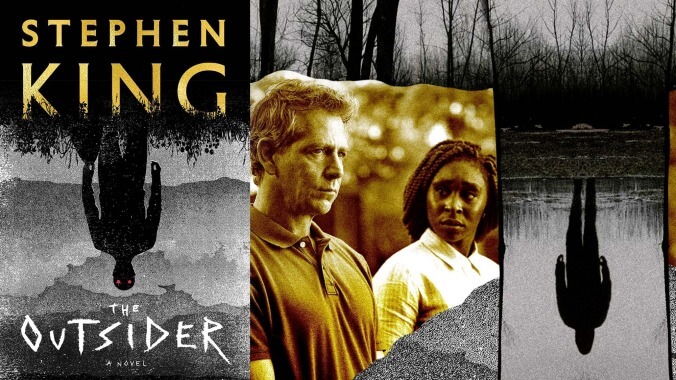

Graphic: Jimmy Hasse; Image: The Outsider book cover; Photos: HBO

There’s no existing TV series based on the work of Stephen King more reverent to its source material than HBO’s The Outsider. Hulu’s 11/22/63 and Mr. Mercedes deviated in ways that benefitted the originals, while duds like Under The Dome and The Mist did so in ways that showed just how little they trusted them. The Outsider, meanwhile, elaborates on King’s material in some ways—Holly (Cynthia Erivo) gets a love interest; Jack (Marc Menchaca) plays a larger, more interwoven role—but mostly sticks to the major beats, even as they play out differently than they do on the page.

So why is it that The Outsider feels so much less like a King adaptation than any of those other shows? The book, after all, is distinctly Kingian, with the author stamping his crime narrative with a folksy ensemble, oodles of myth, a fallible monster, and It-evoking themes that explore the ways adulthood hardens us to the unexplainable, even as the supernatural stares us right in the face. The series, though, is a different beast: Creator Richard Price (The Night Of) bends King’s story to his own aesthetic as a purveyor of hard-boiled crime; too far, one could argue (and some have).

As our recaps make clear, The Outsider is, by and large, a successful adaptation, but it’s not a stretch to say the front half towers over the second. Price excels at balancing the surplus of moving parts propelling its inciting narrative, which follows what looks to be the open-and-shut case of murdered pre-teen Frankie Peterson and Terry Maitland (Jason Bateman), the local coach whose DNA is all over the scene. Price, hewing close to King’s text, briskly walks us through the procedural elements of the case as he folds the confusion of the Maitlands in with the grief of the murdered boy’s family and the investigation of Georgia detective Ralph Anderson (Ben Mendelsohn), who boldly arrests his suspect during a public little league game, thus ensuring the latter’s status as a local pariah.

What’s missing is King’s warmth: The dialogue is terse, lacking in King’s amiable, detail-ridden monologues; the palette is gray and stormy; and the criminal justice system sterile, a far cry from the quirky small-town police stations of Castle Rock, Haven, and Derry. Price, a former writer for The Wire and longtime chronicler of inner-city crime, fortifies King’s book with the real-life terrors of prison, from the crowded cells and humiliating cavity searches to the hulking inmates whispering threats in the darkness. As we previously noted, all of it is scarier than the creature known as El Cuco. It’s a smart choice, giving authenticity and weight to a book that’s also at its best when it’s rooted in the real world. It’s also an intentional one; by hiring Price, HBO knew the series would emphasize the crime aspects of King’s novel over the horror. What they may not have expected, however, was for Price to layer even more grief into King’s story, which begins with the discovery of a child’s cannibalized corpse.

We’re speaking, of course, of the biggest change between Price’s The Outsider and King’s novel: the state of Derek Anderson, Ralph’s teenage son. In King’s book, he’s away at summer camp, occasionally recalled but never seen. In Price’s story, he’s dead, a victim of cancer. As Terry bleeds out on the concrete and the Petersons implode—be it through heart attacks, hangings, or gunshot wounds to the head—Ralph mourns. He and his wife, Jeannie (Mare Winningham), sit by their son’s grave. He stares blankly in a room filled with his son’s photos and trophies. He suffers memories of heavy drinking, drunken brawls, and marital strife. It’s almost too much—death on death on death—but it’s exactly what King’s story needed.

King’s got loads of great characters in his rearview—Jack Torrance, Randall Flagg, Annie Wilkes, all the It kids—but he’s also guilty of his fair share of boilerplate protagonists. Ben Mears, for example, is the least interesting part of ’Salem’s Lot, and the heroes of books like Under The Dome, 11/22/63, and Doctor Sleep aren’t all that much more interesting. Ralph, a happily married detective with a healthy son, a logical brain, and budding paunch, is one of them. In the series, however, nearly every aspect of his journey is informed by the fact that he lost his son to a faceless, uncaring disease shortly before the events of the series. His fury over Terry’s supposed crime is rooted in more than disgust and fear, but resentment, too—he knows what it’s like to lose a child, and to punish one child killer is to punish the very concept that children die. His grief blinds him, and his refusal to entertain the unexplained speaks to a cold, unflinching embrace of reality, one that’s fiercer and more emotional than it is in the book. His son is never coming back. His marriage will never be the same. His life will never be the same. And the world will continue to be cruel. (It helps, too, when you’ve got a heavyweight like Mendelsohn as your vessel.)

But then, in the closing moments of the show’s fifth episode, his son appears to him. “You have to let me go,” a spectral Derek says. It’s unclear whether the vision is a dream, an actual spirit, or a manifestation of El Cuco—if he can let his own grief go, perhaps he’ll give up his search for Frankie’s killer?—but it nevertheless triggers something in him he can’t quite articulate, or even process, until he sees Derek again, this time standing with Terry Maitland’s teenage shooter who he was forced to shoot and kill, in the cave with El Cuco. The many-faced monster continues to feed on his grief, just as his grief feeds on him, and, as Ralph comes to realize, “facts, evidence, [and] dumb cop shit like that” won’t help him overcome either. King’s book frequently dwells on humanity’s “natural disbelief”—a common theme in his work—but Price’s adaptation ties that concept directly into the vein of grief already coursing through the story.

Ralph’s ability, then, to finally embrace that which lies beyond his realm of perception carries a larger weight. His world has “cracked open,” and with it comes the understanding that losing someone doesn’t mean they’re gone. When he tells Jeannie that this vision of his son told him to let go, they laugh, because there is no letting it go. There is, however, space for a kind of grief that encompasses more than just pain. Maybe next time, he supposes, it’ll be “the real Derek.” Fuck, Jeannie posits, maybe they’ll see him in the afterlife. They both know there are crazier things in the world.

Start with: The book. It’s a quick, more exhaustive rundown of the story that will help you appreciate just how smart and balanced Price’s adaptation is. His take is better, ultimately, but only because he’s so good at honoring the original text while making clever narrative and thematic additions that elaborate on King’s text without corrupting it. To chase the series with the book will no doubt have you wondering why King didn’t make the choice to kill off Derek.