Race’s history lessons don’t gather momentum

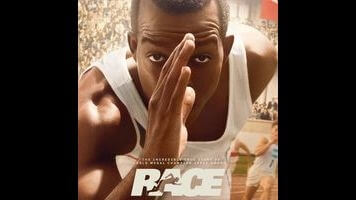

Race will probably be described as a biopic—and it sort of is one—but technically speaking, it does what a lot of filmed biographies refuse to do. Rather than tracing the life of Olympic athlete Jesse Owens from childhood to the grave, it follows him from his freshman year of college at Ohio State to his triumph at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. That is to say it covers a period of about two years, here compressed enough to feel like six or seven months, helping its 134-minute running time along. When he arrives at his new and sometimes-hostile school, Owens (Stephan James) is quickly recruited by track coach Larry Snyder (Jason Sudeikis), who has one eye on recapturing former Ohio State track glory—and the other on the upcoming Olympic trials.

Their partnership falls somewhere between typical mentor-protégé stuff and lightly mismatched buddy comedy (minus the laughs, for the most part). James, who has experience both with limited-scope biopics (having appeared in Selma) and student athletics (having spent a little time on Degrassi), is plenty likable, and while Sudeikis doesn’t alter his performance style much—his usual wide eyes, cocked eyebrows, and relentless hectoring remain intact—the eventual camaraderie between the two has enough snap to get by. Though a decent portion of their screen time is spent on the two men exchanging pithy callbacks to conversations they had earlier (and softening up some infidelity and possible alcoholism), the relationship between Owens and Snyder is nonetheless the heart of Race.

If this heart beats consistently but not robustly, it’s because despite its limited window, the movie splits the difference between intimate and epic. It gestures at the latter by cutting away from Owens and Snyder to explore the thorny business of negotiating an international event like the Olympics in an international climate like the one in 1936, with Germany ramping up its Hitler-led atrocities as other countries looked on with uncomfortable dismay. For these scenes, Race throws to veterans Jeremy Irons and William Hurt as, respectively, Avery Brundage and Jeremiah Mahoney, administrators on opposing sides of the debate over whether the U.S. should participate in the Berlin Olympics at all. There’s also a generally sympathetic side portrait of filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl (Carice Van Houten), who is busy making her other Nazi propaganda documentary, Olympia, but sees no reason to exclude Owens, to the chagrin of her employers.

The subplots have thematic resonance; the negotiations between the U.S. and Germany mirror the dilemma Owens faces over whether to represent his country or boycott the Olympics over Germany’s increasingly appalling treatment of Jews and blacks alike (and, for that matter, his home country’s lousy record with black citizens). But the film never yokes these threads together in a particularly compelling way. Mahoney disappears after a few scenes, and the morally ambiguous Brundage has only glancing contact with Owens. The movie converges on the stuff everyone can agree on: Hitler and Goebbels were monsters.

This leaves the athletic competitions to carry the film home. To this end, director Stephen Hopkins, whose ’90s CV makes him sort of a spare Renny Harlin, keeps things moving, but not sprinting; he doesn’t shoot the athletic action with much verve. Granted, track events present a substantial cinematic challenge; one Owens specialty, the 100-meter sprint, lasts in the vicinity of 10 seconds. But whenever Owens takes off, the camera cuts away, or lags behind, or renders the action a little fuzzy. It’s like Hopkins can’t stare straight at him.

There is one prolonged moment where the film’s concerns with history and personality come together for genuine visual expression. A lengthy moving shot of Owens walking into the Olympic stadium by himself, out of silhouette, into sunlight, and then under the passing shadow of a Nazi blimp (the period settings involve almost as much casual background CG as a comic-strip movie) before he takes his place at the starting line has more momentum than any of the actual races, or any of the scenes between Owens and his love Ruth (Shanice Banton). The rest of Race has other moments of engagement in a slickly produced and watchable package. But ultimately, it offers history told as a series of passing anecdotes.