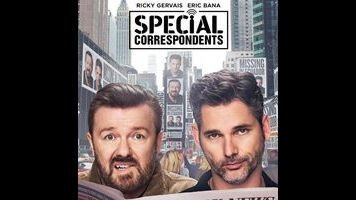

Gervais—who also wrote the script, adapted from a 2009 French comedy—stars as Ian Finch, a 50-year-old English expat who wears Dolby and Maxell T-shirts tucked in and is interested in little beyond radio and action figures. Eric Bana is Frank Bonneville, the leather-jacketed bad-boy star reporter at their low-rated all-news station, Q365 (“Twice as much news!”). A series of events too convoluted to get into here lead the two men to miss their opportunity to cover a potential civil war, so they enlist the dim-witted owners of a nearby restaurant (America Ferrera, Raúl Castillo) to help them lie low while filing bogus reports about roving paramilitary squads and a fictitious shadowy figure who goes by the conveniently common “Alvarez.” As Frank—and, by extension, the movie—puts it, the scam they’re pulling isn’t much worse that the deceptive theater of the big networks, where reporters don flak jackets to broadcast “ground-level” reports from an alley behind a hotel in Quito.

The more Special Correspondents skirts bad taste—by having the heroes record an ISIS-inspired ransom tape, for instance—the closer it gets to having something to say about mass media and geopolitics. Everybody wants in on the action, from Ian’s harpy soon-to-be-ex-wife, Eleanor (Vera Farmiga), who takes to the talk show circuit to promote a brazenly pandering charity single, to the separatist group that later takes credit for Ian and Frank’s abduction. But whatever point it might have is dulled by Gervais’ cursory direction and a shortage of real-world overlap. The internet seems to play no major role in this media landscape, though the men do at one point venture from their hiding place to buy magazines and newspapers. The choice of a stable South American country as a backdrop—Iraq in the French original—adds to the impression that Special Correspondents was pulled from the dregs of the 1980s. (Further contributing factor: The extended cocaine joke that is the movie’s third act.)

Maybe this would all matter less if Special Correspondents were funnier. Gervais does prickly and oblivious well, and his eye-rolling, dismissive “Oh, good, jazz” at the sound of a piano coming from a middle-of-nowhere bandit roadhouse makes for a rare offbeat joke in a movie of lazy gags. Playing ostensibly likable dorks, he tends to come off as strained; here he ends up getting upstaged by Bana’s take on the wannabe local celebrity and by Farmiga, Ferrera, and Castillo’s commitment to reductive caricature roles. And on his first feature without a co-director—after The Invention Of Lying and the little-seen Cemetery Junction, co-directed with regular comedy partner Stephen Merchant—the star comes across as something less than a natural filmmaker, relying on music montages and sudden leaps in time that kill any sense of pacing.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.