Ray Donovan: “The Bag Or The Bat”

Ray Donovan debuts tonight on Showtime at 10 p.m. Eastern.

Ray Donovan’s greatest flaw is its utter lack of ambition. Its second greatest flaw is that it possesses too much ambition, to the degree that it sometimes seems like it’s about to go flying off the edge of the Earth. There are good moments in every episode sent out to critics—five in total—but they’re not enough to overcome the crushing sameness of so much of what happens here, nor are they enough to overcome the sense that this show, ambitious as it is, has absolutely no center. Or, put another way, the best thing about the serialized TV drama in the post-Sopranos era is its ability to surprise. Think of any great drama from the last 14 years that you want, or even several dramas that were nearly great but didn’t quite manage the trick. All of them boasted surprising, shocking moments that, once revealed, seemed completely necessary for the characters and story after you thought about it for a second. Ray Donovan, at least as of yet, has none of that. It proceeds strictly to plan, right down to the obligatory fourth episode that takes the protagonist out of his element to underline how little he knows his own family.

At the center of Ray Donovan is the titular protagonist, a man from a working-class background in Boston who’s remade himself as a powerful Hollywood “fixer.” He’s the guy whom Los Angeles’ power elite call when they’re in a jam they simply can’t get out of, and he and his team swoop in to save the day. (In the opening moments of the pilot, that involves a famous actor who’s caught with a trans-woman, as well as another famous client who wakes up in bed with a dead woman. Ray’s solution to this seems novel until you realize that you probably just thought of it right now when thinking up possible situations yourself.) In such a pure expression of the Vocational Irony Narrative (a term coined by Hitfix’s Dan Fienberg to refer to stories about professionals who are unable to perform said profession on their own lives—the physician who cannot heal himself, etc.) that it seems vaguely insulting, Ray can fix anybody’s problems but his own. He’s got one complicated family at home and another represented by his father, released from a Massachusetts jail and headed to the West Coast to collect on some old debts.

At every level of Ray Donovan, it’s evident that talented people are working on the show. The list of directors seems like Showtime has unleashed the cable directing all stars on the proceedings, including three episodes from longtime HBO hand Allen Coulter and one from John Dahl, who’s done such great work over at FX in the past few years. The series’ creator and showrunner is Ann Biderman, an Emmy winner for her work on NYPD Blue and the woman who created Southland (though it should be said that her involvement in the series had decreased substantially once it finally took a turn toward the excellent), and just having a female showrunner’s perspective on the troubled man archetype that’s run through so many of the great series of the past decade and a half is refreshing, at least in spots. There are places where it seems evident that Biderman has no patience for Ray’s machismo or haunted expression, but they are, sadly, undercut by the places where she seems intent on underlining in red ink what a big, swingin’ dick this guy is. Still, if anyone is going to pull this show together, it’s Biderman, and this is definitely the sort of show that could take a while to find itself.

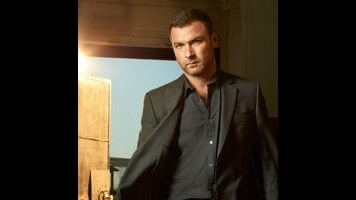

The strongest reason to watch the show is the cast, which is stocked to the gills with great actors. That starts with Ray himself, Liev Schreiber, who’s long been among the most mesmerizing thing onscreen in any of his films and repeats that performance here, in a role that has enough confidence in its leading man to let him be silent often. Paula Malcomson’s broad, broad Baaaaaah-ston accent feels too ridiculous too much of the time (to the degree that some sort of drinking game should spring up around it) in her role as Ray’s wife, Abby, particularly when one considers that Ray, also from South Boston, seems to have shed his accent just fine after years in the California sun, but Malcomson is always good, and when called on to emote, she acquits herself well. As Ray’s brothers, Dash Mihok, Pooch Hall, and especially Eddie Marsan all add layers of pathos to the proceedings, while Jon Voight is typically good (if underwritten) as the family’s patriarch. The show is so well cast that even smaller parts, like Ray’s co-workers, who all feel tossed into the proceedings at random, or his kids are played by actors who offer more than the usual cable glower.

