Right now, even Frederick Wiseman shouldn’t get away with an apolitical look at small-town America

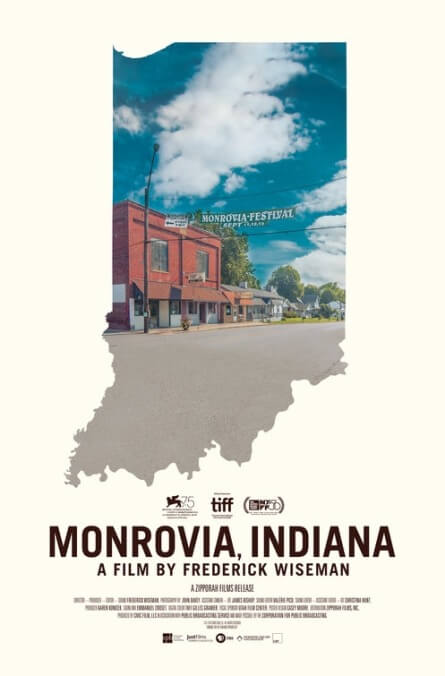

A few years ago, legendary documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman made one of his occasional geographical portraits, capturing an entire community rather than focusing intently on how one of its institutions works (or doesn’t work). In Jackson Heights had a lot of ground to cover, as that particular Queens neighborhood ranks among America’s most ethnically and culturally diverse; if you didn’t know better, you’d think that consecutive locations were separated by many miles rather than just a few blocks. As if to provide balance, Wiseman has now trained his studiously impassive camera on a much more monolithic area: Monrovia, Indiana, with a population of less than 2,000 that, according to the most recent decennial census, is 97.3 percent white. It’s in a county that Trump won by 56 points. Such details aren’t addressed in the film itself—that’s not Wiseman’s style, to put it mildly. All the same, his decision to explore this town at this moment doesn’t seem without purpose. And in the context of what’s currently happening in America, the film’s avoidance of politics itself feels political, in a maddeningly evasive way.

Even if one chooses to ignore that, though, Monrovia doesn’t rank among Wiseman’s best work, or even among his best recent work. Nobody’s conception of small-town American life will be challenged or upended (though some viewers have been deeply upset by a sequence that shows a vet amputating a dog’s tail, either because it’s graphic or because they assume—without any onscreen evidence—that the surgery is unnecessary). Much of what Wiseman captures here is so resolutely ordinary that it threatens to cross the line into outright dull. He devotes several minutes each to a wedding and a eulogy that offer little of interest to anyone not personally acquainted with the happy couple or the deceased. A Freemasons ritual honoring an octogenarian member goes on for what seems like a small eternity. (It’s like a Roy Andersson sequence minus the striking set design and black comedy.) Recurring city council meetings occasionally provide a shot of energy—one no-nonsense resident gives a remarkably passionate speech about Monrovia’s inadequate fire hydrants—but even those involve a lot of banal bureaucracy.

Then again, one could argue that the banality is precisely the point. Apart from a few quick, uninflected images, like shots of right-wing T-shirts and bumper stickers for sale at a local fall festival, Monrovia avoids anything that could be construed as divisive. Wiseman doesn’t conduct interviews, and people rarely launch into political diatribes unless prompted, so it’s not surprising that Trump and his agenda go almost entirely unmentioned; the closest the film comes to pointed commentary is one councilperson’s repeated, carefully vague expression of concern about impending demographic change. Mostly, it just presents the people of Monrovia, going about their business, living their unremarkable lives. Five years ago, that might simply have been a bit boring. Right now, it plays like the apolitical equivalent of those newspaper articles that sit down with Trump voters in a diner, seeking to understand what makes them tick. Wiseman has made the same documentary that he always makes (in his geographical mode), employing the same methods. Whether those methods serve him or his viewers well, in this case, is the crucial question.