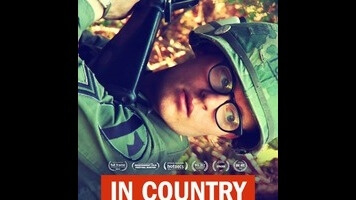

Real soldiers reenact the horrors of Vietnam in the documentary In Country

In Rambo: First Blood Part II, Sylvester Stallone’s embittered Special Forces operative is sent back to Vietnam on a top-secret mission. Upon learning of his assignment, he asks his commanding officer, “Sir, do we get to win this time?” It’s a question that resonates throughout the new documentary In Country, which profiles a group of men who painstakingly reenact an overseas skirmish from the late 1960s in the wilds of Oregon. Creeping through the greenery kitted out with period-authentic gear and weaponry, the men could be mistaken for mere weekend warriors if not for the fact that many are actual veterans of foreign wars spanning five decades from Southeast Asia to Afghanistan. This is military reenactment not as entertainment but as a strange form of catharsis.

The image of American soldiers wandering fully armed over home turf is suggestive, and In Country, which grew out of a short film by co-directors Mike Attie and Meghan O’ Hara, considers the implications of its subjects’ maneuvers without ever resorting to a detached or clinical gaze. For all the testosterone in the air—a rich musk of sweat and “bug juice” distilled from a 40-year-old, jungle-tested formula—the men are disarmingly thoughtful about their choice of extracurricular activities. In the interviews interspersed between scenes of vérité-style (faux) combat, they address the idea of confronting past trauma in a safe environment, or, in the cases of those without combat experience, the vicarious appeal of projecting themselves into somebody else’s nightmare. One man’s story is particularly powerful on this count: Vinh, an older South Vietnamese man who fought on the ground against the Viet Cong in the 1970s, speaks proudly of his history as a freedom fighter and takes palpable delight in ordering around the actors playing indigenous POWs.

In such moments, In Country is reminiscent of Werner Herzog’s 1997 documentary Little Dieter Needs To Fly, which put a former U.S. Army pilot through a simulation of his capture and imprisonment in Cambodia. The difference here is that Attie and O’Hara aren’t behind the elaborate re-creations that they’re filming. But there are moments of Herzogian strangeness, like the “death” and subsequent offhand resurrection of one of the participants, who gets to live out the masochistically heroic fantasy of being KIA and mourned by his comrades. The stickling for “authenticity” in every scenario is presented as an M.O. pitched halfway between a respect for the horrors of war and the micromanagement of men who yearn for a sense of control they simply don’t have in their day-to-day lives.

In addition to its obvious evocations of the past via the war games being played out for the camera, In Country gains a historical dimension through its deployment of archival footage of Vietnam, which effectively demonstrates the limits of even the most meticulous simulations. There are also enough enthusiastic references to classic war movies—most of them straight out of the mouths of the soldiers themselves—to hint that film and television don’t just reflect impressions of combat but shape them. It’s a different sort of campaign for hearts and minds, one whose most enthusiastic converts end up in the line of fire—or at least wish that they could be there to help the guys win this time.