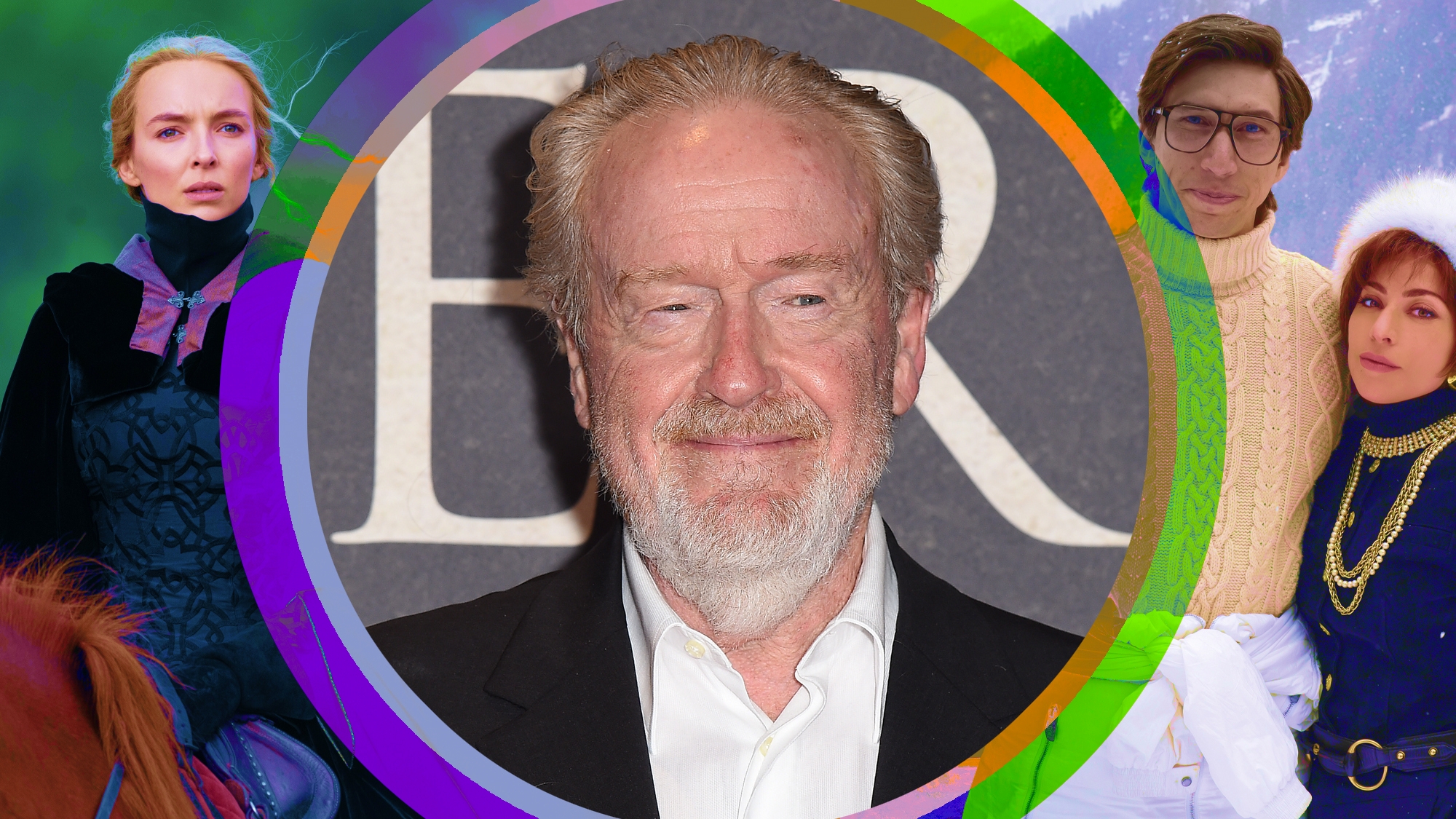

While he’s as prolific now at 83 as he was decades ago, Ridley Scott is still having somewhat of a banner year. He’s directed two high-profile films this year—The Last Duel and House Of Gucci—and he’s making headlines (again) for his brutal comments on the state of cinema today. We sat down with the legendary director to ask him about Adam Driver, his roiling work schedule, and the subjectivity of art.

I think what’s more important to me is that I’m allowed or they want me to continue working. Then, it’s all to do with “Have you got material that people want?” I have to come through the door with material because people stopped offering me films years ago because mostly I’m the hardest person to choose a subject for and therefore they don’t try. For the most part, I say, “Not really, but thank you for thinking of me for that,” if it gets to that.

Alien landed on my desk. I was fifth choice. The guy before me, bizarrely, was a great filmmaker called Robert Altman. But what on earth would you offer Robert Altman Alien for? He must have got to the breakfast scene and started thinking, “What??” But because of where I come from, which was fundamentally being a pretty good art director, I could see what I could do with it immediately. So I said, “I’ll do it.” So, you know, it’s horses for courses.

AVC: In House Of Gucci, there are some scenes that I really love that seem very real. For instance, there’s a scene in the bathtub with Lady Gaga and Adam Driver that seems spontaneous and natural and true. How do you create an environment on set to help actors work to their best potential?

RS: You make them work to their best potential.

AVC: Well, ask them to?

RS: No, I forced them to. It’s a big deal for me.

