Read This: Pondering the unsolvable riddle that was Roald Dahl

The life of author Roald Dahl was a study in contradictions. While the mention of his name might give readers a warm feeling, Dahl’s long-suffering editors might feel differently. He was both a hero and a heel, by turns a devoted family man and an incorrigible philanderer. His spitefulness is legendary, as is his generosity. Meanwhile, Dahl’s record as a fighter pilot during World War II is admirable, depending on which account of it you believe, but the anti-Semitic comments he made privately still raise eyebrows. His work ranged from dark, unforgiving satire to gentle, uplifting whimsy. Even his heritage is a volatile mixture of British and Norwegian influences. So who was this man, really?

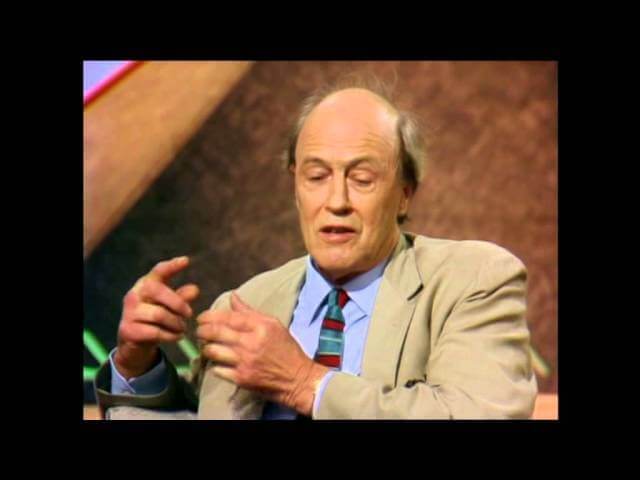

Jeremy Treglown, author of Roald Dahl: A Biography, attempts to present a comprehensive view of the Cardiff-born writer in a piece for Smithsonian entitled “The Fantastic Mr. Dahl.” In this context, the word “fantastic” is not necessarily an endorsement of the writer, but simply an indication that Dahl’s life was far out of the ordinary, marked as it was by triumph and tragedy. The nominal excuse for this article the release of The BFG, a new Dahl adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg. But stage and screen versions of Dahl’s work have continuously appeared on the market for decades, long after the writer’s death in 1990.

The Dahl who emerges from Treglown’s article is an utter enigma, though the biographer is ultimately sympathetic to his subject. The focal point of the article is a visit to the Roald Dahl Museum And Story Centre in the affluent English village of Great Missenden. The location of the museum is apt, Treglown points out, because it was Great Missenden and not Cardiff where Dahl did most of his writing. Much of that writing was done in a now-iconic shed that has become nearly as famous as its owner. Dahl, the article reveals, experienced more than his share of personal tragedies, and those experiences greatly influenced his writing. Charlie And The Chocolate Factory, for instance, appeared in 1964, as Dahl was still very much in mourning for his daughter Olivia. And Treglown suggests that Dahl’s later, gentler work, including The BFG, was made possible by his happy second marriage. The darkest passages of the article are those dealing with Dahl’s disastrously unhappy marriage to actress Patricia Neal, debilitated by strokes when she was only 40. Ultimately, though, this is a story of hope. Treglown ends his article with a discussion of the charitable work still being done in Dahl’s name today.