In this case, the poor guy wading through his kitchen is Ah Tze (Chen Chao-jung), a petty thief who, along with best friend Ah Bing (Jen Chang-bin), spends his nights robbing pay phones and arcade games (they steal and resell the motherboards) and his days riding around Taipei on his motorbike. Ah Tze has also developed a crush on Ah Kuei (Wang Yu-wen), a young woman he’d previously overheard having sex with his brother/roommate. His desultory adventures are juxtaposed with the mostly silent longing of Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng), who’s supposed to be taking an intensive exam tutorial but becomes more interested in following Ah Tze around and spying on him. The narrative incident that connects the two storylines sees Ah Tze impulsively smash the side-view mirror of Hsiao-kang’s father’s taxi, but even that seems mostly random; Hsiao-kang eventually takes revenge, but his feeling of triumph is short-lived.

Every scene in Rebels Of The Neon God involving Hsiao-kang and his parents establishes a world that Tsai would go on to explore again and again. Lee plays essentially the same character in all of Tsai’s films (he always has the same name, at any rate, and there’s a certain amount of continuity from picture to picture); these two actors (Lu Yi-ching and Miao Tien) would continue to play Mom and Dad, respectively (and when Miao died in 2005, so did Hsiao-kang’s father in the movies); and the apartment seen here appears, virtually unchanged—even the rice cooker is in the exact same spot—in several later films. By contrast, Ah Tze’s romantic fumbling, which is more conventionally accessible, feels a tad perfunctory. Wisely, Tsai abandoned general teen anomie after Rebels, opting instead to double down on the weirder aspects of Hsiao-kang’s personality, which first surface here in a hilarious scene that sees him fake being possessed after overhearing Mom inform Dad that their son may be a reincarnation of the god Nezha.

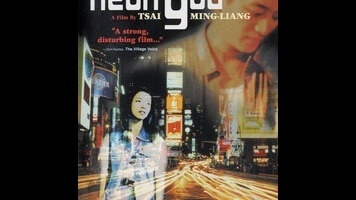

The titular neon god, however, is clearly Taipei itself. Tsai shoots the city lovingly, but he hasn’t yet developed the rigorous sense of composition that makes his subsequent films so striking; Rebels sometimes looks more like a clumsy version of the offhand naturalism that Jia Zhang-ke would turn into a fest-circuit trademark a decade later. The director’s deadpan humor is mostly absent, too (though that quality has vanished from his grim recent work—not a lot of laughs in Stray Dogs), and this film lacks the cathartic ending for which he now always strives. Consequently, it’s primarily of interest to longtime fans, or to those who think they might become fans and want to take this opportunity to start at the beginning. If nothing else, this is a rare case in which a director’s feature debut doubles as his greatest-hits album. To watch it is to simultaneously see where Tsai Ming-liang came from and precisely where he was headed.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.