It’s been more than 20 years since Alexei Kovalev became the first Russian-born player to have his name engraved on the Stanley Cup (apparently right above those of the other three Russians on the 1993-1994 New York Rangers), but a subtle prejudice against European athletes persists in the NHL. The word is usually “enigmatic”—that’s how sports writers assign an otherness to streaky stars like Alexander Semin, or underachieving dynamos like Alexander Ovechkin. This practice, however unconscious it may be, intrinsically underscores how politics can color everything they touch. And when it comes to the history of Russian hockey, that toxic influence is baldly transparent.

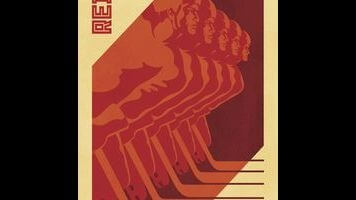

If Miracle can be thought of as Flags Of Our Fathers: On Ice, Red Army is its Letters From Iwo Jima. Gabe Polsky’s film humanizes the players of the Soviet Union national team, who were humiliated by a ragtag crew of amateur college kids during the most internationally politicized game in the history of American sports. Anchoring itself to the strange life story of the losing team’s captain, legendary defenseman Viacheslav “Slava” Fetisov, Red Army sprints through the history of Russian hockey in considerably less time than it takes to watch a single professional hockey game. With the charmingly combative Fetisov as a narrator, the film traces the NHL’s recent influx of Russian players way back to how Joseph Stalin—toward the end of his life—began to see the potential of his country’s obsession with hockey as a force for nationalistic pride.

Much of what Fetisov has to say about his experience on the Red Army team (and much of what Fetisov’s experiences on the team have to say about him) conforms to established stereotypes about the soullessness of Russia’s state-sponsored hockey system. But the film’s curiosity about the people who played for the Soviet’s national team naturally unearths a reservoir of humanity. It’s impossible not to sympathize with Fetisov and his former teammates as they recount the harsh conditions under which they were forced to live, confined to merciless training camps where they were denied the freedom to speak to their family members on a regular basis. Polsky’s approach drives a wedge between the athletes and the State: Once conveniently regarded as snarling goons, the players emerge as regular people suffering from universal wants, while tyrannical coach Viktor Tikhonov becomes a totem for the horrors of a disintegrating Communist state.

Red Army is most compelling when exploring the relationship between heritage and hockey. Polsky isn’t just interested in the effects of culture on sports, but also how those effects are manifest in the style with which they’re played. The way the Soviet team skated is the same way that current Russian players like Pavel Datsyuk do—in a silky, balletic manner, dependent upon teamwork to the point that a single pass can be ideologically expressive. Polsky’s film traces that style back to a single man, Anatoly Tarasov, and creates a fascinating parallel to the power dynamics at the heart of Soviet Russia: A single voice is disseminated through the synchronized actions of a workforce.

Unfortunately, Red Army never displays the same curiosity it’s sure to inspire. While it’s commendable that Polsky doesn’t mine easy drama from historical games that have already been covered to death, the speed at which he glosses over the Miracle On Ice and the 1984 Olympics epitomizes the film’s unwillingness to probe deeper into the moments that matter. Perhaps too concerned by hockey’s status as a second-tier sport in the U.S. (and the film is overtly pitched toward American audiences), Red Army relies on a hyperactive blitz of graphics and irrelevant archival footage to maintain a frenzy of interest. But the approach backfires, depriving the documentary of an appreciable pace and flattening the impact of its most incredible footage, such as the clips of Tarasov personally training Fetisov before the latter’s NHL debut. Nevertheless, it would be impossible to obscure the power of Fetisov’s wild life story as a hockey player and as a Russian, and his ultimate fate—readily available on his Wikipedia page, but best discovered in the final minutes of the film—helps Red Army resolve itself as a refreshing and open-ended look at the schism between politics and the people they shape.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.