directing a TV version of A Christmas Carol (with Alistair Sim reprising his role as Scrooge) that was so beloved it ended up in an award-winning theatrical release.

(He wasn’t afraid of a bit of good old-fashioned kid-traumatizing, either; Williams also directed the Raggedy Ann & Andy movie, with eye-catchingly grotesque animation from folks like Emery Hawkins.)

But Williams’ most widelyacclaimed work came in ’88, when he took home two Oscars for his work on Roger Rabbit. (Something that must have rankled at least a bit, given that the fiercely independent Williams reportedly only consented to work on the Disney production so that he could secure more funding for Thief.) Working as the film’s animation director, opposite Robert Zemeckis, Williams’ animation helped bring Gary K. Wolf’s much darker and more bizarre novel to vibrant, irresistible life, tipping its hat to numerous legends of Golden Age animation in the process. Zemeckis has rightly been praised over the years for his ability to blend the film’s animated and live-action elements, but it was Williams and his team—and their note-perfect recreations of not just beloved cartoon characters, but the manic energy that empowered them—that made the magic so memorable.

Buoyed by the sudden bump to his reputation—and with a Special Achievement Academy Award under his belt—Williams was finally able to find funding for The Thief And The Cobbler, inspired several tales from The Arabian Nights. Gorgeously (and expensively) animated, the film was very much in Williams’ style: Light on dialogue, but heavy on a blend of old-school, Looney Tunes-esque animation and incredibly lush, jaw-dropping backgrounds. It was also slow to make and far over budget, which is why Warner Bros.—who’d agreed to pay for the film—eventually made the heart-breaking decision to take the movie Williams had been working on for much of his adult life away from him. (It didn’t help that Disney’s Aladdin was looming on the horizon.) Finished by Fred Calvert, the movie was eventually released in two truncated cuts, with Miramax releasing it Stateside as Arabian Knight (with a great deal of new, Jonathan Winters-voiced dialogue for the previously silent Thief.)

Williams never directed another feature. (He did lend his tacit support, though, when fan Garrett Gilchrist released a “restored” cut of The Thief And The Cobbler years later, working from his original storyboards and workprint.) Instead, he turned to teaching the craft of animation, including writing The Animator’s Survival Kit in the early 2000s, followed by an animated version of the book a few years later. (Although the book is widely praised for its notes on technique, it’s also been criticized for Williams’ often-retrograde views on sexual orientation and expression, including his half-joking assertion that gay men have a different walk cycle, and his tendency to focus on Jessica Rabbit-esque exaggerations of the female form.)

Like many of the most individualistic animators of his era, Williams never meshed well with the studio system, an outsider impulse that limited audience’s exposure to his work. But it also meant that when something did get through, it made you sit up and say, “Wow, I’ve never seen something like that”—even when he was taking some of the most recognizable cartoon characters of all time and letting them out to play.