Raise a butterbeer to Harry Potter, the most underrated of hit franchises

With Run The Series, The A.V. Club examines film franchises, studying how they change and evolve with each new installment.

The Harry Potter films are among the biggest money-makers in showbiz history, and in their own quiet way have been perhaps the most influential series of the early 21st century—at least in terms of the lessons Hollywood has learned from their success. So why aren’t they talked about more? Why aren’t the eight movies constantly on cable, the way the Marvel Cinematic Universe is? Where’s the bidding war between Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon for the streaming rights to one of the most binge-worthy of this era’s blockbuster franchises?

Maybe the problem is their perceived inevitability. Steven Spielberg reportedly turned down the opportunity to direct the first Harry Potter because he didn’t see it as any kind of challenge to make a pile of money off a guaranteed hit. His attitude has largely become the critics’. Though hardly disdained, to some extent the Potter pictures are looked on primarily as product. Cinephiles will sometimes point to the third chapter—Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azkaban—as the one most worth revisiting, because it was helmed by Alfonso Cuarón, a filmmaker with a strong sense of style. Otherwise, the movies are generally seen as equivalent to an audiobook, where any individual artistry is subordinate to the demands of novelist J.K. Rowling’s intricate plotting. The special effects teams and the star-studded supporting casts carry much of the load with the Potters. Everyone else’s main task was to stay out of the way of the source material, which already had millions of devoted fans worldwide.

But while these films are primarily feats of craftsmanship, they’re remarkably well-made. The Harry Potter series suffers from excessive faithfulness, which somewhat diminishes their value as cinema. But with one exception, none of the movies are a chore to sit through. And they all contain moments of wonder, humor, and heart to compensate for their more turgid passages. They effectively bring to life a richly imagined saga that feels even more resonant now than it did when Rowling wrote it. There’s every reason to expect that fantasy fans and young adults will be enjoying this franchise for decades to come, and not just out of habit.

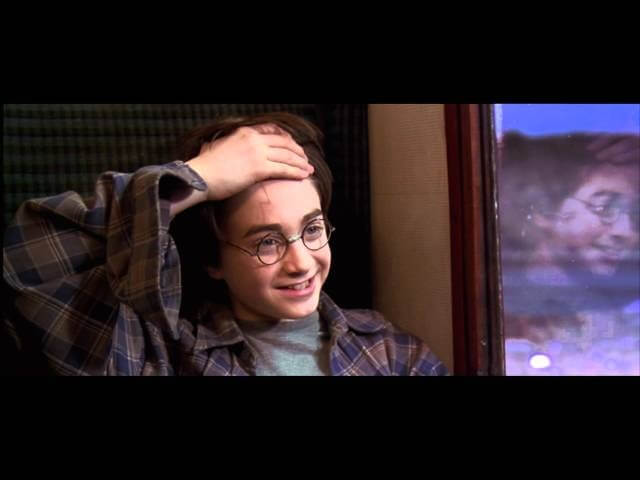

The reason for that is twofold: the page-turner quality of Rowling’s dense but carefully constructed character arcs, and a lot of luck in the casting phase. Nobody involved with planning out these movies could’ve known that young Daniel Radcliffe would grow into a handsome and talented adult, capable of carrying both the flawed humanity and heroic verve of Harry Potter—an orphan boy who wakes up one day to discover that he’s the budding wizard chosen by fate to keep a dark lord named Voldemort at bay. Few could’ve predicted that Emma Watson and Rupert Grint would mature so well as Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, Harry’s best friends at the Hogwarts boarding school where so much of the fight between good and evil takes place. And throughout the run, the producers were fortunate to enlist pretty much every accomplished British actor of the 20th century, including Alan Rickman as the complicated wizard Severus Snape, Maggie Smith as the benevolently officious Minerva McGonagall, Richard Harris (and later Michael Gambon) as Hogwarts’ powerful headmaster Albus Dumbledore, and Ralph Fiennes as Voldemort. These are—or were—all professionals, accustomed to giving even the most out-there characters and premises their all.

The movies’ middling reputation can probably be traced back to how the series began: with two Chris Columbus-directed chapters doggedly committed to recreating seemingly every scene from Rowling’s books. The producers wanted Spielberg. Rowling herself wanted Terry Gilliam. With Columbus, the series ended up with a perfectly competent, workmanlike steward, who deferred to Rowling and her preferred screenwriter, Steve Kloves. Their choice to cover as much of the novels as possible—including digressions and characters whose narrative function could’ve easily been redistributed—works just fine in Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone, where the episodic storytelling helps introduce “the wizarding world.” But the warts-and-all approach bogs down Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets, where the superfluous scenes offer either broad comedy or lead-footed action. In both cases, the films could best be described as “functional.”

That’s not to take anything away from Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone for non-Americans), which has the advantage of freshness, even now. Given what will happen later with both these characters and this story, the movie today generates sentimental pangs just about every five minutes, via everything from how young and innocent all the child actors look to how the overall tone is so bright and comedic. Much of the fun of the first film comes from seeing Rowling’s shadow-England come to life, with its hidden magical shopping malls and arcane histories, codes, and clans.