So with all of these talented people involved in the show, what’s the problem? Quite frankly, Ray Donovan never suggests a good reason for its own existence, beyond the fact that shows with troubled, male, middle-aged heroes have been popular these last few years, so maybe there should be another one. There is not one thing that’s remarkable about Ray Donovan, the protagonist, to suggest that he should be at the center of his own television show. He feels so carefully constructed out of bits and pieces of other, better protagonists—a Don Draper here, a Tony Soprano there—that he ultimately comes across as a cipher, despite all of Schreiber’s best efforts to imbue him with gravitas. Instead of trying to make Ray interesting, the show relies on its supporting characters to do this for it, having so many instances of someone telling Ray how awesome he is (women want to sleep with him; men want to be him) that it feels like a frantic network note. “Are we sure people are going to like this guy?” that note might read. “We’d better have some of the characters keep talking about how awesome he is.” (Or, if we’re going the full Simpsons, like Homer Simpson’s notes for how to make Poochie a more beloved character.)

It’s not that the “woe is me; I’m a middle-aged white guy!” genre needs to disappear, not exactly. There are still plenty of vital variations on the form out there—including Mad Men and Breaking Bad, two of the best shows in TV history—but because so many shows in the wake of The Sopranos have used that basic character as the center of their storyline, there’s a higher burden on this genre to come up with some unique new twist or way of telling stories. At all turns, Ray Donovan feels so calculated and antiseptic as to suggest a show that was assembled via Mad Libs more than anything else. Ray hits for the troubled male protagonist cycle—distrustful wife, occasional bursts of violence, high-paying job that doesn’t ever pay quite enough—but he lacks any of Walter White’s unpredictability, of Don Draper’s pathos, of Tony Soprano’s psychological depth. At all times, Ray Donovan’s familiarity makes it feel, ultimately, unnecessary, and the show is constantly trying to overcome this by ladling on more overwrought emotion than the series is capable of bearing, via a frequently bombastic musical score or idiosyncratic filming choices that serve to highlight, rather than bear up, the mundaneness of the storytelling.

What’s more, as mentioned, Ray Donovan suffers from too much ambition in its premise to go along with the lack of ambition in its storytelling. There are something like seven shows running parallel to each other in nearly every episode. First, there’s the “case of the week,” where Ray has to clear up some sort of issue in Hollywood. Then, there’s whatever his brothers are up to that week, usually centered on the boxing gym where they hang out and work. Add into that Ray’s wife and kids’ storylines, as well as the serialized story of his father trying to avenge his imprisonment. Even beyond that, there are things like an unknown half-brother, another brother who suffered sexual abuse at the hands of a Catholic priest, a young woman who keeps throwing herself at Ray, and so much more. To be sure, Mad Men sustains this level of plot every week, but it also started out small and snowballed. Ray Donovan is trying to start out large and keep distracting us from how little thought it’s put into the center of the show. It’s no wonder, then, that the only episode sent out to critics that’s any good is the fourth, which mostly settles down and just tells a few stories about the characters in mostly isolated locales.

There are enough interesting things in Ray Donovan to keep watching—the Catholic sex abuse plot, for instance, is the sort of thing that serialized dramas haven’t really tackled just yet, while Marsan’s arc proves surprisingly moving and sweet—but the majority of the show strains for a profundity it has no idea how to attain. It is a show mistaking the artifice of complexity for actual complexity, the appearance of being intelligent for actual intelligence. At all times in watching it, I kept thinking of Shonda Rhimes’ daffily mad Scandal, which is surprisingly similar to this while swapping the gender and race of its protagonist and the coast on which it takes place. Scandal has no pretense of being “great” TV. It is unapologetically trashy and over-the-top and aimed at having fun first and foremost. But it’s also, at every single level, a better show than Ray Donovan, even operating under the constraints of network TV and the 22-episode season. It’s smarter. It’s better acted, written, and directed. It’s more in tune with the world we live in today. Ray Donovan has so many great people working on it in front of and behind the camera that it must have seemed like a home run from the word go. It’s a pity, then, that all involved forgot the lesson Scandal teaches week in and week out: Before you aim for making the best show on TV, it’s good to make sure you have a show at all and not just a collection of worn-out tropes.

Stray observations:

- There’s enough here to keep us interested—or just making fun of the show—that Sonia Saraiya will be in this space for the next 11 weeks to see if Biderman and company ever figure this shit out. I’ll be watching as well.

- For the record, my grades for the first five episodes would be C,C, C-, B, C+.