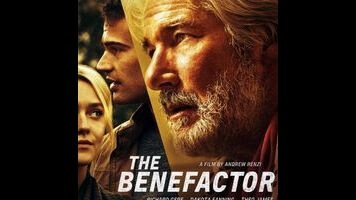

No amount of patchy facial hair or shabby attire could help typically dapper movie star Richard Gere convince as a man of no means, which is why the recent Time Out Of Mind, which cast him as a homeless person, never stopped feeling like an anti-vanity stunt. The Benefactor, his newest film, does better by the actor, if only by virtue of not asking him to play destitute. His character, Franny, whose name provided the film its original title when it premiered at Tribeca last spring, is about as wealthy as the man portraying him. But he’s also a mess, a desperate addict and leech who throws cash at his problems and tries to buy the affection of everyone around him. That makes the role well tailored to its occupant: Gere stays within his range of moneyed playboys, while still getting to indulge in the kind of unflattering behavior that a more put-together Richard Gere character would never exhibit.

Like roughly 80 percent of American independent movies, The Benefactor begins with a car crash. Five years after walking away from the accident that killed his married-couple best friends (Dylan Baker and Cheryl Hines), Franny lives a life of seclusion, holed up like Howard Hughes in his extravagant Philadelphia manor, his messy gray hair hanging down to his shoulders, his chin hidden beneath a bushy hermit beard. Then one day, he gets a call that snaps him out of his funk: Olivia (Dakota Fanning), the twentysomething daughter of his dead friends, is pregnant, married, and in need of some financial help.

Here the film seems to come to life, too. Franny, who owns a children’s hospital, doesn’t just secure a plum residency for Olivia’s new doctor hubby, Luke (Theo James). He also purchases her childhood home as a gift to the couple—the first of several acts of excessive generosity that come with more than a few strings attached. There’s something pushy and even a little creepy about Franny’s paternalism; he calls his surrogate daughter “Poodles,” a cloying nickname from when he used to dote on her as a girl, and constantly reminds “Lukey” who signs his checks and pays his mortgage. Writer-director Andrew Renzi is said to have drawn inspiration for this, his first feature, from the strange true story of John Du Pont, and the film outfoxes Foxcatcher in its depiction of a man who treats giving like a show of power—a way to exert control over those in his life. Gere, likewise, brings an edge of entitlement to the part, providing his character’s perpetual gregariousness the sour aftertaste of expectation.

If only the recipients/victims of this conditional support were more interesting. One problem with The Benefactor, for all the promise of its premise, is that neither of Franny’s foils are half as well developed as he is. Best known for playing the bland love interest of the Divergent movies, James lends Luke the embarrassed air of someone trying to decide when it’s okay to turn down a gift and how many hits to his pride he can endure in the name of gratitude. But there’s not much more to the character than perpetual discomfort. And his better half is even less defined: Olivia spends most of the movie either bashfully accepting compliments or sitting pregnant on the couch, waiting for her husband to call. Why hire Fanning, a gifted performer under the right circumstances, and then waste her presence on a nothing role?

For a while, it looks like The Benefactor might transform into a full-on psychodrama, taking Franny’s bullying nepotism into darker terrain. (The vague sexual undertones of his parental affection hint at an icky but interesting alternate direction.) But as a character study, The Benefactor is much more conventional and, well, charitable than it initially appears, especially in regards to its upshot: Rather than plumb the depths of Franny’s possessiveness, Renzi shifts focus to his pain-killer dependency, and suddenly we’re watching just another addiction drama, headlined by an actor given late license to indulge in lots of hysterical outbursts and fits of rock-bottom despair. Franny is simply more interesting as the antagonist, not the protagonist, of his own story. And Gere is more compelling when doing a nasty twist on the rich guys he typically plays than when pleading for our sympathy. That the film closes with a close shave is telling; it turns out as clean cut as its star, smoothing out the rough patches with the straight razor of boring catharsis.