Sorcerer’s Stone also contains much of the kiddie-lit kitsch threaded through Rowling’s original novel, such as the corny reliance on classic “witch” and “wizard” iconography: the flying broomsticks, the magic wands, the pointy hats, et cetera. But perhaps because four of Rowling’s eventual seven Harry Potter books had already been published before Stone went into production, Columbus and Kloves knew enough about what was going to matter later in the story to emphasize small details about who flirts with whom and who might eventually ally with and against the hero. One advantage that these movies have had over other long-running franchises is that there’s no “back to the drawing board” at the start of each installment. They’re all important pieces of a larger whole. They all know where they’re headed.

Still, what keeps Sorcerer’s Stone from being in the top tier of Potter films is the same thing that makes it an effective introduction. It’s long, episodic, and choppily paced… almost like it was built to be watched in fits and starts on a minivan DVD player, or broken up by commercials on one long afternoon TV broadcast. That’s an even bigger issue with the punishingly longer Chamber Of Secrets, where a lot of the heavy lifting of the wizarding mythology begins. As Harry learns more about his parents, Voldemort, and the intertwined histories of Hogwarts and the magical realm’s “dark times,” the cheerier tone of Stone and the sheer joy of seeing people do spells and enchantments begins to fade. Kenneth Branagh has an enjoyable turn as a vain, self-promoting celebrity wizard, but the movie also introduces the house-elf Dobby and the bathroom-haunting Moaning Myrtle, both of whom have shticks that get tiresome quickly. In fact, a lot of the big set pieces in Chamber—a joyride in a flying car, a masquerade with the help of “polyjuice potion,” and a final fight against a serpentine “basilisk”—feel more forced and joyless than the ones in the first movie.

Perhaps that sense of premature exhaustion with Potter is what led Columbus to leave the series after only two movies. Whatever the reason, his choice makes it easier to divide these films into like-minded pairs. The first two are goofier and more kid-friendly. The next two are where accomplished directors take over, and start steering the franchise more toward classic fantasy.

The difference between Columbus and Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azkaban director Alfonso Cuarón is obvious within the first five minutes of movie number three. Cuarón just looks at everything differently. The framing and blocking isn’t as squared-up; there are more shots with characters at a distance, or arranged to create a feeling of depth. The actual color palette is darker and grayer, setting a precedent that would continue throughout the rest of the series. Azkaban is also the first film that required significant pruning of the source, because from here on out Rowling’s books are too long to adapt point-by-point. Yet Kloves and Cuarón keep enough of the scene-setting Hogwarts ephemera—the glasses of butterbeer at The Three Broomsticks, the whimsical candies, the fantastical feasts—to make it all feel genuinely magical again. And the filmmakers are blessed with one of Rowling’s more entertaining plots, featuring misunderstood villains, a tiny bit of time-travel, and a bigger role for Hermione.

Similarly, Kloves and Harry Potter And The Goblet Of Fire director Mike Newell get to work with what is arguably Rowling’s most enjoyable idea: a Triwizard Tournament that runs throughout the school year and brings young witches and wizards from all over the world to Hogwarts. In order to make room for the multiple long action sequences in the Tournament—not to mention the big Quidditch World Cup scene that opens the movie—Kloves and Newell skimp on a lot of the classroom material that had formed the spine of the earlier films. But they amp up the teen relationship drama, using a formal dance as a way to bring a lot of the regular characters together, forcing them to confront romantic feelings and resentments that have been bubbling up for years. Then, in a last minute twist, Goblet Of Fire brings back Voldemort, forcing Harry into his first prolonged confrontation with the Dark Lord who’ll be his primary nemesis for the rest of the series. There’s a reason why Rowling draws so much from the events in Goblet for her new play Harry Potter And The Cursed Child: This was one of her fullest, most satisfying stories, with long-term stakes and consequences, both big and small.

More importantly, Newell does the tale justice, visually. Cineastes often point to Cuarón’s chapter as the most aesthetically pleasing—which makes sense, given that it came right after his Y Tu Mamá También and right before Children Of Men and Gravity. Cuarón’s fine work on his Potter film fits right in with an amazing run. But while Newell doesn’t have the same reputation as a stylist, Goblet is actually full of more memorable grace notes than Azkaban. From the way the visiting ladies of Beauxbatons move through the Hogwarts halls in unison to the final lyrical shot of a ship descending beneath the river by the school, the fourth film is often downright poetic, in ways that have little to do with just serving the plot.

The next two installments—Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix and Harry Potter And The Half-Blood Prince—mark the arrival of David Yates, who’d become entrenched as the franchise’s permanent director. A virtual unknown to movie buffs before he got the Phoenix job, Yates had built his reputation with gritty, well-acted political melodramas on British television. His four Potter films are easily the darkest of the lot, with more muted scoring, and some jittery docu-realism in the action scenes. But his team’s excellent special effects keep a sense of wonder alive, even as the story becomes more grim and violent.

