The films of Richard Linklater, small miracles of humanism and ambivalence, ask simply, “How do we live? What does it mean? Where did it all go?” Many of them are to some extent about America—the leisurely national pastimes of baseball, conspiracy theory, and drugs—or at least Americans, usually southeast or central Texans in permanent-short-sleeves weather that the Austinite director’s latest, Last Flag Flying, deserts for the bleak, snow-shat winter of the eastern seaboard. The passage of time—or at a minimum, a hyperawareness of its fleeting—usually figures in there, too, as a natural hallucinogen that drips in slowly, kicks in hard. Early in Last Flag Flying, the grizzled, cigar-chewing ex-Marine Sal (Bryan Cranson) rasps, with an unpretending air that is the Linklater touch, “We were all something once. Now we’re something else.” A truism, maybe, but no one directs Americans musing about their own lives more convincingly than Linklater.

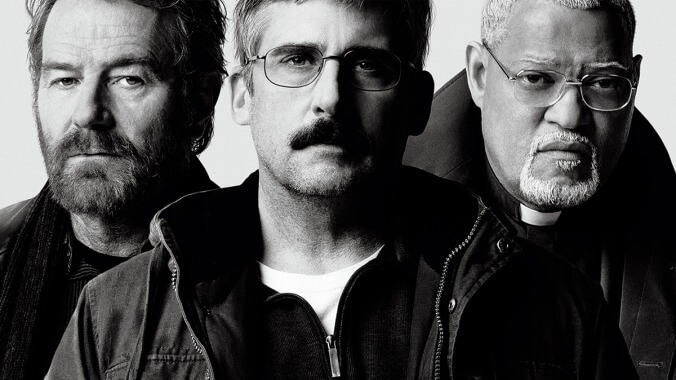

Last Flag Flying, which was adapted from a novel by Darryl Ponicsan, is actually one of his most conventional dramas; absent is the conceptual experimentation of the likes of Waking Life, Boyhood, Bernie, the Before trilogy, Slacker, and so on. One evening in late 2003, fifty-ish Larry Shepherd (Steve Carell, in wire frames and a mustache) walks into a Norfolk, Virginia, drinking hole owned by the aforementioned Sal, who’s too busy pontificating about the TV show Cops (it’s all fake, he says) to recognize this new customer as “Doc,” a buddy he hasn’t seen since the Vietnam War. The sequence is a minor, underplayed beauty, about as credible a depiction as possible of two men reuniting after 30 years. Gradually, we learn that the truth behind this visit: Larry’s son, Larry Jr., has been killed in action in Iraq, and he wants Sal and Richard “The Mauler” Mueller (Laurence Fishburne), a once hard-partying fellow vet who has since become a pastor, to come to the funeral.

Though the names and backstories have been changed, Last Flag Flying is a sequel of sorts to the 1973 classic The Last Detail, which was also based on a novel by Ponicsan; the characters played by Cranston, Carell, and Fishburne roughly correspond to the ones played by Jack Nicholson, Randy Quaid, and the late Otis Young in the Hal Ashby film. These echoes of the earlier movie create an additional layer of melancholy, though it’s not like this two-for-one bummer about the lies of Vietnam and the George W. Bush era really needs more elegiac qualities. Linklater’s atypically uncasual mise-en-scène brims with reminders of mortality, duty, and emptiness: uniforms, clerical clothes, motel rooms, a faded tattoo, an airplane hangar, a flag-draped coffin, the back of a rented box truck, snow.

Against the cold, Last Flag Flying hangs mellowly with its three main characters, pondering what meaning might be found in the apparent flimflam of patriotism and war. It’s all in keeping with the Linklater perspective on life: the running conversation that we pick up with different people or with years in between. One question leads to another, and the trip gets extended. Larry decides to bury his son in his hometown of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, instead of Arlington, transporting the body with the help of Mueller, Sal, and a young Marine chaperone (J. Quinton Johnson) who would otherwise be shipped back to Iraq. They guffaw through stories of their escapades. They visit the elderly mother (Cicely Tyson) of a comrade whose death has weighed on their collective conscience. They watch coverage of Saddam Hussein’s capture on TV. They buy cellphones. (Mueller’s obsession with “the minutes” is one of the funnier period-specific details.)

Perhaps the trio’s personalities are too limited (the crank, the sadsack, Rev. Jekyll), but the actors are terrific, with Carell doing his finest dramatic work as the meek Larry. But Linklater, for all his gifts in directing ruminative, digressive gab, isn’t exactly the king of dramatic structure. There are clumsy, didactic, and sentimental moments scattered through the film; at 124 minutes, it’s too long and episodic for its own good. But his sensibility—sympathetic, politically skeptical—strikes through at simple, important truths.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)