I’ve just gotten pretty good at casting. I don’t get into the medium-sized and smaller parts because I’ve got a lot going on when we’re going to do a movie. But I’ve almost always got in mind who will be the leading characters in the film. So when I’m reading it or preparing it, I’m preparing for so-and-so, so-and-so, and so-and-so on the basis that they’ll be the first bit we’ll go to.

So once I’ve got that in line and I get who I need to, the rest becomes forming a friendship and partnership with the actor. Because to me, I don’t believe in the Svengali process unless you’re casting a 6-year-old boy who’s never done anything before, and then you’re into trying to persuade this kid to do his thing.

With actors, you’ve cast great actors so that they don’t have to be stars. There’s a lot of great actors out there who are not stars. Once I’ve got a great actor, I tend to chat with them about anything but the script. I want to know who they are, how they think. I want to know how fast they are on their feet mentally because I’m pretty quick, and I want them to be able to evolve and grow with me on the set.

AVC: Do you consider yourself loyal to different actors, or do you just want the best actor for the role, period, no matter who it is?

RS: Well, I think you tend to go for who is best for the particular character. But I have worked with Russell Crowe five times and I’ve worked with Michael Fassbender four times, so it does happen where once you work with somebody and it’s A) got to be good fun. If it’s as if it’s a mountainous, difficult climb, forget it. You don’t want to go there again.

So, partly it’s how well you get on and how well does it evolve. The better you know somebody, the easier it is to say, “You know what? That wasn’t quite right. Can we do it this way?” So you have a real dialogue as opposed to a polite exchange. You need to get real and have a real dialogue pretty quick.

AVC: You’ve worked with Adam Driver two times this year alone.

RS: There you go.

AVC: What do you like about working with him and how did you develop that dialogue?

RS: Well, I was planning Gucci and I was making The Last Duel. I think Adam was literally trying on the chainmail and I said, “You know what, I’ve got a screenplay I want you to read this weekend.” He said, “What?” I said, “I’ve got this really interesting role. You may want to do it. I think you should read it.” And he read it that weekend and said, “Damn, okay.”

AVC: You caught him at just the right time. He had the right hole in his schedule.

RS: I overlap, otherwise, I’ve found you’ve got horrible gaps.

When you finish a movie—and everyone doesn’t do this same trick. You go find your own technique. But as I finish and I’ve said, “It’s a wrap,” I’ve been so inside that film for weeks or actually months. I’ve led my editor—and you’ve got to have a very good editor to do this. I trust the editor I have, Claire Simpson, totally. So she’s already cutting it and has been for the entire run of the movie.

I will then say, “How soon to a director’s cut?” She may say two weeks. Normally it’d be 14 weeks. She says, “I’m ready,” in three weeks, and I walk in. I’m really nervous because I’m now separated and fresh. I’m clear in my head. I’ve actually been working on something up until we sit down.

I have an assistant sitting next to me because once you start the screening, you cannot look away. If you go and write a note, that doesn’t work. You miss something. My films are organic, so I’ll just sit there watching, and calling out, “That! That! That! That!” and my assistant will be making a note of the number on the screen.

Then, after the screening, she’ll say, “So, you said something about the bathroom scene,” and I’ll say, “Oh, yeah.” I’ll give my critique on things that I saw because I’m fresh and [Claire’s] been editing. It is clearly less fresh and therefore to me, I’m coming in a bit like a computer. So far it seems to work quite well. But it means I can overlap one movie onto the next project.

AVC: I really loved The Last Duel, and I’ve been in rooms of women critics where they just rave about it, but we’ve also all talked about how, when we go look at most of the reviews, they’re written by men, and they didn’t like the movie or just didn’t see what we saw there. Have you experienced that?

RS: You know, everyone has a right to their opinion, and I realized that many, many, many, many, many years ago. There are many, many, many different layers. There’s a layer which I call the great unwashed, which is my favorite expression. It’s very rude and it’s fucking meant to be, because I don’t make movies for that lot.

I was, frankly, brutalized by a critic called Pauline Kael for a film called Blade Runner. Her review was systematically destructive and I had never met her. I didn’t meet her. She did four pages about it in The New Yorker, which is a very posh magazine. I was so in shock. I mean, it was a personal shock.

I framed those four pages and I have them hanging in my office today, and they remind me, with the greatest respect to journalists and critics, that I never read my own critique. When I’ve left the production, I have to have my opinion about what I did and I will move on.

If you get great critique, you think you’re walking on a cloud. If you get bad critique, you want to kill yourself. So it’s best to avoid both.

AVC: That brings me to another topic, then. You are well known for having strong opinions about all different kinds of movies. Do you think that taste is subjective? As in, are some things just not for you, or are there good movies and bad movies, full stop?

RS: No, there’s definite columns of intent. Studios will have a certain level of content that they will want because they think they’re going to be sure things. The thing they forget is there is no sure thing, but you can design a movie which will be sentimental, melodramatic, full of visual effects and no real story. And the visual effects support the fact there is no story. And so you, for the most part, are aiming at somebody who’s going to sit there with a giant bag of popcorn and Pepsi cola and watch it and not get what’s happening other than it’s noisy and it’s colorful and there are a great deal of visual effects.

Am I being rough?

AVC: No, but I do think sometimes you just want to go and watch stuff blow up.

RS: No, I never do and I never have done, even as a kid. I remember first seeing, and I think I was a teen, but I remember the first time I ever saw what I thought was quite a serious film. I think it was Orson Welles. He made it at 19 years old, Citizen Kane. I knew that right there, there was the difference and that’s who I wanted to be. David Lean, same thing. Occasionally you just see something and say, “That’s what I want to do.”

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.