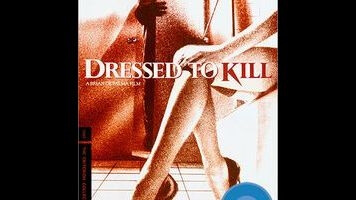

De Palma’s Dressed To Kill, which arrives on Criterion Blu-ray and DVD this week, features a schizophrenic psychiatrist as its villain. That counts as a spoiler, but it’s probably fair to say that the statute of limitations on surprises has run out after 35 years. Besides, it’s not as if the film really tries to disguise its big twist. No sooner have we met the prosperous Manhattan headshrinker Dr. Robert Elliott (Michael Caine) than De Palma’s camera calls attention to the little mirror sitting on his desk; it doesn’t take an advanced degree in psychology (or cinema studies) to detect the split personality symbolism.

Just as Dr. Elliott skillfully disguises his essential depravity underneath a veneer of intellectual respectability (and puts on a blond wig and a black trench coat when he’s on the prowl), Dressed To Kill is a giallo disguised as a metropolitan, mainstream thriller. It’s a film of impeccable pastel surfaces concealing a deep red, blood-drenched core. At this point, explaining the film’s relationship to Psycho is as prosaic and academic a task as, well, the psychiatrist’s explanation at the end of Pyscho—a scene De Palma gleefully parodies twice over in his final act. But it’s worth pointing out that where Hitchcock’s classic deconstructed Norman Bates’ psychological architecture as an afterthought, Dressed To Kill is explicit about duality at every level of its storytelling. Not only are its two most significant female characters, Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) and Liz Blake (Nancy Allen), inverted archetypes of one another—the bored housewife and the happy prostitute—but they keep trading places in literal and figurative contrast to Peter (Keith Gordon), Kate’s computer-whiz teenage son, who is himself a peeping-tom doppelgänger for De Palma.

As Chris Dumas explains in his recent and excellent book Un-American Psycho: Brian De Palma And The Political Invisible, Dressed To Kill was reviled upon its release. This can be seen as either a cumulative reaction to all the strategic hot-button-pushing its director had been doing in the previous decade (i.e., the menstrual overkill of Carrie) or as a byproduct of an increasingly conservative moment in American culture—a faux-modest swing to the right that De Palma was openly mocking in plot twists that directly linked sleeping around to violent death (Kate gets slashed up after tiptoeing away from a one-night stand). That coldly moralistic calculus predates Dressed To Kill, and even Psycho, and yet it’s hard to think of another comparably glossy studio movie—even from the halcyon days of New Hollywood—that goes so far in rubbing its characters’ (and its audiences’) faces in the idea that la petite mort is rooted in a murderous desire.

As usual with De Palma, it can be hard to inventory exactly which of Dressed To Kill’s most outrageous moments are evidence of a carefully calibrated absurdist sensibility and which ones out its creator as simply a feeble dramatist—a debate that rages on into the 21st century with films like Femme Fatale and Passion. Dressed To Kill doesn’t integrate its maker’s twin artistic personalities as a shockmeister and a satirist as neatly as its similarly Criterion-ratified successor, Blow Out. And yet it somehow feels more definitive as a document of what this particular director meant to film culture at the height of his infamy. It’s easy to see why people hated a movie as arch, violent, and glib as Dressed To Kill, and equally clear that this is exactly what De Palma was going for with all the gusto he could muster.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.