R.I.P. Stanley Donen, co-director of Singin' In The Rain and legendary innovator of the Hollywood musical

Stanley Donen, a veteran Hollywood director whose career spawned possibly the most productive and innovative period in the history of the Hollywood musical, pushing the limits of the form with movies like Royal Wedding, Funny Face, and his celebrated (if emotionally fraught) collaborations with Gene Kelly, has died. Donen—one of the last greats of the Golden Age of Hollywood, honored in 1998 with an Honorary Academy Award “in appreciation of a body of work marked by grace, elegance, wit and visual innovation”—was 92.

Born in South Carolina, Donen got his start in show business as a Broadway dancer, serving as a member of the chorus line in musicals by the famed director George Abbot. (Donen was eventually fired as a dancer, but kept on in a behind-the scenes role, setting a precedent for much of his early career.) It was there that he met Kelly, 12 years his senior, and a rising star in the Broadway world. While the two men’s relationship would eventually break down into 40 years of passive aggression, public sniping, and bitter acrimony—it’s rarely a good sign for a creative partnership when one man marries the other’s recently divorced ex-wife—Kelly first served as a mentor for Donen, bringing him on as his personal choreographer. When they both ended up in Hollywood a few years later, the relationship would resume, producing some of the most innovative dance numbers in film history.

People have spent the better part of a century trying to tease out the exact nature of Kelly and Donen’s division of labor, with reports ranging from full mutual collaboration, to those who like to portray Donen as a glorified camera operator capturing Kelly’s genius. (A position that seems to miss the point that many of his and Kelly’s most beloved sequences are about the editing and the movement of the camera, as much as they are the fleetness of people’s feet.) For what it’s worth, Kelly would later credit Donen with the ideas for both the “dancing with his own reflection” sequence that helped make him a national star in Cover Girl, and the technically demanding “dancing with Jerry The Mouse” sequence from Anchors Aweigh. (Both men were aiming to snag Mickey Mouse instead, but such were the vagaries of the studio system.)

After proving themselves on the previous films, Kelly and Donen were given their own movies to co-direct, creating first On The Town—with its famous, shot-on-location rendition of “New York, New York”— and then the film that remains the pinnacle of both men’s careers, 1952's Singin’ In The Rain. Of the latter movie, it’s hard to find much to say that hasn’t already been said; presenting a loving satire of early Hollywood history, the film is that rare cinematic thing that’s capable of holding itself up proudly almost 70 years later, crystallizing Donen and Kelly’s ideas about the ways movies could transform and heighten the presentation of musical numbers beyond simple recreations of Broadway shows.

With his newly minted status as a successful Hollywood director under his belt, Donen continued to break out on his own, scoring a solo hit with his follow-up Seven Brides For Seven Brothers. But that success also laid the groundwork for the dissolution of his and Kelly’s partnership: When the two came back together for 1955's It’s Always Fair Weather, things started off tense on set and steadily got worse, as a freshly confident Donen pushed back against Kelly’s control. The film was a mild success, but the damage was done; see above, re: 40 years of bitter acrimony.

Donen spent five more years refining his tastes for the Hollywood musical—this is the period that produced Funny Face, The Pajama Game, and Damn Yankees!, all solid hits—while also establishing a new working partnership with established star Cary Grant. And while Donen’s break into independent production would see him suffer from the same cycle of periodic flops that hits pretty much anybody who makes that many movies, over that long a period of time—audiences reportedly did not enjoy his two collaborations with Yul Brynner—he also had a knack for knocking out the occasional massive hit just when he needed it. Take, for example, the ’67 Cook-Moore comedy Bedazzled, or his 1963 Hitchcock pastiche Charade, which became the most financially successful film of his career. (He and Audrey Hepburn were capable of some real magic together; see also their emotionally charged road movie, Two For The Road.)

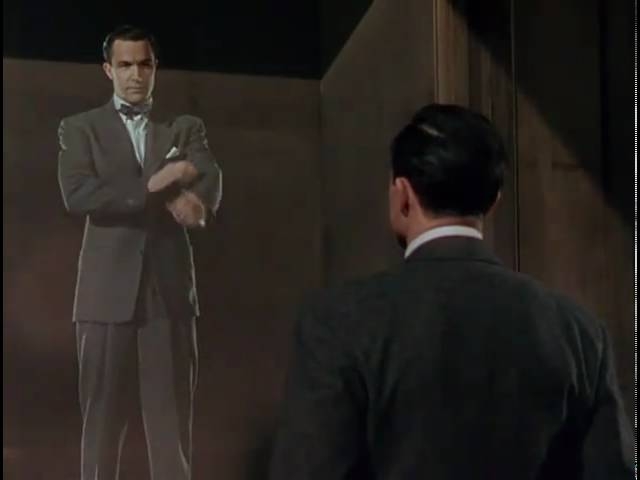

Donen’s career went into a prolonged decline in the 1970s and ’80s—his singular foray into the world of science fiction, the Kirk Douglas-fights-an-evil-robot thriller Saturn 3, was, well, not exactly Singin’ In The Rain—but he continued to develop projects, while also moving into a role as one of Hollywood’s elder statesmen. In fact, his most notable work from this later period—the video for Lionel Richie’s “Dancing On The Ceiling”—contained a number of references to his earlier work, including Fred Astaire’s famous “dancing on the wall” sequence from Royal Wedding.

Donen’s personal life was frequently messy—he and Kelly never reconciled, and he was married five times, with the relationships rarely ending on happy terms. (His final long-term romantic partner was legendary comedian Elaine May, who resolutely refused to become marriage number six.) But his legacy as a filmmaker is essentially impossible to argue with, not least because he came into the world of movie musicals at a pivotal point in Hollywood history: The moment, reflected in so many genres, when directors began to fully grasp that cinema freed them from the restrictions of merely recreating real-world moments, and could instead be used to tell stories in a way that no other medium could. Through deft editing, innovative camera tricks, and a dedication to bending audiences’ understanding of what movies could do, he not only helped define a movement, but laid the groundwork for decades of visual storytelling to come.

And he filmed a damn fine dance number, to boot.