Removing Kevin Spacey isn't the only way they could have improved All The Money In The World

Whatever else can be said about Ridley Scott’s ripped-from-the-headlines thriller All The Money In The World, you’d never guess—if you didn’t know already—that one of its key roles was occupied by an entirely different actor just six weeks ago. Gone is Kevin Spacey, who buried himself deeply under mounds of old-age makeup to play an octogenarian billionaire, but not deeply enough for anyone to forget the numerous sexual assault allegations recently made against him. Spacey’s completed performance has been replaced with a whole new one by Christopher Plummer, and whether Scott (expensively) reshot every pertinent scene or resorted to some Robert Zemeckis-style digital trickery, the substitution is seamless. Would it be faint praise to celebrate the director just for pulling off his 11th-hour (re)casting coup and still getting the movie to theaters by Christmas?

Plummer, who was actually Scott’s first choice for the role (and who requires no prosthetic work to look properly wizened), turns out to be the best thing about All The Money In The World. He’s stepped in to play J. Paul Getty, the real-life oil tycoon once known as “the richest man in the history of the world.” The film is set primarily in the summer of 1973, when a Roman crime syndicate snatched 16-year-old John Paul Getty III (Charlie Plummer, apparently no relation), not realizing that the boy’s wealthy industrialist grandfather had a hardline policy of not negotiating with kidnappers. Confronted by reporters, Getty flatly insists that he won’t shell out a dime, let alone the $17-million ransom, and we’re meant to recoil from this notorious tightwad, who falls somewhere between Ebenezer Scrooge and Montgomery Burns on the moneyed-bastard continuum. But Plummer, twinkle in his eye, can’t help but give Getty’s toxic rationalizations at least a ring of logic. If he pays out, won’t that just put the lives of all his other grandchildren at risk?

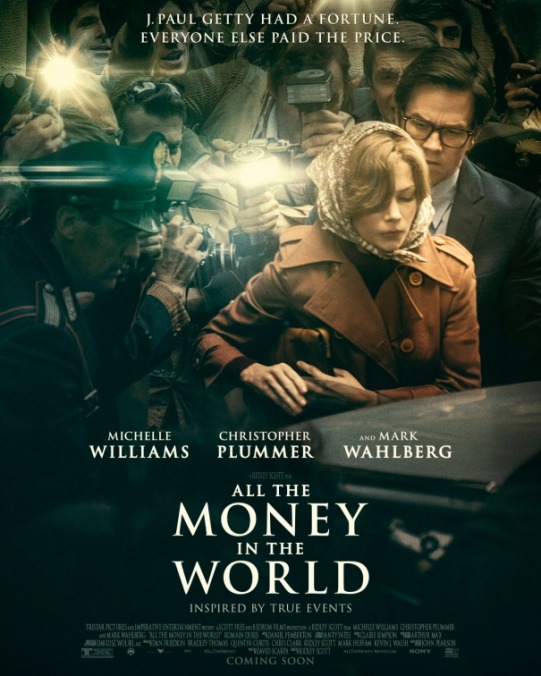

Adapted from a 1995 nonfiction book, All The Money In The World is uneven prestige pulp: a kidnapping drama that also fancies itself a study of how money corrupts relationships and short-circuits compassion. Much of the film is devoted to the battle between Getty Sr. and his daughter-in-law, Gail (Michelle Williams), who’s forced to negotiate not just with the men who have taken her son, but also the man who could arrange for his prompt return for only slightly more cash than what he regularly spends on rare artwork. This should be the emotional fulcrum of the movie, this tussle between the desperate, working-class mother and the pathological cheapskate emperor. But there’s not enough volatility in their showdowns, and Williams, speaking in what often sounds like a slightly shaky imitation of Katharine Hepburn’s famed Mid-Atlantic accent, never seems to connect with the full dread of her character’s ordeal. It doesn’t help that she’s playing a lot of her scenes against Mark Wahlberg, miscast as the ex-CIA operative Getty brings in to help frugally secure young John’s release. His character, Fletcher Chase, is supposed to be going through a slow-motion crisis of conscience, but as in too many of his dramatic turns, Wahlberg just sustains an air of vague irritation.

There’s more urgency in the scenes of the teenage John, alone and afraid in captivity, guarded by a petty criminal (Populaire’s Romain Duris) who slowly begins to see his prisoner as more than just a meal ticket. (It’s hardly accidental, the bitter irony that some goon-for-hire seems to care more about the kid than his own grandfather.) Not that this half of the film’s genre equation entirely works, either; the climax, which takes significant dramatic liberties with the true story, is faintly absurd, crosscutting as it does between an invented action set-piece and images of Getty alone in his mighty manor, like Charles Foster Kane. That’s not the only nod to the canon: The opening abduction scene begins as a brief homage to La Dolce Vita, complete with fountains, beautiful women, and the inviting nightlife of Via Veneto. And the 1970s timeframe allows Scott to throw another throwback, jukebox costume party, à la his American Gangster. Can we officially add “Time Of The Season” to the list of off-limits, played-out period establishers?

It takes a lot of control, talent, and experience to accomplish a last-minute retool like the one that got All The Money In The World into the world. But the truth is that Scott, who hasn’t made a truly great movie since the one-two punch of Alien and Blade Runner, can be proficient to a fault. His reliable, workmanlike approach—the professionalism that allows him to cut and paste actors out of a finished film and still make his deadline—doesn’t always suit messier material. To that end, some of the best moments in this version-2.0 thriller are the ones that traipse out of careful craftsmanship and into something wilder. There’s a scene, for example, that’s grotesque enough to have appeared in this year’s other Ridley Scott movie. Let’s just say Kevin Spacey isn’t All The Money In The World’s only excision.