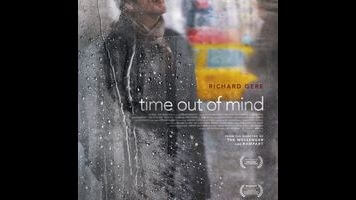

Richard Gere can’t quite convince as a homeless person in Time Out Of Mind

Richard Gere has always been more of a movie star than a great actor, and that’s partly because he’s spent most of his four decades in showbiz playing characters as comfortable and debonair as, well, Richard Gere. But in Time Out Of Mind, his atypical new starring vehicle, the aging Hollywood heartthrob does something he hasn’t done in ages, maybe since his breakthrough role in Terrence Malick’s Days Of Heaven: He plays a man of no means, with nothing to his name. When we first see his character, a vagrant named George, he’s sprawled out asleep in a bathtub, a makeshift bed in the abandoned apartment where he’s been squatting. George’s hair is an unkempt forest, his stubble patchy and gray. Around his eye is a trio of red lesions, evidence of some unspecified skirmish. We’re meant to be shocked by the way this stranger lives, in a there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I sort of way. But we also can’t help but look past George to the actor portraying him, and to marvel at how unglamorous this usually glamorous celebrity has made himself. It’s the epitome of the anti-vanity project—a way for a veteran charmer to prove that he has more to offer than charm.

Close to plotless, Time Out Of Mind is one of the most radically uncommercial projects Gere has ever been attached to. It’s equally adventurous for its writer-director, Oren Moverman, whose previous features, The Messenger and Rampart, were gritty and naturalistic, but otherwise fairly conventional, character-driven dramas. Here, Moverman is pursuing an unflinching, unromantic portrait of homelessness in New York City, which he achieves by subjecting his audience to the daily routines and hardships of his subject. The film isn’t nearly as good as its intentions, however, and that’s largely because Gere—for all his skip-the-tailor commitment to the role—seems capable neither of carrying two hours of emotional freight on his back alone, nor of entirely making us forget that we’re watching a swanky star dress down to play a person several miles below his station.

Most of the film is just Gere, who appears in every scene, stumbling around New York City in a haze of exhaustion, confusion, and intoxication, begging for change and searching for a place to crash. Hints and fragments of George’s backstory arrive at odd intervals, but never add up to a full picture; there’s no eureka moment, no crucial bit of exposition that explains how he ended up on the street. Occasionally, George spies on or tentatively approaches his twentysomething daughter (Jena Malone), who seems to have taken dad-resenting tips from Evan Rachel Wood’s character in The Wrestler. (What he did to lose her affection is never clarified, though a self-destructive weakness for the sauce could be the culprit.) He also befriends a chatty fellow derelict (Ben Vereen) who offers “attorney” services. Mostly, however, George is depicted as a man alone against the elements—natural, social, and bureaucratic. The film is most compelling at its most specific, offering a glimpse inside New York’s largest homeless shelter (a wing of Bellevue Hospital) and showing how difficult obtaining, say, a social security card can be when you have no job, residence, or identification.

Moverman films this stripped-bare material in unconventional and unintuitive ways, glimpsing Gere through windows, placing him against reflective surfaces (which occasionally creates expressive Wong Kar-Wai smears of color), and isolating him in lonely quadrants of the frame. The director shot many scenes using long lenses, mostly to capture him among the real hustle-and-bustle of New York, rather than surrounding the actor with an obtrusive camera crew. The result is close to the opposite of what Tsai Ming-liang achieved in his recent, similarly themed Stray Dogs: Whereas Tsai used the camera to force audiences to look long and hard at the type of people they usually willfully look away from, Moverman mimics the way many city-dwellers actually see the homeless—in quick, peripheral glances, often as part of the wallpaper of the city. The soundtrack, a din of crowd noise and random off-camera conversations, only enhances the sense that we’re watching someone who’s largely ignored by the world around him.

Artful and purposeful though this strategy is, it’s hard not to wonder if the material might be better suited by a starker aesthetic—one that would keep the focus squarely locked on George’s weary, weathered face. Then again, maybe Moverman knew the limitations of his star and figured it was better not to throw his performance under the microscope. Gere isn’t coasting here; he suffers, he cries, he never once leans on his tried-and-true charisma. But neither does he truly disappear into the part, into the desperation and despair of this broke and broken man. It’s always just Richard Gere up there on screen, and that, coupled with a number of distracting star cameos (by Steve Buscemi, by Kyra Sedgwick, by Michael K. Williams), works as an impediment to involvement. After a while, you’re just watching someone famous pretend to be someone invisible, in a film much easier to admire for its noble aims than its accomplishments.