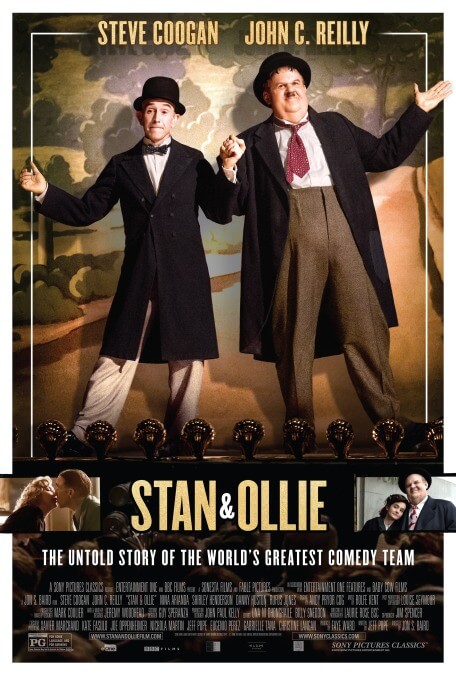

Reilly & Coogan make a good Laurel & Hardy in the otherwise unexceptional Stan & Ollie

Chronicling the slow, mournful fadeout of great artists: so hot right now. Just a couple of months after The Happy Prince, which focused on Oscar Wilde’s final years following his public disgrace, comes Stan & Ollie, the story of Laurel and Hardy as elderly borderline has-beens working the music-hall circuit. Apart from a brief prologue set in 1937, when the comedy duo were making Way Out West, the film ignores their glory days, preferring to watch them perform for half-empty houses and struggle in vain to finance a comeback movie. The tone here is bittersweet verging on maudlin, which is certainly preferable to TheHappy Prince’s wallow in pure misery. All the same, John Osborne’s play The Entertainer (adapted for the screen in 1960, with Laurence Olivier in the title role) previously covered much of this ground, using a fictional comedian. That approach, however, wouldn’t have provided an opportunity to see John C. Reilly and Steve Coogan mimic two of early cinema’s most iconic figures, which is this film’s true raison d’être.

They do a creditable job, though both actors, currently in their early 50s, are about a decade younger than were Laurel and Hardy in 1953, when the bulk of Stan & Ollie takes place. By that point, their film career was completely over (Jeff Pope’s screenplay fudges the chronology a bit by having them pursue a Robin Hood spoof that actually failed to happen in 1947, when they were still a bit more commercially viable), forcing them to take their act on the road across Europe. Discovering that their manager (Rufus Jones, hilariously unctuous) has booked them in shabby venues and put them up in fleabag hotels, Stan (Coogan) and Babe (Reilly)—as Hardy was known to friends—find themselves questioning their legacy, even as they continue to put all of their remaining energy into slapstick routines. A round of publicity stunts eventually attracts larger crowds, but also unearths lingering resentments dating back decades, to the period when perfectionist Stan wanted to break away from producer Hal Roach and easy-going Babe was reluctant to upset the applecart, even making one film solo when Laurel’s contract expired first.

Directed by Jon S. Baird (working in a much less frenetic mode here than he did in Filth), Stan & Ollie leans hard on the inherent pathos of past-their-prime legends, and Pope (who previously collaborated with Coogan on Philomena) generates conflict between Laurel and Hardy more or less at random, having one of them bring up a festering wound from their past whenever the movie needs a jolt of energy. Also on hand to help in that regard are Shirley Henderson and Nina Arianda, having a grand time as Babe and Stan’s respective wives, who despise each other—the former passive-aggressively, the latter aggressive-obnoxiously.

The film’s main attraction, though, is simply watching Reilly and Coogan replicate Laurel and Hardy’s classic comedy. Wearing a fat suit and a prosthetic double chin, Reilly mostly sounds like himself but captures Hardy’s key mannerisms, especially the slow-burn glare; he’s at his best when the two are onstage, showing how committed Hardy remained even when advancing age began to slow him even further down. (He died at 65, four years after the events depicted here.) Coogan, on the other hand, can’t quite manage Laurel’s daftly innocent look—his features are just too sharp—but digs into the star’s workaholic nature behind the scenes. Ultimately, there’s not much for fans to learn from Stan & Ollie, which skates blithely over the surface of the duo’s difficulties, and anyone unfamiliar with Laurel and Hardy would be better off enjoying the real thing in Sons Of The Desert or Way Out West. But celebrities playing other celebrities remains a popular pastime, and biopics have served up far worse than this.