The biggest change with Order Of The Phoenix is a one-off vacation for Kloves, who’s replaced by screenwriter Michael Goldenberg. The new adapter shows a lot less of his predecessor’s fealty to Rowling’s text, and the result is a dramatically shorter running-time (especially given that the novel is the longest in the series), but also a movie that feels at times primarily like a plot-delivery device, with no time for personal lives or wizarding weirdness. It’s a pivotal film though, both because it tells a story where Harry really comes into his own as a hero, leading his peers, and because it introduces Dolores Umbridge, the franchise’s most fascinating villain. A sinister force who couches her evil in bureaucracy and smiley-faced condescension, Umbridge represents one of the major themes of this series: the idea that Voldemort’s return to power is facilitated not just by his “Death Eater” disciples, but by cautious politicians and weak-willed wizards and witches who’d rather stay on the sidelines and see who wins before they declare their allegiance. (That’s why, with the revival of fascist movements around the world, the Harry Potter story is starting to feel less and less like escapism and more and more like a warning.)

Kloves returns for Half-Blood Prince, and immediately pumps the running-time back up, at the expense of the pacing. The sixth movie is many fans’ favorite, and for good reason. It goes back to including more of everyday life at Hogwarts—right when the relationship drama is at its most intense—and it features both a thrilling quidditch match and the most memorable scene in the entire series, the climactic execution. But in retrospect, it might’ve been better for Yates and his writers to flip their approaches to chapters five and six. Prince is the film that’s really most about its plot, which has to do with Harry getting the final piece of the puzzle he needs to understand Voldemort’s plan. Until then, the gears grind slowly to get the story where it needs to go.

It’s tempting to lump the two parts of Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows together and judge them as one super-sized chapter, telling the tale of how Harry and his pals find all of Voldemort’s soul-containing “horcruxes” and then defeat him and his minions in a devastating battle at Hogwarts. But Yates and Kloves really do approach the two differently, with Part 1 functioning like an old-fashioned cross-country “hero’s quest” picture and Part 2 taking the form of a war movie. The split benefits Part 1, which has a different feel from any of the other films. It makes great use of everything Rowling had built into this world to that point, drawing on a diverse cast of characters and locations while also exploring how the dynamic between Harry, Ron, and Hermione had changed over the course of six years. If someone were to watch just Sorcerer’s Stone and Deathly Hallows: Part 1, the latter would seem like a sophisticated, visionary reimagining of a beloved children’s book—almost like a melancholy commentary on how the stories we tell to kids ill-prepare them for adult responsibility.

Part 2 is a disappointment by comparison, if only because so much of it is dedicated to long scenes of explosive warfare, in which the characters get a little lost. Even still, the second Deathly Hallows has some of the franchise’s most stirring moments: a daring heist at Gringotts Bank; Harry’s triumphant return to Hogwarts, with Professor McGonagall helping to lead all the students he’s inspired; the impressionistic flashback to Snape’s tangled history with Harry’s parents; and finally the tearjerking epilogue where the grown-up Potter and Weasley families send their offspring to school. As a movie in and of itself, Deathly Hallows: Part 2 is something of a slog. As a wrap for the series, it’s satisfyingly emotional.

Deathly Hallows: Part 2 rung up the highest grosses of any chapter, and at the time it was hard not to acknowledge how many people in the audience were college students or young adults. Both the books and the films bridged about a decade-plus in the lives of the kids who grew up in the ’90s and ’00s, shadowing their own maturation and giving them their own chance to look back at how far they’d come. The first movie hit multiplexes two months after 9/11. The last was released in the middle of President Obama’s first term. Over that decade, Hollywood embraced digital filmmaking, IMAX screens, and 3-D, all of which factored into the production of the Harry Potters. Yet the franchise remained remarkably consistent in look, tone, and intention, even as it turned darker. Few of the 10-year-olds who went to see Sorcerer’s Stone the day it debuted would’ve walked out of Deathly Hallows at age 20 and said, “This series has really lost it”—or even, “I guess I just outgrew this.”

None of these movies are masterpieces. Taken as a whole, though, they could well stand as the best sustained exercise in fantasy literature adaptation in Hollywood history. What would rival it? Maybe The Lord Of The Rings trilogy, if not for Peter Jackson’s compulsion to stretch rather than to compress. Perhaps some television series, provided that the likes of Game Of Thrones and Outlander finish strong. Fans of the MCU have a case, but the attempts to force all those films into a larger arc is often clumsy.

What will ultimately keep the Potter films popular—beyond the generations of new readers for the books—is that the nostalgia factor comes baked in. All the adults in these stories are constantly reflecting on their shared pasts, looking back at the times of camaraderie and conflict. And by the end of the last movie, the heroes have their own stories to tell, about both goofy misadventures and deep loss. There’s something powerful about seeing that happen right before our eyes. Over time, looking back at these films will be like staring at the ever-shifting portraits on the Hogwarts walls, seeing characters both frozen in time and constantly in transition.

Final ranking:

1. Harry Potter And The Goblet Of Fire (2005)

2. Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows: Part 1 (2010)

3. Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azkaban (2004)

4. Harry Potter And The Half-Blood Prince (2009)

5. Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone (2001)

6. Harry Potter And The Order Of The Phoenix (2007)

7. Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (2011)

8. Harry Potter And The Chamber Of Secrets (2002)